Speaking to the creator of one of last year's best and most difficult games, The Banished Vault

"Some people just find it easy."

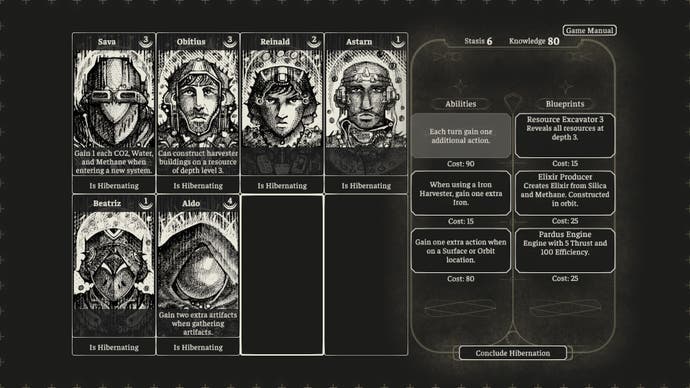

The Banished Vault was one of last year's best, and possibly most difficult, games. It cast you as one of the last Exiles in space - a kind of monk - and tasked you with outrunning a universe-swallowing darkness known as the Gloom. But underneath, it was a game about maths. A game about careful space flight and fuel economy, and about planning many steps in advance to execute a plan. Run at it with the expectation of easy progress and you will meet with an abrupt thump. It wasn't a game for everyone. But the people who persevered, loved it. Chris Tapsell called it "dense and brilliant, like a neutron star" in his Banished Vault review. "When it all clicks, and the fog of numbers and tables and energy calculators clears, it's magic."

To celebrate that a bit, I decided to track down the game's creator, Nic Tringali, for a chat. I ask them how life has been since the game came out, how people respond to it, and what they're working on now. I also arranged a Banished Vault key giveaway for yearly supporters of Eurogamer in the hope I can entice more people to play it.

Let's begin.

Eurogamer: I want to jump back in time a bit and talk about where the idea itself came from. It's quite a unique concept. Was this something you had buzzing around in your head for a while? Where did it come from?

Nic Tringali: It came together in fits and starts. The very beginning was: okay, can we make a game about the puzzle of rocket flight and fuel efficiency? In my head, I already knew how the game would look, in the kind of gridded planets and tree structure, because that's very easy to do procedurally. And that stayed on its own for a bit.

I imagine it was quite a dry presentation in terms of people seeing it and being excited about it.

Yeah. From the beginning it was like, 'Okay this definitely needs something to it - it can't be just like a pure numerical puzzle kind of thing.' Then at some point I realised... What I call the corporate horror space of Alien and Dead Space, which I love to be clear - Alien is my favourite movie so this is not a diss on those - but we've seen a lot of that, so I didn't want to do that. But what's the alternative? Because I didn't really want to stick to the extreme realism kind of thing. Even though a lot of the numbers and equations in the game are realistic, they're always going to be too abstract to be correct. On a spectrum of like NASA software to, I don't know, Asteroids the arcade game: this is like halfway between those two extremes. Kerbal was at 90 percent of NASA. But the closer you get to that, the harder it is to design, and the harder it is to have fun with it. So it's easier to simplify things. So I didn't want to do realism.

Then we just stumbled on Gothic architecture-

How did you stumble on that?

I think the catalyst was the wide shot in Alien of the ship with the spires [the opening wide shot of the USCSS Nostromo, I think]. It is very much a Gothic cathedral, and we were like, 'Wow, why don't we just- Instead of implying that it's Gothic architecture, let's just literally put a church in space.'

We were also thinking thematically. A lot of this was design-led from a point of view of you're never going to have a population of thousands to deal with. It was always going to be that two-to-eight number, just because from a player's point of view, that's easier as far as organising how many actions someone can do in a turn. So it couldn't be a generational ship where there's thousands of people. But you still want big spaceships. And then the loneliness, too, and the idea that these cathedrals are huge and take generations to build. Then everything starts falling into place. If in real life a Gothic cathedral took 150 years to build, that is thematically equivalent to going on a spaceship and going to the stars, which would take generations to do. Then from there, every visual element of the game was accounted for.

The map: oh let's go look at medieval manuscripts and inlays of churches and filigree. The spaceships: churches and spires and stuff. And the UI will look like it's etched stone. So it was about finding a theme that hit all the marks. We went through a couple of different combinations of things and this felt right and good and interesting, which is half of the battle, because you want to keep yourself interested in it.

Did The Banished Vault always have a board game approach?

Yes. Yeah that was in from the very beginning. And that goes back to the abstraction - like, I don't want it to be too realistic. And I like board games, and I like board game design. So it was like how much can I do with this and still have the entire game in the player's head? Because the main difference between board games and video games, obviously, is the players execute the rules of a board game, so they have to have the whole game in their head and process it. So it was a matter of how can we do that effect but in a computer game instead?

I have to ask: did you ever think about making it into an actual board game?

No, not really. I mean it probably could be if given the opportunity, and there are board games that do fairly realistic spaceflight. But it would also be tricky to do certain things like energy calculation, which is fairly complicated - logarithmic equations. If I can get the calculator mechanically working in real-life, then I'll make it. That would be the prerequisite, probably.

Speaking of mechanical things: another way in which The Banished Vault stood out was for having a manual in the game, and then a physical version accompanying it. When did that idea come up?

Really early - it's just something I was thinking about for a long time. And similarly, from the beginning, we knew how hard it would be to teach people the game. A manual, if done right, can actually be extremely effective. There's a lot of different reasons why.

One, from a production point of view, tutorials are very hard to make.

Oh, why's that?

Because a tutorial is constantly interrupting the normal flow of the game. If you imagine you're playing Civ and you take your action, do your thing and build your city, the tutorial has to stop everything, point out something on the screen and go, 'Why don't you do this three times?' But the game otherwise doesn't care if you do that three times. So yeah, they're quite time consuming and technically challenging.

And they have to be done at the end of the production, because your game is not really anything until the last however many percent, and then it's hard to iterate on it because you're running out of time. So from the production side, I was like, 'Well if we can do a manual, it's just the document I can write throughout.' The manual was started three months in and was consistently iterated and updated.

Then from a player-learning point of view, I think it's just easier to read a page of text. If you imagine every paragraph of the manual was on a little page on the screen and you've got to press 'next' and read three sentences at a time: it's harder to process that information as opposed to just going, 'Here's a page of text that has five paragraphs on it and a little bit of art.' And yes it's 50 pages long, which is a lot, but you can flip back and forth, you can skim ahead.

I had to do a lot of convincing on the team to be like, 'Trust me, I think this will work.' And it thankfully, did.

When did you decide the manual was also going to be a physical thing? Because I love that. It's very old-school.

Oh that was also from the initial pitch. And we were like, if it's an actually laid-out book we could just print it. Yeah, that was super-easy. So it was always set up to be printed from the beginning. That then informed the art decisions later on.

Did many people buy it? Because it's sold separately isn't it?

This is an older stat from late last year but it was 10 percent or something like that - of people who bought the game getting the manual. That was way higher than our expectations. We were thinking a handful of people would buy it as a fun little thing, and otherwise not bother, so yeah, 10 percent was really good.

We're about a year on from the release of The Banished Vault now. Do you remember how you were feeling back then, at the time?

Let's see. Every element of the game was in and we were essentially balancing it and playing it. And it was peak "I don't know if this is gonna go well". I mean, the whole production was like, "this is a really weird thing". It's very hard, but it's not hard in the sense that it's hard to do things. Typical game difficulty is like: play a guitar hero song on the next difficulty and your fingers are in your way. So it's easy to do what you want, but then the difficulty is figuring out everything you have to do. The balancing was like, "okay, that's the game - we can't take that out. But how do we get people on board with what that's doing?" So it was a lot of figuring out, okay, what are the difficulty levels? How generous do we want to be?

My expectations were confirmed when the actual game was out. Some people just find it easy. It works with their brain. It's one of the things that - and I definitely saw this in reviews, both player and critics reviews - if this game doesn't work with your brain, you hate it, right? And that's fine. And some people were on the complete other side of that like, "Oh, yeah, you just calculate the numbers and then execute on your plan."

So the run-up was: how do we find the middle point? Because if it's too easy, then everyone feels like it's too easy and there's not a game here, and if it's too hard, then obviously it's just impossible, except for the 10 people that turned around and were like, "it can be harder".

Have you had any interesting feedback from players about it in that sense?

The main feedback is either it's too hard or too easy. And that's fine. If everyone is on a big bell curve, you'll have people on either end of it. But otherwise, no, I think the main bit of feedback is, 'Oh, I understand this is supposed to be a frustrating or mentally taxing experience.'

So how was the launch period for you, now that you've had a bit of time to reflect, and how has life been since?

Launch was good. Launch was a very nice surprise in that most people actually did understand what we were going for. That's the validating thing. People liking it is obviously good, but people sitting down and going, 'Oh, okay, this is hard because going to space is a miserable experience by all accounts... It is this existentially difficult thing where one mistake...' The whole point of the game being hard is that you make the one mistake that ends the run and that reflects real space travel. So that was good. And then we already had a plan for adding a couple things after launch and then transitioning to a new project, which has essentially gone all to plan, which is very nice.

How did it do in terms of meeting your commercial expectations - has it been a success?

It is because our expectations were very conservative, and everything we planned in the run-up to launch was trying to communicate exactly what the game was, so people could look at it and go, 'Oh, this is not for me - I'm not going to enjoy this,' which is fine. Then conversely, if you see it and you see a calculator calculating real equations and you go, 'That's what I want,' then you're in. And we knew that that pool of people was not very large. But the team is extremely small, and so for us it was a successful launch because we didn't need to sell many.

It was largely made by you, I think?

Yes, with 2D art by garin - they're really good. Some of the 3D art was done by me and another member on the team, and then obviously producer and marketing and everybody getting everything rolling for the launch itself. But as far as designing and programming and everything, it was just me the whole time.

You mentioned transitioning to a new project: I saw you tweet about taking a prototype of it to the Game Developers Conference earlier this year. What is it - can you say anything about it?

The prototype was only started in December and so it's very, very, very early, but it was a good trip. But yeah, it's ridiculously early for that thing.

Is it quite different to The Banished Vault?

Yeah, I think so. I don't think it will be a surprising thing - it's not going to be a music game or something completely 180 degrees. But it's not going to be more of that, mostly because I just needed a mental break from putting my own mental paces through the wringer trying to play and test the Banished Vault as well. That was the main thing I needed a break from, so to speak.

And how do you feel looking back on the Banished Vault with a bit of perspective now? Is it all quite far away now you're working on something else, or are there things you wish you'd done with it but didn't? How does it sit in your mind?

No, I feel really good about it, honestly. There's certain projects I've been on, or even little side projects I've made, where you start out and you don't know where it's going to end up. It ends up somewhere you couldn't have predicted at all. With The Banished Vault, I couldn't have predicted it being a success like this, but I look at the finished game and I go, that's quite close to what I set out to do. And that's quite a nice feeling.

I think it helps seeing the people who play it, and understand it, are getting the experience that I intended for in my head, which is the ultimate goal of making games - especially for something that is not inherently pleasurable or fun. It's fun in the totality but moment to moment, it's quite frustrating or difficult. So seeing people engage with that and understand that at the end, you have the cathartic experience of completing it - that's good.

A big thank you to Nic Tringali for both a wonderful game and this interview, and to Bithell Games for organising it.