Starfield review - a game about exploration, without exploration

Liminal space.

Starfield does not begin well. You start this game of space and exploration in an elevator, trundling down through walls of rock to a subterranean mining tunnel. In this one early place Bethesda always likes to keep things tightly coordinated, characters delivering their programmed line of dialogue to you without looking up from their job as rock-shooter and drill-watcher. It's all so precisely on cue, as you walk by, that they feel a little like animatronics on a Disneyland dark ride, the echoes of that same line faintly echoing down the corridor as the next tour boat bobs along past Captain Jack Sparrow.

Your tour guide, mining supervisor Lin, eventually leads you to a deeper tunnel, where you're told a little bluntly to go and pick up something giving off a weird gravitational signal from the deep. This is an Artifact, a mysterious lump of scrap metal, and it teleports you, via seizure-slash-religious-experience, to the character creator.

Clunky as it sounds, absolutely none of this stuff is a problem. In fact really, it's actually classic Bethesda, and much as I'm being a little harsh about the cave puppets' patter I am more than on board with this part: it's the run-up to arguably the best moment of any Bethesda RPG, the "walkout moment", where our typically wordless chosen one begins somewhere dark and claustrophobic - the sewers beneath Cyrodiil's Imperial City, the prison escape through the caves of Skyrim, the vaults of Fallout (so apt, when you think about it, it's almost like that whole series was conceived before Bethesda even had rights to it, just for the studio to have the perfect walkout scenario) - only to emerge out into the grand expanse.

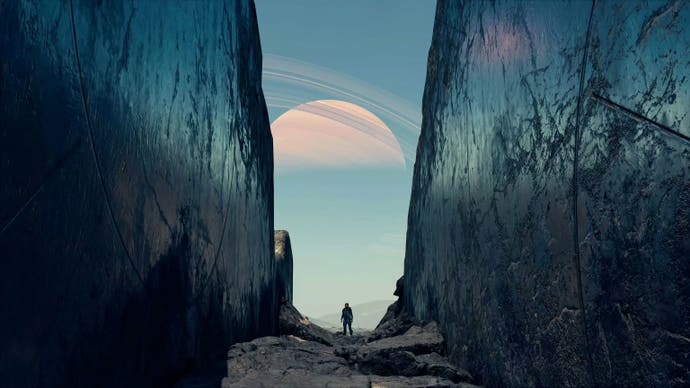

Typically that expanse is something of a showpiece. In The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion it's the beckoning, almost painfully verdant glow of its Ayleid ruin-speckled countryside; in Skyrim the rolling, Pacific Northwest-meets-Scandinavia mix of pine forests and ravines at the region's southern edge. This is what Bethesda does best, basically - and as you can probably tell, I love it. Herein lies the problem: contrast that moment of wondrously blunt juxtaposition, of radical confinement and radical freedom, an unceremonious birthing into a world of peerless possibility, with Starfield, where you burst forth from your grey-brown mining shaft to... a concrete landing pad. Your first view of the wider world is the grey-brown non-place of the planet Argos, the sci-fi equivalent of a car park by an industrial estate off the M4. After a little scuffle here on the outskirts of space-Croydon, it's a fast-travel jump into a largely static tutorial sequence in orbit.

This is Starfield at its worst, one of the handful of uncharacteristic stumbles Bethesda makes delivering its usual sense of wonder, and one example of many small, strange decisions the mega-studio has made that obstruct its own uncanny ability to conjure real video game magic. In this case, I suspect it's because Starfield has just too many systems happening, in too many places, for it to provide one clean route to a totally hands-off release into the world. You need a tutorial for mining, and you need a tutorial for combat, and a tutorial for planetary exploration, and a tutorial for space combat, and a tutorial for space navigation, and on and on. I suspect that's also the reason for many of the game's more major snags. But it's not the totality of this game - neither its only type of problem, nor the only thing to take from a game that is also, regularly, a marvel. It's too big, too oddly shaped and uncooperative, to let you squeeze it down into one summary without falling into reductivity and vagueness.

One attempt, and an understandable one, would be to try and pin Starfield as effectively just a Bethesda RPG in space. Star-rim, Space-blivion, Fallout 2330. That would be mostly but not entirely accurate. In Starfield you can, like those games, entirely ignore the main quest after the first couple of hours to go noodle about on the edges of the known universe, building outposts to help you farm vegetables, mine resources or scan alien slugs. You can take on typically combat-focused encounters with a range of approaches, immersive sim style, by sneaking through undetected or picking grunts off one by one, or lockpicking your way through side doors or pickpocketing keys into control rooms to turn robots on their masters. Or potentially even talking enemies around through persuasion. Or bribing a few conveniently-placed mercenaries to help you out if things turn sour.

Crucially, you can also play with Starfield's astonishing physics, with oceans of potatoes and milk cartons taking on the memeified role here that the avalanching cheese wheels and sweetrolls played in Skyrim - but much more interestingly, actual gameplay scenarios arise from them at times too. Starfield is another "bucket on the head" game, like Bethesda's previous RPGs, that odd and, to me, once-accidental but now clearly deliberate kind of warped game logic working towards something ingenious. It has the same elaborate system of in-universe rules, the bucket scenario being the reliance on sight lines that means an NPC seeing you commit a crime alerts them, but placing that bucket on their head - something that would, I reckon, typically alert a guard to potential foul play in the real world - and then committing that same crime right next to them, doesn't.

The effect is an entire universe of playthings. NPCs as dolls, not animatronic puppets, and Starfield's incalculable amount of bric-a-brac their accessories all there to be toyed with, tossed about, punted off ledges or blasted high into the air in zero-G. In many cases, especially sidequests or optional enemy outposts free from the main story's rigid narrative outcomes - and especially at much higher levels where more abilities are available to meld together in Starfield's bubbling physics cauldron - it means many of the game's limits come down to your own imagination (or, as in my case, lack thereof).

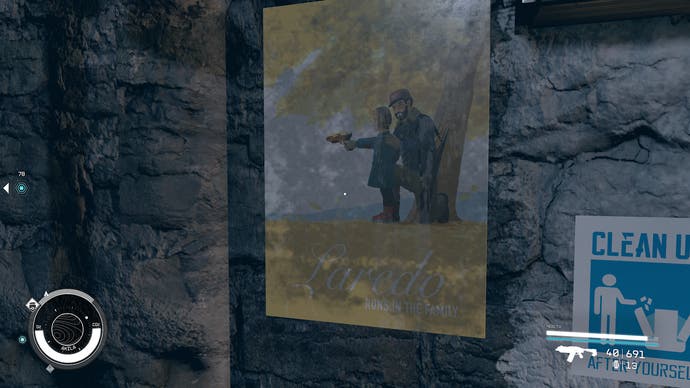

In line with Bethesda tradition again, those sidequests are where Starfield is at its absolute best. It being some time after launch now, you'll likely have already heard about the brilliance of The Mantis, the zero-G gunfights, or one of my favourites involving a ship that left Earth 200 years ago, before the invention of faster-than-light travel, with plans to save humanity by colonising a new world, only to rock up now with humanity cracking on just fine. The genius of that one lies in how Bethesda avoided the straight-ahead approach of zeroing in on all the tragedy and philosophy, and instead had them arrive at a luxury resort planet, the type of place where the galaxy's wealthiest can get a two-for-one deal on reconstructive surgery on their way in and out, to ensure what happens there, stays there. It's a wonderful setup, like a bunch of slightly pompous Victorians spending centuries adrift self-propagating on the Cutty Sark, only to arrive and find their promised land is now an all-inclusive on Mykonos.

Again, the Bethesda formula is plain here - quite remarkably plain in fact. In Starfield there are two main regional factions (Bethesda loves factions) with tense relations after a not-too-distant war. Each also has its own police force, both of which you can join at will for a series of largely interesting, often wonderfully silly quests, like a turn as a secret informant, or a run through a blood-sport gauntlet. There are crime syndicates with their own lines, corporations with theirs, two rivalling religions and a third typically-barmy cult that worships a giant snake. There's a system of bounties, jail, and fines. There are outposts with patrolling guards, subterranean dungeons in the form of abandoned research facilities - oh so many abandoned research facilities. Go into any bar and you'll be relieved to know that 300 years into the future, the archetypal RPG tavern is still alive and well: start asking around and you'll end up with threads of gossip that inevitably turn to quests. Some are comically simple, like one that's literally fetching an NPC a coffee that happens to be from the entire other side of town, clearly a means of getting you to explore the first settlement you arrive in (but, I'm praying, hopefully also a kind of inside joke about fetch-quests in big RPGs? Though going by the number of additional fetch-quests, that may be a little generous). At every corner a quest-giver lies at the ready, hat tipped over their eyes, strange accent equipped, game attitude primed for role-play.

Even in the MacGuffin-hunting, do-gooding secret society of Constellation, the weirdly adulating group of nerds that sends you out from their clubhouse to all corners of the settled systems in Starfield's main questline, you have an almost direct application of The Elder Scrolls' Blades. If the greatness of a Bethesda RPG comes from its network of faction quests, play areas and physics systems, we've got Sky-field through and through. In reality, however, it doesn't - there is a final piece missing from the equation here, and it's a big one.

The great Bethesda RPGs are about exploration and discovery. It's the indescribable webbing of their games that brings the physics and the factions and the playgrounds together and enables them to work as one - the grey matter, the quantum entanglement, the heavy whisking that binds essential elements to form a kind of cosmic emulsion. Maybe that doesn't work. Put it another way: play Skyrim for a while and you'll realise you are really only ever in two modes - doing, or roaming. "Doing" generally applies to ticking things off. So in Skyrim's case: "today I want to power through this Stormcloak questline to get that off my slate," you might say to yourself. "Now I'm going to bash out a few Dwemer ruins and run the loop of looting metal, smelting it, and crafting armour, just to get myself up to the level of making my own Dragonbone gear, then I can start on the DLC." Starfield has loads of doing.

"Roaming" is the opposite of that - or maybe the absence of it - and also certainly all the moments in-between. It's Bethesda's most fertile ground, where it plants memories that, for one reason or another, just seem to stick. The long hike through snowy peaks between Dawnstar and Winterhold, where the wind lifts just in time with the mournful choirs of the score; the time a giant smacks a bandit and breaks the physics a little, sending him a mile or two up into the air. The temptation, from a symbol just at the edge of your compass, poking out of peripheral vision, of a Daedric shrine along a winding commute - or the opposite, the looming, intimidating dread of what you know will be a massive dungeon. It goes beyond the "see that mountain over there" quotes - and the astonishment of when you realise you really can walk all the way there, uninterrupted, for the first time. It's the stillness, the wind between the trees, the mixture of tasks and freedom, action and inaction, space and negative space, that does just as much to give a Bethesda world its still unmatched sense of life as the studio's astonishing clockwork engineering of people and planets in motion.

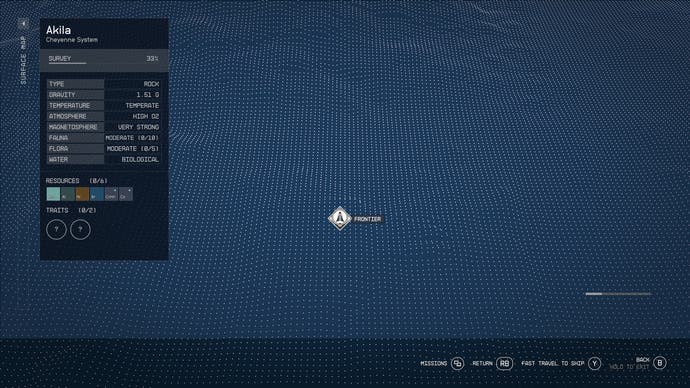

Starfield doesn't have it. It doesn't have surprises along the road, memories of journeys and distractions, a sense of artfully-engineered, perfectly positioned distraction and discovery, like each shrine was hand-placed by Video Game God, because it is both entirely disconnected and, frequently when you do roam about on a planet surface, procedurally generated. In Starfield the planets aren't entire regions, they're fixed cities with random land around them. You can't be lured off the road, or simply on the road to drink in the world, because there is quite literally no road to be lured away from. There's no route from one planet or system to the next. In Starfield, instead, you fast travel everywhere.

It's a topic that's led to much discussion of loading screen waits and broken immersion, the sense of disappointment mostly forming around not being able to seamlessly land a spaceship and take off like you'd hoped. And that's a fair point, but also a failure to really capture what's lost when you cut out manual exploration entirely. Instead of roaming discovery, Starfield's world is navigated by hypertext, flitted through in an instant like a Wikipedia article with all the formless liminality of the internet but without the art of, say, Hypnospace Outlaw or Neurocracy, which actually makes a game of that on purpose.

The result - aside from losing all those sacred in-between moments - is a kind of total disorientation and detachment, a radical alienation and a saddening kind of ennui. In the literal sense, I rarely have the faintest idea where I am in this game. This is because I don't need to - you pick up a quest marker, bring up the menu, press the button to take you directly to whatever planet you need to visit, press another button and pachow, with a whoosh and a bang and, depending on your hard drive, a loading screen or five, you're there. Got the object? Killed the guy? Spoken to the farmer or shopkeeper or whatever? Blam, another whip through the buttons and you're back.

I've been playing Starfield every day for weeks and couldn't tell you the location - or to be honest, the even name - of a single system outside of Sol and Alpha Centauri, and only those two because I know we live in one right now, and the other's close enough for Sid Meier to make a Civ game about it. (I do also know where the Wolf system is, now I think about it - but also because it's right next to those two, has a cool name, and because I spent a good 10 minutes scrubbing the starmap for it while searching for a place to sell my contraband.) I haven't played Oblivion for some time, but I could point to Kvatch or Cheydinhal on a map at the drop of a hat.

Even putting the metaphysical sense of displacement aside, there's also a quite literal one to wrestle with. Humans are in a way homeless in Starfield's version of the future, an interesting narrative angle that's ripe for some of its better moments of storytelling, but one that combines with Starfield's lack of actual journey-making to leave you feeling unanchored, adrift, lost. The exploration that you do embark on meanwhile is a dirge. For a game that has a main story - and a big, central theme, that seeps through its score, its dialogue, its lore - dedicated to exploration, the exploration itself is dreadful.

Take travelling on foot, for instance, which is the only way to get about on any planet, apart from the loading screen trains of Alpha Centauri. This is a reminder of the worst parts of classic Bethesda - the outdated over-gamification of stamina from the likes of Morrowind - where you're constantly looking at your Oxygen and CO2 gauge in the bottom-left and your jump-pack metre in the bottom-right (maybe you're over-encumbered as well, as a treat). Stamina bars have always been present in these games but here they matter because, land on a planet, and you'll find the only things of interest - besides the objective you fast-travelled there for - are absolutely miles away. The cycle is: fast travel to planet, load into procedurally-generated area, observe the washed-out, characterless, almost unanimously ugly surroundings for a distant map marker (and I use ugly for a reason; Starfield's environmental ugliness on most planet surfaces is the ugliness of machines, the authorless sludge of generative AI-art), and run for five minutes in a straight line. If you're lucky, another procedural event might pop up - a ship lands, normally also miles away, or an enemy alien attacks - but that's it. Scan a big lump of space-metal or clear out a few space-bandits, loot what you can find, fast-travel back to your ship (god forbid I do that walk again) and move on.

Discovery meanwhile - the other half of exploration - is also handled differently here. Quests are almost unanimously brute-forced into your inventory through overheard dialogue - usually something you didn't even clock yourself, thanks to Starfield's knack for getting multiple NPCs babbling at once - or through hails from other ships when you arrive (from fast-travel) into another planet's orbit. Bethesda RPGs always do this a bit - heard about the Grey Fox? - but have also always been a treasure hunt, a kind of sifting through busywork dirt for sidequest gold, as you take on some odd jobs or follow hand-scrawled notes in the hope they turn into something truly weird. And this stuff, crucially, is ultimately found by getting out there on foot. In Starfield, where the lack of hand-placed land to walk on means quests must predominantly arrive by interruption, it's closer to an escape room with all its clues pre-marked by waypoint, and an overzealous guide on the intercom who keeps bludgeoning you with hints before you've even looked behind your first suspicious painting.

There are, unfortunately, also just a lot of quite strange decisions in Starfield. Astonishingly, there is no ground map to speak of whatsoever, even in long-established towns, only helping you to feel constantly disorientated and untethered from the world around you. The claim, from Todd Howard, that Starfield would be closer to its more classical, hardcore RPGs seems to be entirely detached from what I played. Starfield would include "some things we didn't do [in more recent Bethesda games]: the backgrounds, the traits, defining your character, all of those stats," he said in 2022, but its RPG elements, at least in terms of things like traits and stats, are the loosest they've ever been.

Starfield's character creator has some absolutely impressive faces and inclusive options, and you can injest some concoctions that get you moving comically fast, which is reminiscent of Bethesda's old-school silliness, but this is still the opposite of a deep RPG setup. In fact Starfield's at least one step closer to "RPG-lite" than Skyrim was: your three traits give you a somewhat gimmicky perk, like the Adoring Fan following you around or a bounty that makes some enemies very occasionally turn up at random, while backgrounds provide a single skill point in three areas that you can earn within minutes of getting started. No sign of governing attributes like the Bethesda RPGs of old. Those skills can get interesting - occasionally very interesting, when combined - but not until far too late in the game, in the region of dozens or even scores of hours after you start. By this point your chosen traits are a distant memory, or a mere annoyance you paid to get rid of for just a couple thousand credits.

The little issues go on. There's far too much time spent in menus - far too much time - and they are finicky, at least on controller, with weird hitches around having to do an extra step like manually undocking your ship from another before performing a grav jump, making two cutscenes out of one. By Microsoft's standards in particular, Starfield's accessibility options are awful and, for a game reportedly delayed for a year for polish, without excuse.

Its "NASA-punk" aesthetic, meanwhile, leads to some quite frankly stunning buttons, switches, knobs, screens, and control-panels, along with the finest selection of doors I've ever seen in a game and an all-round stellar job of spaceship and space-station interiors. These games come bundled with thousands upon thousands of worker hours baked into their world - never mind the thousands of planets - to such a degree it leaves me wanting to single out every person who dedicated years to getting just the right beep-boop out of a computer, or scribbling hand-drawn notes pinned to walls about using the right USB-Z port, getting the shadows looking right on some space pirate's bridge you might never enter, all so this universe can come to life. But compared to all that utterly lavish detail in Starfield's interiors, its planetary surfaces are desperately bland, and its settlements often feel like facsimiles of other places that have done it better.

The Freestar Collective's yeehaw Akila City, for instance, could be straight from Fallout; Neon is a smaller Night City in the middle of a near-barren ocean; New Atlantis is shooting for the "society if..." meme template of a utopian future, mixed with a bit of Starship Troopers satire, but lands somewhere closer to concept art of Neom, that impossibly air-conditioned, crypto-bro investor trap the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's trying to build in the middle of the desert. The thousands of blank NPCs named simply "Citizen", who exist without purpose, make its towns feel like the pop-up facades of more recent Pokémon. In character design, it often lands closer to normcore than anything vaguely punk, with it all being a bit Harrison Ford in Blade Runner 2049, who - admirably! Honestly I respect him for it - clearly didn't fancy the whole plastic raincoats and big collars vibe and just rocked up on set in jeans and a grey T-shirt.

Starfield's story, through the main quest, involves a neat twist on the New Game+ formula and a clever reworking of Bethesda's typical "chosen one" beat, but it also falls back on its old habits of getting you to collect a load of the same object (nowhere near as bad as Oblivion did, mercifully) and relies far too much on people standing around telling you how momentous something is, rather than using scenario or consequence or style to make something feel momentous. The obsession with NASA can feel oddly fawning, and the take on the future - while it's completely understandable to simplify, rather than somehow include the entire world's range of cultures and complexities - is entirely, almost comically US-focused, with no languages or religions carried into the stars, a freedom-versus-union culture war, and not a peep about anyone else's space agencies.

In Bethesda games in particular, meaning comes in the form of a deep submersion into new worlds, and the studio's ability to create a famously unparalleled, impossibly absorbing sense of place... Starfield's problem is its lack of one.

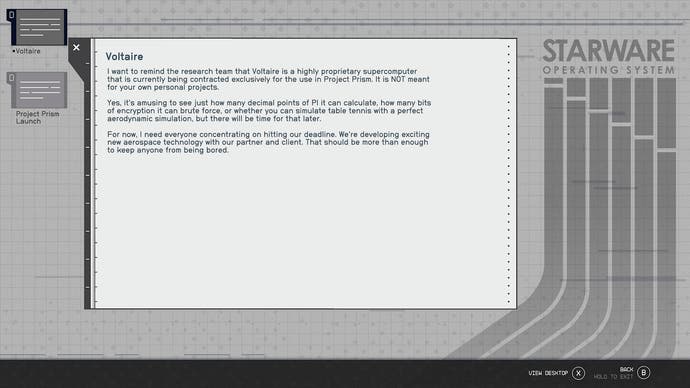

At times, all this obsession with accurate physics that brings about Starfield's most marvellous feats of video game engineering (gravity dictated by planetary locations; local time by the tilts of their axes; those impossible mounds of potatoes), over any deeper engagement with actual human culture, can make Starfield feel like a vision of the future where the STEM kids won the tongue-in-cheek war with the humanities. A kind of playable Neil deGrasse Tyson tweet.

If I were being truly harsh, I could pick up on how many of Starfield's most interesting quests, despite absolutely being interesting, are references to other science fiction tales from the likes of Star Trek or Aliens, rather than creations of its own. Other references are made to older Bethesda games that, without context, can occasionally land as slightly tired jokes, the Adoring Fan one example that just doesn't hit the same on the second telling. Although, absolutely not all of them: the return of another standout Oblivion voice actor is wonderful, with a subtler, more subversive, and as a result much funnier reference thrown in at the end of that questline.

Many of these issues - and hands up, I am admittedly speculating wildly - must surely be down to Starfield's scale. Without it there wouldn't be the need for so many procedural filler activities from quest terminals, so much time in the menus, so much fast travel. The reality, I suspect, is the more you expand in game development and the more you can include, the more likely people are to notice what you didn't include, in the same way you hit upon the uncanny valley with near-real visuals. The harder something tries to replicate the real world the easier it becomes to point out those omissions that would, otherwise, be suspensions of disbelief. In the moments where Starfield clicks, that suspension is entirely possible, the immersion of the immersive sim returns, and Starfield's systemic magic feels as good as it ever has in a Bethesda game, only even prettier and more elaborate.

But the moments where it doesn't are too frequent, and in those there's a sense that this elaborate, clockwork universe has been built without anything human to give it purpose. There's even a scientist, in one of Starfield's many audio logs, that sums this up quite perfectly, using an impossibly powerful supercomputer just to recreate the sound of all the world's ducks quacking in unison. He's fascinated by this, despite his supervisor explaining they have the supercomputer precisely so they can work on the most meaningful research in the history of humankind.

In this world, this mode of thinking that Bethesda occasionally seems to slip into with Starfield where its ambition overrides its purpose, the technical capability is the game - 10,000 milk cartons modded into space! Look what it can do! - but this is not a world I think Bethesda should be aiming to build, unless we want our games to play like that Matrix tech demo for Unreal Engine 5. Technology for technology's sake, or scale for the sake of scale, is a trap. In video games like any other medium, the technical craft, however exquisite, exists to serve meaning, not to be it. In Bethesda games in particular that meaning comes in the form of a deep submersion into new worlds, via the studio's ability to create a famously unparalleled, impossibly absorbing sense of place. Note, for a blunt example, the way Bethesda's games are typically named after their settings, over their people. Starfield's problem is its lack of one. It's a non-place, formless, joined entirely by menu screens and hyperlinks replacing the almost divine sensation of direct experience. Rather than being built in service of presentness and a sense of place, Starfield is set entirely in their absence.