Starship Command retrospective

Trek yourself before you wreck yourself.

"The frontiers of space are frequently penetrated by hostile alien ships ..."

Starship Command did not mess about. From the outset, things were stated boldly. You were nominally in command of your vessel, but you had a specific mission.

"These are tackled by battle starships ..."

Your battle starship was equipped with weapons, scanners and shields. Each command began with you hurtling toward enemy activity at full speed. What happened next was up to you, although what always happened next was that you got into an asymmetric dogfight with endless waves of enemy ships until, eventually, you fired off an escape capsule, ideally before your starship exploded.

"... the command of which is given to deserving captains from the Star-Fleet."

You were one ship, utterly alone in hostile territory, pinpointing targets in a vast starfield and engaging them. And though the gameworld was only sketched in a few throwaway sentences on the title screen, it always felt good to be away from the suffocating bureaucracy of the Star-Fleet. What did those faceless pen-pushers know about space combat? How dare they grade your performance from their space armchairs! Who were they to decide whether you were fit for another mission or not?

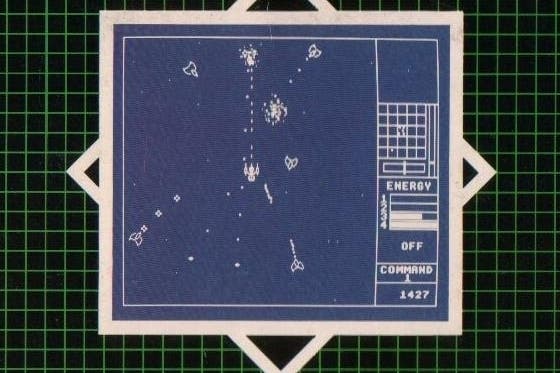

Starship Command was released for the BBC Micro in 1983. I came to it a few years later on the Acorn Electron, the BBC's beige little brother. As one of the launch titles for the Electron, it stood out among the various text adventures and chunky, colourful arcade clones with titles like Hopper, Snapper and Arcadians. This game seemed different, with stark black-and-white presentation and a notably unusual play mechanic. Your starship was locked in the centre of the screen, with the rest of the universe smoothly revolving around it: both a considerable programming achievement and an effective framing metaphor.

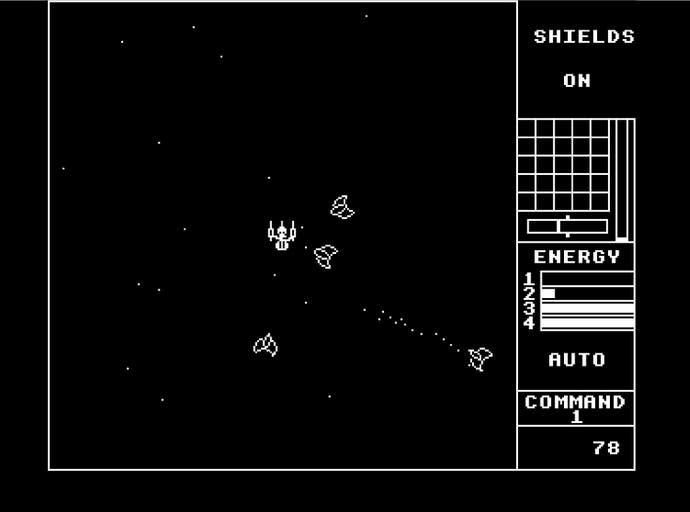

With no bases to retreat to, or power-ups to find, each command was simply a stand-up fight. Using long-range and short-range scanners, you set a course toward the largest concentration of enemies, raised your shields and attempted to take as many of them down as you could.

The sleek enemy ships had variable AI: some would arc onto the screen on a suicide run, dashing themselves on your nacelles and taking out a large chunk of your energy. Some would loiter at the edges of the screen just out of effective firing range. Larger ships had the ability to cloak; they remained invisible, but their bullets did not.

Some fired at you listlessly, as if they were fighting under protest; others released endless streams of deadly dots. Worst of all was the plasma bolt, a glittering asterisk that could shred your shields in seconds. You could almost hear the sizzle as a broadside bore down on your ship. (The actual sound effects were unremarkable.)

Slowly, you dismantled each squadron of enemies, powering your thrusters up and down to draw them into your killzone or to weave around enemy fire. Your ship never actually moved but every thrust or course correction would twist the starfield around you in a vivid simulation of hot-dogging space combat. Successfully destroy a wave of ships and you would instinctively power down to allow your energy banks to recharge, nervously watching your long-range scanners for signs of the next attack wing.

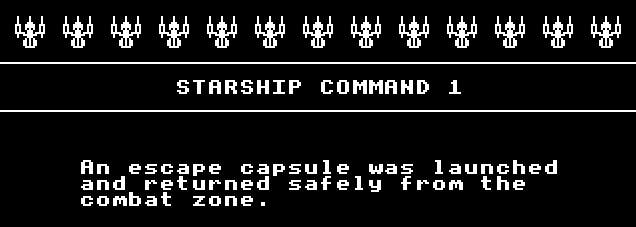

The length of the mission was entirely up to you. You could die in a blaze of glory, ramming your failing starship into one last enemy. But the Star-Fleet was more interested in you returning home for further service. With the option to fire an escape capsule to port or starboard, you had to time your abdication to avoid any unfortunate collisions.

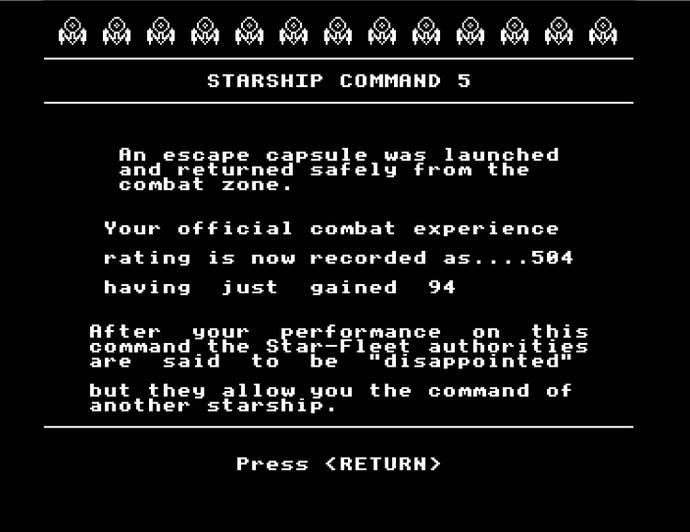

After a successful escape, the Star-Fleet authorities would rate your performance. They were usually "furious" or "disappointed", although sometimes they reached the dizzy heights of "satisfied". Depending on your score, they would then decide if you deserved another starship to command or not.

The first ship looked a little like the Liberator from Blake's 7, while the second was clearly modelled on a certain vessel that boldly went where no-one had gone before. There were apparently eight designs in total, including, on Command 3, one that resembled a lightbulb. Until very recently, the furthest I ever got was Command 5. Each new ship looked excitingly different, but there were no upgrades in weaponry or shielding, even as your enemies became more aggressive. Later commands were a panicky scrap to try and hit the required number of points to continue.

Starship Command was written by Peter Irvin, who would go on to create Exile in partnership with the late Jeremy Smith. You can detect some of Irvin's obsession with simulating physics - attacking ships bounce off each other like bumper cars, and can be destroyed by friendly fire. As in Exile, there is a pleasing sense of player agency and freedom, albeit within the Star-Fleet mission parameters.

The problem, though, was the fact that Starship Command was superseded almost immediately. Elite was released for the BBC Micro in 1984 and with it came a game world light years beyond the bean-counters of the Star-Fleet. From the outset, you could do pretty much what you wanted, in a breathtakingly enormous universe visualised in 3D. Starship Command suddenly looked extremely basic.

Does it have a legacy beyond being a necessary stepping stone toward the creation of Exile? The fixed-ship combat inspired a 1990 Psygnosis game called , but like many Psygnosis title of the time, the actual game was swamped by ray-traced cinematics and unrepresentative box-art. No-one seems interested in Kickstartering an iOS remake of Starship Command. Even the name sounds generic, a placeholder.

But it remains a personal touchstone for me. Three decades after it was written, I replayed it through a gauzy sense of nostalgia. Starship Command still feels like a fully realised project, a properly authored game. It's a beauty.