Steam Greenlight: Is it working?

Eurogamer investigates whether Valve's new system is really beneficial to indies.

When Valve launched Steam Greenlight nearly three months ago it was met with great fervor, but also great skepticism. The service would allow gamers to decide what content they wanted to see on Valve's popular distribution portal rather than leave the decision making process to an anonymous group of judges at the Seattle-based company.

Would this appealing to the masses provide a more honest sense of what people really wanted, or would it cater to whoever had the best PR campaign rather than the best games?

We spoke to several indie game developer in various stages of the Greenlight process to gather insight on how the new system was working.

Early on I spoke to Renegade Kid's Jools Watsham, whose 2D platformer Mutant Mudds gained quite a lot of critical acclaim on 3DS as well as PC, where it was later ported. Incredibly, Valve still rejected Mutant Mudds on Steam prior to Greenlight. "To this day, I do not know why Steam rejected Mutant Mudds," said Watsham. "They do not offer explanations. It is a mystery, locked away in the vaults of Valve."

Watsham seemed more optimistic about Greenlight, where he noted Mutant Mudds sat at 55th place. "I think the concept of Steam Greenlight is great, and it shows that Steam really wants to ensure that smaller indie games have a chance to get onto Steam," he stated. Despite this, he still had some concerns about how it would actually work in practice.

"It's a PR contest instead of a dissection of the games themselves. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it will make it very challenging for a one or two-man team who are focused on making games instead of flexing their PR muscle."

Jools Watsham

"I don't know if there's a perfect way to make such a thing work effectively for everyone," he explained. "The very nature of Steam Greenlight is a popularity contest, obviously, and as such encourages each team to pimp out their campaign to garner votes on Greenlight. It is a PR contest instead of a dissection of the games themselves. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it will make it very challenging for a one or two-man team who are focused on making games instead of flexing their PR muscle."

And yet plenty of the games that have been greenlit were made by tiny teams. Miasmata was made by two brothers, Secrets of Grindea is being developed by three people, and McPixel - the first game to actually go on sale via the Greenlight system - was made by one person.

So how are these games getting noticed? Most of these titles had little to no coverage on mainstream gaming sites, so I spoke to several developers and asked how they promoted their games, or indeed, if they did at all.

McPixel creator Sos Mikolaj Kaminski said: "The largest force driving attention to McPixel at that time were 'Let's Play' videos. Mostly by Jesse Cox and Pewdiepie." This worked out well for Kaminski as he'd tried submitting McPixel to Steam several times and it kept getting rejected.

Bob Johnson, one of the two brothers behind the tropical survival horror game Miasmata, said he and his brother Joe did very little to promote Miasmata prior to Greenlight. "We had a YouTube video with 20k plus views and a few small blogs posted about our game. Greenlight has been the single best promotional tool for us."

"I think people voted for Miasmata because it was obvious that it was a polished, ambitious, good-looking game done by a couple of passionate and talented people," he explained. "It wasn't derivative or another homage to 8-bit glory days and people responded to it. If that isn't a case-study for why Greenlight works, I don't know what is."

Johnson decried the notion of it simple being a "popularity contest". "If that term is used as a pejorative and is implying that undeserving games are making it to the forefront en-masse, then I disagree. Steam users are a well-informed gaming audience. It seems to me they've done a pretty good job selecting games with merit."

"Greenlight has been the single best promotional tool for us."

Bob Johnson

He admitted that the cream doesn't always rise to the top, though, and some level of PR is required. "If you value PR work so little as to dismiss it as 'pimping', it is unwise to expect people to ever find your game, let alone be able to make an informed decision about whether they want to purchase it or not," he added. But by and large he found that having a polished looking game - and one with a novel conceit - is enough to stand out.

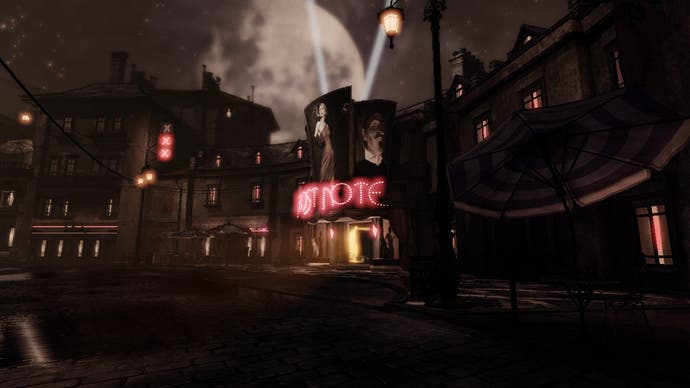

Sam Abbott from Compulsion Games, whose surreal 1920s vaudevillian puzzle/platformer Contrast has been accepted on Greenlight, likewise did very little external PR (aside from having an article in GameInformer) and found that "Greenlight is marketing".

"When you put your game up on Greenlight you have access to a massive pool of people who are interested in what is going on and are critically assessing your game against others," he said. "If you put an unpolished, poorly explained and unoriginal game up, you're not going to win many people over. If you put up something that looks good, is explained well and shows some innovation/character, people will vote for it. Presentation matters."

Abbott theorised that external marketing was overrated and does little to push votes. "Think about it - what kind of marketing available to indies is so effective that it convinces people who aren't already into the scene to a, sign up for a Steam account, b, search through Greenlight for your game, and then c, vote?"

"It's a hassle. Some people will do it, but the best you can realistically hope for is that people who are already on Greenlight may go and vote for your game, which they should already have done if your Greenlight page is good." He also noted that Greenlight offers next to no traffic stats, so it's impossible to tell how effective your marketing efforts are.

According to Abbott, the Greenlight community is "engaged, positive, and discerning" and he found few trolls and mostly constructive criticism. "External communities (apart from Black Mesa, Postal 2 etc) are mostly irrelevant," he said. "They only matter when they are so big that they can make a dent in the ordinary Greenlight traffic. We know there are at least 200k+ people on Greenlight, so it needs to be a pretty big community to influence the voting significantly."

The already greenlit RPG Secrets of Grindia similarly had almost no external PR. "We spend nearly no time on PR, except for a weekly recap on our blog," said developer Pixel Ferrets' Teddy Sjöström.

"It would seem there are actually a significant number of Steam users who do take their time to traverse their Greenlight queues once in a while, and we believe our graphical style and level of polish helped reel many of those users in."

The surreal first-person adventure Dream also made the cut on Greenlight, with only the three-person team at Hypsersloth behind it. Developer Lewis Bibby noted that Dream had only been in development for three months before the studio put up a Greenlight page with just a trailer and description.

"As we monitored Greenlight over the first few weeks before we were greenlit, it was very apparent that the majority, if not all, of our competition were games that already had a fan base behind them or were even sequels to already successful games," said Bibby. "So we're of the opinion that popularity plays a role but it's not impossible for never before heard of games to make it through and even if it's the minority it makes the system worth it."

Outside of those accepted, other indies seemed to appreciate Greenlight's relative transparency. Nomad Games commercial director Don Whitehead, whose upcoming board game adaptation Talisman Prologue is on Greenlight, said, "The process before was you submitted to Steam and then you just waited and waited and waited. Now there's some visibility on where you are in the process. We're not quite there yet, but we're in good shape."

So Greenlight seems to be doing well for first time developers, but how about those who previously had games accepted internally who are now being asked to go through the less personal Greenlight process?

That's the case for indie adventure game publisher Wadjet Eye, who's now being asked to submit its sci-fi point-and-click adventure Primordia to Greenlight after its previous title, Resonance, had been accepted by Valve almost immediately.

Wadjet Eye founder Dave Gilbert didn't seem particularly discouraged by this. To him, rejection from Steam was par for the course. "Gemini Rue, our runaway biggest hit, was rejected twice by them before they finally accepted it," Gilbert explained. "In fact, Steam has rejected almost every one of our games only to change their minds later, so this situation is nothing new!

"I sent our Primordia pitch (which included several preview quotes from the coverage we gathered, basically the same way we'd pitched Resonance) to my usual contact at Steam, but I received a boilerplate rejection letter from somebody else I hadn't spoken with before. It was the same letter that I'd seen before, but with the addition of, 'I highly suggest putting together a page on Steam Greenlight.' Lacking any other option, that's what we did."

"If a developer has already published on Steam they are likely but not guaranteed to skip Greenlight and go directly to the publishing phase with a new title."

Doug Lombardi

This may have seemed like a slap in the face to a proven developer whose work was previously well received, but Gilbert was beaming at the reaction the community had to Primordia. "We're really happy with the response on Greenlight so far," he said the day after the Greenlight page had launched. "The fan support that has risen up behind this game has been nothing short of mind-blowing. It's been more gratifying than I can possibly say."

Despite having to go through the Greenlight rigmarole, Gilbert liked the idea of Greenlight because it functions as a way for the audience to prove to Valve what people really want to play. "Greenlight seems like a good idea for indies who have already built up a fan following, because it gives them a way to show Steam there's a demand. I wish it had been around when I was first trying to get Steam's attention!"

And why is it so important to get onto Steam, you may ask? Gilbert noted that Wadjet Eye's Steam Sales had done at least 10 times that of its direct sales.

So does Wadjet Eye's rejection mean that Greenlight is the only way for developers to get their games on the service?

Not so, apparently. "When a new submission comes from a developer we haven't worked with before, it's likely but not guaranteed that the title will be directed to Greenlight," said Valve's Doug Lombardi. "The inverse is also true - if a developer has already published on Steam they are likely but not guaranteed to skip Greenlight and go directly to the publishing phase with a new title. Sometimes there will always be edge cases where more information is needed."

It would seem as if Primordia was one of these "edge cases," and it's Valve's policy not to disclose why certain games get rejected.

While Steam Greenlight seems to be doing a lot of good for the indie scene, that doesn't mean it can't be improved. Even Valve head honcho Gabe Newell admitted that the company could do a better job at filtering content.

“I don't think we did a super good job [with Steam Greenlight]. We have a bunch of work to do," Newell said in a recent interview with 4chan's /v/.

"I don't think we did a super good job [with Steam Greenlight]. We have a bunch of work to do."

Gabe Newell

“First of all, there's way too much between a game developer and getting something on Steam. It's really because we've been kind of stupid about the amount of work we have to do - just to process everything applying on Steam is 20 or 30 peoples' work. We need to make that process much more efficient," he added.

“So Greenlight was more about, 'Why don't you guys choose which one we should turn the crank on', rather than, 'Let's just focus on making turning the crank easy, so that anybody can put it up'. Greenlight is better than nothing but still not where we really want to get to.”

These were pretty vague criticisms, so I followed up with Valve, to which Lombardi replied, "We have said all along that this will be an ongoing project, and we have a very long list of things we'd like to add." I'm afraid that's all we're getting for now.

Ultimately, Greenlight seems to be improving the submission process for indies; those who've been accepted are thankful for it, while those that haven't are finding their chances are better than under the previous "behind closed doors" internal process. That being said, there's still something not quite right about it that we haven't quite put our finger on.

"It's hard to say what can be improved," said Gilbert. "There's no doubt that having an existing following and fanbase has helped our Greenlight campaign significantly, and those who are just starting out would find it a much greater challenge. But in all honesty, it's no different than the way things were before... The only difference now is that instead of trying to get the attention of an overworked staff member at Steam, we're trying to get the attention of the gaming public.

"This turns it into a PR campaign, and a bit of a backwardsy one. Now you have to sell the game to the public to get votes in order to sell your game on Steam... so you can sell it to the public for real. I'm not sure how that can be fixed exactly, but something definitely feels a little off about it."