Strider retrospective

Blade runner.

With no real desire to work in video games, young Kouichi Yotsui joined Capcom as a means to pay outstanding loans from his college film project - a financial burden made heavier by his use of expensive 16mm film. There, at the recommendation of mentor Shinichi "Yossan" Yoshimoto, co-designer of Ghouls n' Ghosts, he wrote a treatment for a game that caught someone's attention within the creative hierarchy. Although it would never see the light of day, it instilled enough confidence to place Yotsui - credited in-game as "Isuke" - In the driving seat of a new three-tiered collaborative venture.

His fierce ambition would shake up the industry. Accompanied by a Famicom title and a bookstore manga, the arcade release of Strider Hiryu is regarded as a landmark of innovation. Abandoning established platform parameters in favour of a diverse play area built of scalable slopes and objects, it ditches Black Tiger's edgy shuffle and Bionic Commando's telescopic clambering in favour of a light-footed raid through a dark and distinctive future. You play as Hiryu, the youngest A-ranked Strider ninja, on an assassination mission to Grandmaster Meio's orbital hideout The Third Moon. A stunning premise memorably realised, there's still little to challenge its strength of concept in over two decades of industry evolution.

Yotsui's liberties with real-world particulars embellish the game a bleak despotic air. Embossed with hammer and sickle symbolism and a smattering of Russian text, it's the 2048 of an alternate reality: a Socialist dictatorship where guards patrol in Soviet overcoats and Meio rules the world with an iron fist. Our eponymous hero glides in on a starry city night, landing behind enemy lines in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic - what was once a real republic under the Communist Soviet Union until 1991 before becoming today's independent Kazakhstan.

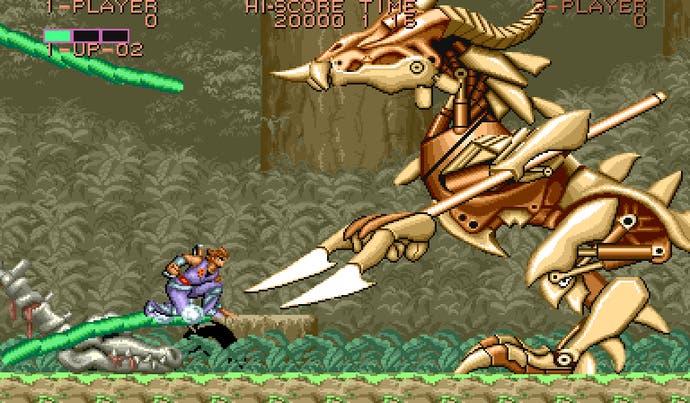

A footnote to video gaming's first commercial decade, the scope and flexibility of Strider's sci-fi playground was a brave novelty. A liberating blend of untethered movement underpinned by swift, pinpoint technique, Hiryu's ability to rapidly slash is never impeded and his attack range is considerable, Cypher plasma sword splitting the air with an enticing zing. Bolstered by encircling bipedal droid satellites and robot panther power-ups, at full capacity his blade comfortably reaches out to erase enemies several feet away, circumventing projectile pickups in favour of pure ninja laceration. You can slide along the ground, cutting through Meio's grunts with razor tipped soles, and tumble through the air while your Cypher fires away, dismembering enemies in a magnesium tinged flare.

Strider 2 - created long after Yotsui's departure from Capcom - was lambasted for its compartmentalised, vignette driven levels, chiefly because its predecessor features some of the most remarkable contiguous stage layouts in 2D gaming. The antithesis of something like Taito's 1987 scrolling action game The Ninja Warriors, Strider has little to no instances of repetition and zero respect for formulaic stage design. Proffering an orchestrated rollercoaster of steep ascents, downhill dashes, and epic sky-high battles, its assembly of pitfalls flow effortlessly from one set piece to the next.

Stage two sees Hiryu's one-man-army infiltrate a remote outpost in the Siberian mountains, demolish a robot gorilla sentry, and scale a vertical shaft into room of rotating gears. Emerging on a snowy mountain peak, you battle jetpack-wearing bounty hunter Solo, outrun an explosive rolling slope, and cartwheel across a ravine into a weather factory bristling with electricity. Upwardly jump, swing, and clamber through the conductive field, and you're charged with navigating a series of flying patrol vehicles, eventually reaching a bomb-raining craft where you spar with three Chinese Kung-Fu siblings before butchering the driver.

Raw Japanese creativity fused with the inspirational fantasy themes of 1980s media, Strider's bold sprites and vast environments achieve an enveloping sense of scale; a broad cinematic canvas of flying warships and interplanetary skirmishes, detonating scenery and rapid escapes. Star Wars grandeur played out with the bombast of a Schwarzenegger crescendo, you're barrelled through events with action movie momentum, skidding down corridors, clinging to burning scaffold, destroying laser webs, and, in the most abrupt thematic departure, dicing Amazonian tribes and dinosaurs in distant rainforests.

Booming cut-scenes voice acted in Russian, Chinese, Japanese and English stitch the stages together, establishing a fleet of iconic villains. The Ourobouros, a serpent boss formed by a committee of shape-shifting Kazakh officers, is followed by pirate commanders, gravity cores, and eventually Meio, whose monstrous pre-battle repartee bellows "All sons of old Gods, die!" right before you launch into his off-world rig to put his lights out.

The audio, an avant-garde score by Osaka Music School graduate Junko Tamiya, is the perfect marriage to Yotsui's oblique world: a surreal and often discordant arrangement that's key to the game's uncommon personality.

Under burden of such an explicit vision, Strider's free-wheeling drive isn't without a few critical bugs. Although far less prominent than in Sega's Mega Drive port, the stage two flying vehicle transit can go incredibly wrong if you find yourself knocked through a platform, and the gravity room's inertia occasionally likes to fling you right out of the play area. In the final ascent to Meio, dropping through your multi-sprite transport is probably the most heinous of all coding imprecisions. But these occurrences are fleeting, especially when the game is properly learned - which at only fifteen minutes in length is a surprisingly simple task. That it's one of the easiest one-credit clears in the arcade spectrum is likely intentional: a director's bid to demonstrate the full extent of his invention to as many people as possible.

Wielding the video game medium as a vessel for his film aspirations, Yotsui's endeavour skirts a dangerous line between success and failure. In considering video gaming a mere stopgap, it's a product of self-centred experimentation that inadvertently demolished boundaries. Seizing the opportunity to produce something filmic, Strider feels blithely unconcerned with risk-taking on behalf of Capcom's bank balance, making it less a picture of coding perfection than it is a spectacular dramatic feat.

After running over budget and over schedule, Yotsui left Capcom soon after the game's release. His later works include text adventure Nostalgia 1907 - responsible for financially wrecking developer Takeru/Sur Dé Wave - and bomb-diffusing simulation Suzuki Bakahatsu: both achieving only cult followings in lieu of poor commercial performance. But under Mitchell Corp., a developer made up of migrating ex-Capcom staff, Yotsui came close to recapturing the magic with 1996's Cannon Dancer (or Osman, as it was known outside of Japan), an arcade-only spiritual sequel to Strider. A comparable action showcase, its sinister plot-line of corrupt capitalist governments apparently hints at his experiences under Capcom's bureaucracy.

Today, Strider is an established staple of popular culture, its red and blue hero symbolic of a milestone in gaming advancement. The reckless fervour of its young director and his bid for cinematic grandstanding could easily have crashed and burned, but for Kouichi Yotsui it seems the moons were aligned - all three of them.