Suikoden Tierkreis

Fated.

A new generation of consoles is almost always seen as a good thing, upgrading our gaming experiences in previously unimagined ways. Sprites turn to polygons, full-motion video cut-scenes make way for in-game storytelling, and soundtracks once performed by Midi orchestras are now recorded by Philharmonics. But the cost of this evolution is absorbed by game-makers, whose task it is to realise the machines' vast but expensive potential. With such broad boundaries, their games now take ten times as long to make and cost a hundred times as much they once did. The knock-on effect is that, perhaps for the first time ever, some genres are simply no longer feasible for anyone but the biggest players.

So it is for the Japanese RPG. Today the sort of winding, 60-hour, world-touring epics that flooded the PlayStation's library are prohibitively expensive to make, certainly costing more than the genre's niche fanbase can support. Which series beyond the Final Fantasies and Sony-funded White Knight Chronicles of this world can afford the next-gen treatment? This has left JRPG developers with one of two choices: let their modestly-successful series continue to play out on last-generation hardware - as in the case of Persona, Grandia, Wild Arms and Valkyrie Profile - or, like Konami with Suikoden, head to the handhelds, where the technology is still sufficiently restricted to make a long-form epic affordable.

Konami's flagship RPG series has never been characterised by technological superiority, instead building its small but vociferous fanbase on gritty storytelling and a narrow, collect-'em-up focus. But despite the developer's best efforts to make the most of what they have here, ironically Suikoden Tierkreis is clearly a game made on a limited budget. As with the early PlayStation JRPGs, woefully basic 3D characters run about on still, flat CG background pictures. No matter how pretty these locations are - and the lush, green pastoral vistas have an inviting charm - pictures they remain, lending an anachronistic sense of disconnect between character and environment that never quite dissipates.

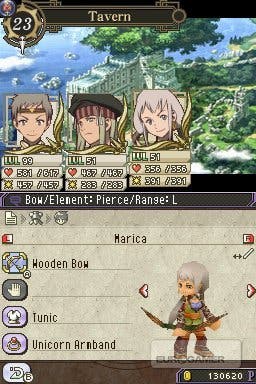

There's the odd treasure chest to be found as you move through the forests and ruins of the game world, but these discoveries are the full extent of interactivity when you're exploring. Many scenes are reused in multiple locations - inns always look identical, no matter which town you're in - and the squat 3D models that represent your characters are so basic that they're almost indistinguishable from one another. Navigation around towns is carried out via a straightforward menu system, as is exploration on the world map, reducing the game's locations to a list of disconnected scenes chosen from a drop-down menu. During battles the top screen is used to display your squad's vital statistics, but at all other times it displays nothing more than a rather lacklustre CG still of your current location. Despite the artistic flair that permeates the game, this is nonetheless a Tesco Value RPG.

And yet, despite this, Suikoden Tierkreis emerges as one of the better traditional RPGs for the DS. In part this is thanks to the game's central conceit, which has run through most of the series and continues in fine form here: army building. The series has always tried to take a more realistic approach to the business of world-saving. It supposes that, if a small band of youngsters really did band together to save the world from a common threat, they would be able to convince a least a few of the people they meet along the way of their quest's importance. In Suikoden Tierkreis there are 108 recruitable party members scattered throughout the world, characters just waiting to join the cause, and, as with Pokémon, much of the game's appeal comes from trying to gather them all.