Sunless Skies is a very British garden of horrors

Something awaits you.

"The empire on which the sun never sets, and whose bounds nature has not yet ascertained," George Macartney wrote of Britain's colonial territories in 1773. In the universe of Sunless Skies, an everlasting Queen Victoria has made this fond pronouncement a literal truth, replacing Earth's sun with a clockwork star, a sun that sets only because her Majesty wills it. The Empire, what's more, has come to reign over not just outer space but the very raw material of time - unearthing minutes like ore from the drifting ruins of the Reach, one of the new game's four discrete regions, and using them to accelerate construction projects or cruelly drag out prison terms, amongst other things. As a budding steamship captain, you too can get in on the trade, shipping wax-sealed casks of unseasoned hours alongside "everyday" commodities like aborted lab experiments or crates of human souls. It's both a parody of how empires construct their own realities, their own, brutal systems of measurement and definition, and something that hits a bit closer to home - a send-up of the energy-based mechanics of freemium social games like Failbetter's original text RPG Fallen London, where time is indeed money, a thing you can stockpile.

It's certainly worth setting aside a few barrels of hours for Sunless Skies. Available now in Early Access, the game seems just as debauched, poetic, gruelling and mesmerising a creation as its ocean-going forebear, Sunless Sea, if possibly a little too familiar for its own good. As gloriously warped as the supporting fiction is, this is a game with a simple core - travelling from port to port across a 2D plane in your clanking steam-powered vessel, carrying out oddjobs and obtaining even odder artefacts as you embroil yourself in a series of invariably sinister, very open-ended short stories.

The shift from an underground ocean to the interstellar void is accomplished with barely a ripple - you can now strafe or boost sideways to get the drop on an enemy vessel in combat, but the process of peeling back the world map's fog of war while managing your supplies, fuel, inventory and stress levels otherwise feels exactly the same. As a role-playing exercise, the game seems less in hock to bare stat-massaging than its predecessors - levelling up now takes the form of choosing a Facet or Deed rather than just spending points, which both boosts your stats and applies a twist to your backstory. Perhaps you were once subject to splendid, hellish hallucinations. Perhaps you only pretended to be cured of them. Such tweaks notwithstanding, you can expect a strong element of grind throughout - large amounts of certain commodities are needed for certain stories - complicated nowadays by the fact that fuel and supply items can no longer be stacked, forcing you to expand your hold early on if you want to make your reputation as a trader.

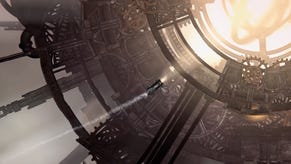

Speaking of hellish hallucinations, the immediate thrill of Sunless Skies is to explore Failbetter's inimitable representation of outer space - an environment more vegetable than void, where you'll encounter huge, spiralling vines lost in a nebula of pollen, towns built atop translucent asteroids of fungus, and the bleeding wrecks of unnamed cosmic monsters, jaws gaping horribly in the backdrop. It's a vision that takes inspiration from how early sci-fi authors like Jules Verne made sense of the wider cosmos by translating it into the language of the ocean, mixed up with liberal nods to Lovecraft and Ancient Greek mythology. Settlements, meanwhile, are vivid studies in Englishness - High, Little, Middle and otherwise.

There's the bustling industrial burg of Port Prosper, where you can while away an evening at the pageant of the Red Saint, a reworking of St George's Day in which the streets are hung with posters of vivisected dragons. There's Port Avon, a homage to the mean-minded insularity of those too-perfect country villages, where you'll soon "wear out your welcome" unless you arrive armed with crates of tea or scurrilous tales from the big city. There's Titania, a preposterous bohemian commune erected on the petals of a gigantic flower that is regularly raided by giant vacuum-proof bees, and Carillon, a sanatorium run by kindly devils where you can earn various flavours of penance and offload any souls you've come across in your voyages. The new game benefits, in each case, from some lovely visual enhancements over Sunless Sea - you can make out vast networks of gardens, temple domes, refineries and statues stretching beneath the navigable plane, and there are more in the way of animate flourishes such as bunting flickering around the edges of a village green.

Failbetter's taste for the foppery of Victorian Britain is perhaps starting to verge on self-indulgent - there are only so many references to crinoline and pipe-smoking I can swallow in one sitting - but the writing in general remains as sharp as you'd expect from the creators of Fallen London. Characters don't have names but arch sobriquets like The Fatalistic Signaller or The Rhapsodic Mayor - titles that speak to both a society fuelled by conspiracy, and an underlying play of psychological and mythological archetypes. Every story is an eldritch knot of hints and surmises couched in a few, brisk paragraphs, every item or trait a curiosity, be it a Vision of the Heavens or a plate of stained glass. There's the occasional dud line, but most are darkly delightful: of "Savage Secrets", for example, the game notes only that "Truth is brutal; brutality, truth". The accompanying art is more lustrous this time around, with decadent city scenes and character portraits sitting alongside the text, but it still has the tightly-packed, suggestive quality of a really well-wrought boardgame prop. There is always so much more going on here than you can see.

This being an Early Access build, there's obviously an awful lot still to be added - regions, ports, items, systems, characters and the effects of a persistent war between the British Empire and an army of independent-minded colonists. One thing I particularly miss, right now, is a sense of dread: the wild, shifting colours of the Sunless Sky simply aren't as menacing as the crushing darkness of the Sunless Sea. Your terror levels will creep up just as relentlessly during exploration, but where losing your mind was the previous game's calling card, here it feels like a purely practical problem - another gauge to keep an eye on alongside your reserves of coal and food.

Perhaps the issue is that there's no longer an actual light/dark mechanic, whereby you'd flick your ship's spotlight off to sneak around pirate vessels or sea creatures at the risk of panicking your crew. Perhaps it's that there's no sign yet of Sunless Sea's three treacherous deities, Salt, Stone and Storm, and thus nobody to sacrifice to for aid when you're stranded. Submitting to the dubious whim of a god was one of my favourite aspects of the previous game - I can only hope Failbetter has something equivalent in store for this one, down the line. Cannibalism is still very much an option when push comes to shove, though, and the tales of woe and derangement you unlock at higher terror levels seem every bit as unwholesome as when probing the Underzee's murkier corners. At the time of writing my ship is being closely pursued by... something. It's possible I could get rid of that something by steering into clouds of debris, at the cost of a point or two of hull strength, but perhaps it would be more engaging to let the story reach its natural conclusion. As ever with Failbetter's games, there are few ghastly implications so ghastly that you don't want to see them play out to the finish.