Super Columbine Massacre RPG - Part 2

Have videogames gone far enough?

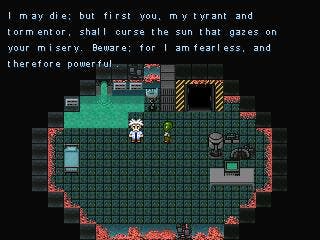

Super Columbine Massacre RPG!, is a homebrew RPG in which players take on the roles and actions of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the two killers in America's most deadly school shooting. The game has attracted worldwide criticism for its subject matter despite the fact numerous award-winning books and films based around the event have been released. Last week the Slamdance Independent film festival announced it was removing the game from its Guerrilla Gamemaker prize short-list citing fear of public backlash as its reasoning.

Eurogamer spoke to the game's creator, Danny LeDonne, and Ian Bogost, assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, a vocal supporter of the game to discuss the issues that this bedroom-coded 16-bit styled RPG has flung centre stage at the start of 2007.

Read Part One to catch yourself up.

The idea that videogames can allow a player to take on the role of an antagonist is not a new one. Fable and Knights of the Old Republic were both recent titles that gave players the option to role-play as an evil character. The difference with SMCRPG is that the position is forced upon you as you recreate real life horrors. While the effect was clearly deliberate, Eurogamer asked why it might be important for games to facilitate playing such roles?

"We can learn about the system of ideas, values, historical circumstances, and personal feelings that drove their decisions," explained Bogost. "I'm sure every American wonders how and why the 9/11 hijackers could choose to commit the acts they did. Is it enough just to wonder? Should we not try to understand? Understanding and empathy does not mean apology or excuse. It's worth flipping this point on its head: from the hijackers' perspective, what do you think someone can learn by playing a game in which people value global capitalism over faith? In which people can learn to become soldiers of America's Army to pursue that goal? Who gets to be right?"

"I think the opportunity to walk a mile in someone else's shoes is an experience that videogames can uniquely give us," agreed LeDonne. "Play the McDonald's Videogame or Darfur is Dying or Disaffected. How does it feel to run a corrupt multinational corporation? How about being a refugee in the Sudan? What about working at Kinko's? Games offer a window through which we can see the world a different way. I suppose that's a lofty jump for some people to make and as a result videogames are often scrutinised because the power of role-playing (as psychologists know well) can be very potent. But I think this is something to study, redefine, and embrace... not flee from."

Custer's Revenge, the Atari 2600 game from 1982, gained notoriety for casting the player as General Custer tasked with overcoming various obstacles in order to rape a Native American woman bound to a post. The game received widespread criticism, not just because it was a terrible videogame, but also for its content. Eurogamer asked both men whether they thought that videogames had to present a worthy point in order for offensive interactivity to be permissible or if meaningless sexism and racism could be validly portrayed?

"We shouldn't confuse expression with sensationalism and offence," noted Bogost. "Custer's Revenge was probably created to offend, not to inspire or raise questions in its players. That is not because it depicts rape, by the way, but because it fails to offer any meaningful perspective on rape, from a historical perspective, from the perspective of the perpetrator, or from the perspective of the victim."

"Well, for me," LeDonne added, "the 'worthiness' of a point isn't exactly something we can measure with a ruler. One of the most important nuances of free speech is the understanding that one's personal estimation of 'poor taste' is a weak means of examining the value of any particular expression.

"It's important to remember that while Birth of a Nation is a deeply racist film by today's standards, it is also an important landmark for filmmaking itself. Perhaps the same importance cannot be placed on Custer's Revenge but nonetheless perspectives of sexism and racism should have the same accessibility in videogames as they do in a variety of other mediums. Watching Triumph of the Will or listening to Nirvana's Rape Me can be very valid experiences for an audience to have. So long as an issue exists in the real world, artists will feel compelled to represent it in their work... including videogames.

"One of the ways in which SCMRPG differs from Custer's Revenge, in my estimation, is the depth of the perspective SCMRPG offers and the factual nature of the game's content. However, the basic idea that the player can take on the identity of a morally unwholesome character is shared by both games and I believe a valuable exercise. How do we know who we are unless we know who we are not?"

It's this kind of denial of any ineffability in videogames that perhaps most scares videogames' detractors. Eurogamer asked both men if they thought any act was truly permissible in a videogame and, if so, why. "Yes," argued LeDonne. "If games are to truly explore the world we live in instead of merely allowing us to escape from it whenever we press the power button, then games need to have the artistic license to approach any subject. I think it is possible to make a game on virtually any topic that comes to mind and the game should be evaluated on its content rather than its form. Is there any subject matter that should be off-limits for sculpture or acrylic? Of course not. What matters is what the work contains."

"I agree," added Bogost. "No topic is off-limits to art of any kind. We must not be afraid to try to understand our world, even if such progress seems difficult or dangerous. Clearly there are more and less meaningful ways to simulate any topic. But no subject is a priori off limits. It is then the job of the critic to tell us whether it is good or successful."