Switch's eccentric new hardware is a link to Nintendo's past in the most exciting way

Arts and witchcrafts.

In the run-up to Nintendo's announcement last night, a few of us were bandying around ideas about what it could possibly be. An Amiibo-focussed game, Nintendo's own version of Skylanders? A streaming service that brought together the best in kids TV - so you'd always have an episode of In The Night Garden to hand through your favourite Nintendo device?

How small our imaginations were, and how glorious it is to be blindsided by Nintendo again.

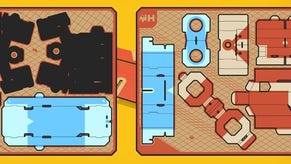

Labo, the bevvy of cardboard appendages that turn your Switch into a piano, a fishing rod, a doll's house and so much more, is a reminder that Nintendo remains unashamedly, unapologetically and somewhat brilliantly a toymaker at heart.

This is an idea from leftfield, perhaps as pure an expression of Gunpei Yokoi's well-worn philosophy of lateral thinking with withered technology as there's ever been at Nintendo. Labo looks like nothing more than a product of Nintendo before Mario - as expertly chronicled by Erik Voskuil on his outstanding blog and in an accompanying book which I can't recommend highly enough - when engineers and designers such as Yokoi would conjure up such delights as the Ultra Hand, the Love Tester, or my own personal favourite the Lefty RX, a radio-controlled car that was kept affordable by limiting itself to components that only ever allowed it to turn in one direction. There was even, as former Nintendo employee Ashley Day pointed out in the wake of last night's announcement, a range of foldable cardboard toys produced some 40 years ago.

They're wonderful inventions all, and in its more modern guise Nintendo has always shone brightest when there's been flashes of that same imagination in its video game hardware. The Game Boy is oft-cited as a prime example of this (even if, in recent years, the extent of Yokoi's involvement in its design has been called into dispute), going against the grain of more technically capable competitors such as Sega's Game Gear and Atari's Lynx and ultimately winning out with its beautifully stripped back and famously durable design. The Wii, which flew in the face of the HD generation, is another example of a clever device proving that it's the thinking rather than the technology that makes great hardware.

The Wii never really sat well with the 'hardcore', that ill-defined and I'm pretty sure mostly imagined crowd that supposedly prefers its video games served up with a straighter face, but beyond the shovelware that clogged up a fair amount of its library there there was a sense of anarchy that best summed up all that was good about that particular era of Nintendo. Where else could you find something like Let's Tap, Yuji Naka's compilation that, like Labo, came complete with its own cardboard box to bring its action to life?

There are elements of that same philosophy to be found in the Switch, and I'm fairly sure the success of the machine can be in part be attributed to how Nintendo's forged its own path - and, unlike with the Wii U, forged one which a large number of players are more than happy to follow them down. Not happy with that, though, Labo is a play to open up the Switch to an even larger audience, and if the spark of imagination evident in the reveal truly catches then there's every chance it'll do just that.

Immediately prior to Labo's reveal there were warnings that perhaps this wouldn't be for more seasoned players, though I beg to differ on that point. For aficionados of the Kyoto outfit like myself and many others, Labo gets to the very heart of what makes this company so fascinating and what sets it apart from its competitors. Labo looks like nothing less than the very best of Nintendo.