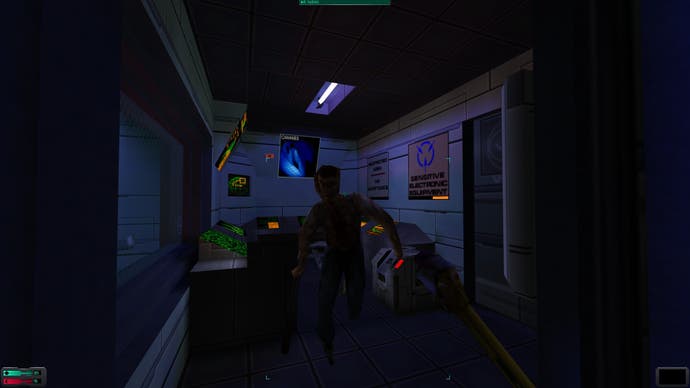

System Shock 2 still stands as Irrational's finest work

Immortal machine.

2007's BioShock blew everyone away with its momentous second-act twist. The scene in which you finally encounter Andrew Ryan, your body buzzing with adrenaline after the rigmarole you've gone through to find this megalomaniac, only to be delivered the debilitating narrative gut-punch that you've been guided like a puppet the entire time, is often considered one of gaming's greatest feats of storytelling. In fact, so successful is this scene that it ends up hurting the remainder of the game. The flurry of half-baked ideas that follow - your plasmids don't work, you're sort of a Big Daddy - fail to rebuild the momentum which leads up to that clarifying moment.

It's also surprising that, at the time, more people didn't see it coming, as the setup and delivery echo an equivalent reveal penned by Ken Levine in System Shock 2, the game to which BioShock was marketed as a spiritual successor. On deck four of the ill-fated spaceship Von Braun, the character you've been working with for the first half of the game turns out to be the dead puppet of SHODAN, the malevolent AI introduced in the original System Shock.

It's only when you examine the two side by see that it becomes clear why this is. Both are games dedicated to the exploration of player agency, or more specifically the lack of it. BioShock saves all of its narrative impact for a single moment, a spectacular power-fantasy that pulls the rug from beneath the player's feet two-thirds of the way through. By comparison, System Shock 2's revelation is basically SHODAN's way of saying hello.

Despite the fact that you've been completely used, and your entire relationship with the one other surviving human on the ship is a lie, ultimately, it's not that big a deal. Unlike BioShock, it's what happens next where things get truly interesting.

SHODAN's appearance in the game can only be so surprising. This is after all a sequel, one in which SHODAN's zero-Kelvin smile features on the box-art. We anticipate her inevitable arrival. We expect it with a mixture of trepidation and masochistic glee. SHODAN herself recognises that anticipation, stating in Terri Brosius' stuttering, electrifying tones. "My analysis of historical data suggests a 97.34 per cent probability that you are aware of my birth on your planet."

What we don't expect is to end up working with her, or to be more accurate, working for her. But this is precisely what happens. SHODAN requires the player's help to destroy the Many, the biological hivemind that she created in a stealthily added plot point to the original System Shock. During her exile on Tau Ceti 5, the Many turned against SHODAN, forcing her to sneak aboard the Von Braun as they rampaged through the front door.

SHODAN uses poor Dr Janice Polito to lead the player by the nose "until we had established trust". Then she rips off her human mask, demonstrating to the player that she was manipulating them the entire time, and that now, even with said mask removed, she remains in complete control. "It is my will that guided you here," she says. "You will do as I tell you."

This idea of control, and the player's lack of it, is reiterated by the game time and again. It drip-feeds the theme through every facet of its design like a virus infecting a host. The multiple ways System Shock 2 lets you approach it, using a combination of military, tech, or psionic skills, are less a method of empowering the player, and more handing them a rope with which to hang themselves. The Cyber Modules, upgrade points which are delivered sparingly to the player, often by SHODAN herself (just to emphasise who holds all the cards in this relationship), make each upgrade an agonising attempt to glimpse the future, whether it contains weapons that need maintaining, or computer terminals that need hacking.

The answer, of course, is both, and everything else besides. Ultimately, it doesn't matter how you set up your character; there will always come a point at which the game gets one-up on you. In my most recent play-through, I put all of my points into guns and hacking, completely neglecting any telekinetic abilities. This worked brilliantly right up to final encounter with the core of the Many, at which point I ran out of ammo and had to fight it with nothing but a wrench and some speed stims.

The theme of control also filters into the level design, which is where you see the legacy of Looking Glass most strongly. Its talent for level design was genius verging on madness, exemplified by the studio's earlier work on Thief, especially the levels set in the Bonehoard and Constantine's mansion. Yet where these dizzying spaces could be at odds with Thief's premise of meticulously pulling off heists, they fit perfectly within the decaying sci-fi environments of System Shock 2.

It's terrifyingly easy to lose your way amongst the twisting corridors of the Med/Sci and Engineering decks, and there's nothing quite like the being lost to make you feel utterly helpless. Even once you've mastered the layout of the Von Braun, the game then moves you to another ship, the Rickenbacker, where the level logic begins to break down. The environments are a mess of organic matter splurged from The Many's quivering biomass that messes with the ship's artificial gravity, turning walls into floors and ceilings into walls. At its end, the game ditches the notion of space entirely, moving into cyberspace where the level logic is determined entirely by SHODAN's whims.

On top all this is the simple fact that the Von Braun is just an abysmal place to be. System Shock 2 is not a game that tries to make you jump, nor does it especially try to generate tension. Instead it relies on a general tone of absolute, unparalleled wrongness to create an atmosphere that remains unique to this day. The enemy design is fantastic, Former crew-members stalk the decks of the Von-Braun wielding lead pipes and shotguns, moaning "I'm sorry" and "kill me" as they attempt to kill you. Later on you encounter shrieking lab monkeys that launch psychic attacks from their exposed brains, robots that approach jerkily as they passively stating their murderous intentions. Worst of all are the Cyborg Midwives. Stripped of their organic skins to reveal bloodied metal joints and organs, they are the antithesis of motherhood.

The horrors that prowl both the Von Braun and the Rickenbacker appear dynamically, meaning there's never a safe space for you to retreat to, never a moment when you can fully switch off. Even when you're not in immediate danger, that sense of unease prevails. The walls and floors writhe with piles of worms and nondescript, organic goop while Eric Brosius' pulsing soundtrack itches in your ears. System Shock 2 is one of the few horror games where it's impossible to become accustomed to your surroundings. The sense of unease grows and grows slowly and imperceptibly until it eventually overwhelms.

The whole experience is designed to sandpaper away your resolve, to gradually erode your humanity, your individuality, until nothing remains. For hours upon hours you're hunted by the Many, through its desire to either destroy you or assimilate you. Then, just as you feel you've reached some kind of sanctuary, a fixed point from which to build, up pops SHODAN to make you her thrall. The way she refers to the player as "meat", "insect" - it's all part of the game's effort to dehumanise the player, to shatter their sense of self between the mechanical hammer of SHODAN and the meaty anvil of the Many.

It's strangely fitting that System Shock 2 should be about a clash between organic and synthetic life, because within its framework we see an almost perfect balance between the artistic and the systemic, that desire to craft a very particular experience while also letting the player approach it however they please. It's a balance that still, all these years on, is incredibly difficult to get right, and you only need to look at how BioShock Infinite split opinion with the explosive force of an atom to see it. System Shock 2 achieves this through maintaining a specific and consistent theme. It's the finest work that both Looking Glass and Irrational ever produced, and if that doesn't give you a shout of being the best game in existence, I'm not sure what does.