Telling Lies review: flawed but fascinating experiment in storytelling

Their story.

There's a writing technique called cut-up, in which a text is broken down into small component parts and then rearranged, somewhat at random, into a new text. Cut-up has its roots in Dadaism and was used by boundary-pushing artists like William Burroughs and David Bowie. It's sometimes called aleatoric writing, which means there's an element of chance involved in the creative process; alea is Latin for dice game.

There's a sense in which most video game writers are using cut-up technique by default - even when they're trying to construct a linear narrative. As well as scripts, they build worlds and storylines out of huge databases of NPC barks, flavour text, lore snippets and branching conversations. Depending on the game design, there might be no telling when and in what order players encounter these, or whether they encounter them at all. That's where the element of chance comes in.

Sam Barlow, the writer-designer of Her Story and now Telling Lies, is doing something much more intentional, tackling this quirk of the medium head-on with his experiments in interactive fiction. In both games, a film made from Barlow's script is atomised into dozens, maybe hundreds of short video clips, which can then be searched like a database by the player using dialogue keywords. In theory, the clips can be viewed in any order; you could stumble into the denouement with your first search.

Yet the effect Barlow is aiming for isn't some surrealist collage. These are mystery thrillers in which the player is cast as a detective, digging for truth. There's a traditional narrative journey to go on here - it's just that you don't have a map for it.

In Her Story, the video archive you were searching collected a series of police interviews with a single subject. Telling Lies is more ambitious. The archive is larger and of more dubious origin, composed of a mixture of covert surveillance tapes and intercepted video calls. There are four main characters and multiple supporting players.

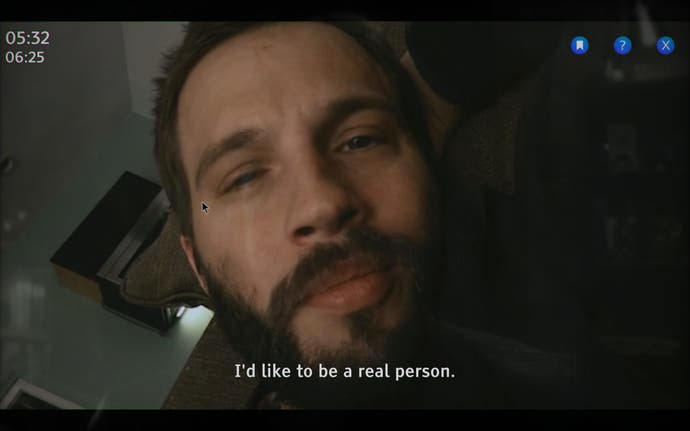

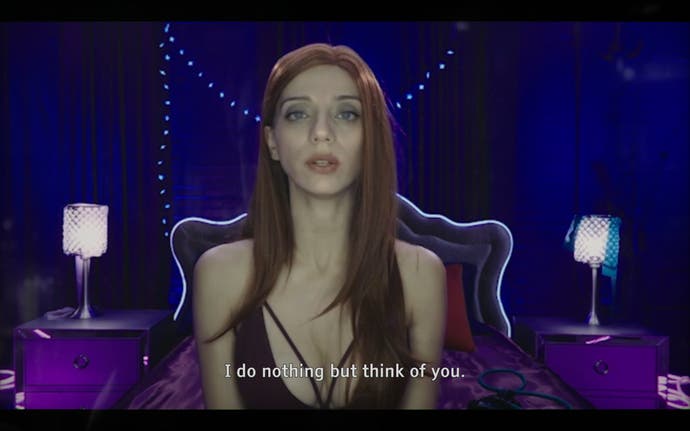

It would be a spoiler to reveal almost anything else about Telling Lies' plot - including the characters' locations and names, since they will likely be key search terms. There's a woman played by Kerry Bishé (Halt and Catch Fire) who works as a doctor, has a young daughter, and is seen chatting to her partner. There's a young, idealistic woman played by Alexandra Shipp (Storm in the most recent X-Men films) who works in a record store and seems to be in the throes of a new romance. There's a cam girl plying her trade on the internet, played by Angela Sarafayan (who had a memorable turn in the first season of Westworld). And there's a handsome man played by Logan Marshall-Green (Prometheus) who seems to be leading some kind of double life.

There is another significant character, played by you. An intro movie shows a woman getting out of a car, entering an apartment and sitting down at a laptop. That's the computer you're operating, and you can see her face dimly reflected in the screen at all times. It's a neat trick, simultaneously dissociative and immersive. Who is she, and how does she relate to these other people? That's just one of the connections Telling Lies wants you to make. A note left on the desktop explains the archive and implies that she only has so much time to explore it before she is "taken into custody". She types in the word 'love' and the first search is returned. The rest is up to you.

Initially, Telling Lies feels very similar to Her Story. A maximum of five results is returned for each search term, which keeps information overload at bay and allows Barlow to curate the clips a little, nudging you gently toward the next term, and the next. But if Her Story felt like peeling an onion, layer revealing layer, Telling Lies is more like untangling a mass of knotted cables. It has multiple strands which intersect, but which also work as discrete lines of inquiry. There's more than one story here, more than one perspective on the 18-month timeline. And there isn't time to explore them all in one playthrough.

This is the major difference between the two games, and it's both structural and philosophical. Her Story allowed you to see how much of the archive you had discovered, and how much there was still to see. This gave you a useful sense of your progress, but also opened the door to completionism: the notion that there was an objectively complete view of the story to be gained, a win state. It was hard, in the later stages of the game, to resist the urge to game the system in your hunt for the last few clips, rather than follow the story to a natural resolution.

In Telling Lies, progress is measured by the clock in the top right corner of the computer screen. Eventually, you will run out of time and have to stop your search; you are given long enough to answer the big questions, but not to answer everything. Your view of events will only ever be subjective and partial, guided by your instincts, your biases, which of the characters you warmed to. Depending on your focus, Telling Lies could be a domestic drama, a spy thriller, a romance or an obsessive psychodrama; it will probably be a hybrid of a couple of these.

It's a more naturalistic approach, and perhaps a more intellectually honest one. It certainly resonates with the game's themes of deception, identity and control, of how we have as many different selves as we have interactions with other people, and of how technology warps human relations. But it has drawbacks. For a couple of hours in its midsection, Telling Lies is quite thrilling, as you start to make connections, as new narrative threads shoot off in unexpected directions, and as you start to perceive the overall shape of the story. But before and after that there are periods of aimlessness - particularly after. Once you think you know the grand design and are filling in blanks, it's hard to know what is expected of you to progress when you don't have Her Story's grid of literal blanks to fill in.

This disconnect is always going to happen if you're trying to tell a whodunnit - or a whoisit, or a whodunwhat - in an entirely non-linear fashion, guided by the player. You're removing the pacing that gives these plots structure and urgency, and replacing it with a kind of organic wave effect, where the player's curiosity crests and then tails away.

Telling Lies can be stylistically alienating, too. The video calls that make up so much of the archive only capture one person's feed, so much of your time will be spent pairing clips with each other to assemble a full conversation. This can be a rewarding puzzle, but it can also make the viewing experience stilted, and it leaves the actors rather exposed. Perhaps it's for this reason - or perhaps it's a lack of experienced direction - that the clips often come off like audition tapes rather than natural performances. I certainly wouldn't blame the cast of talented, likeable, good-looking pros. Sarafayan, in particular, is excellent: her part allows her to explore the performance of intimacy in all its registers, but she undercuts all this with a bruised, steely honesty that's the most real thing in the game.

Barlow has said that Telling Lies was inspired by the freeform design of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, and I can see that in the way it concedes control completely to the player - a particularly brave and generous thing to do with a narrative game. He also likes to mention two classic films as inspirations: Francis Coppola's The Conversation, that masterpiece of 70s paranoia in which a surveillance expert is tormented by a partial audio recording, and Steven Soderbergh's Sex, Lies and Videotape, which views intimacy through a camera lens. You can clearly see the influence of both films and Nintendo's magnificent game. They all play with form. But these are mature, confident explorations of established styles. Telling Lies, by contrast, is but a second baby step into uncharted territory: a little wobbly, a little naive. But definitely courageous and exciting.