Tetris Effect already looks like a classic

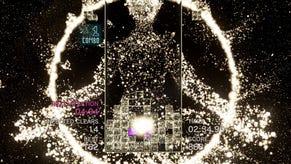

Luminous.

Tetsuya Mizugichi and some of the staff of Enhance Games brought Tetris Effect to our office last week. Martin and I had a go on it - actually, Martin had already been able to play it in Japan, so he watched - and we wrote up our thoughts afterwards. In short, Enhance has a serious banger on its hands. I'm already very excited about this week's demo.

A stellar spin on an all-time classic

Martin Robinson, Features and Reviews Editor

I'm already a little smitten with the output of Enhance Games; this'll be only its third release after the incredible Rez Infinite and Lumines Remastered, and while it's another game that takes an existing classic as its foundation, it's perhaps the small Japanese studio's most ambitious, broadest game yet. First, it takes some chutzpah to take on the almighty Tetris. Second, it takes some serious style and elegance to do it this well.

And what impeccable grace Tetris Effect has. The trappings are vintage Mizuguchi, all star-studded whales, spacey vistas and tinged with a late Saturday night/early Sunday morning spirituality. The embellishments will be familiar, too - the drops are quantised in time with the music, that blissed-out rhythm rushing you along to the zone that's always been at the centre of Tetris and the particular satisfaction it offers, while there's the option for trance vibration that can be mixed out of or isolated down to any one of three rumble tracks. (Enhance takes this synaesthesia business seriously - last month I dropped into the studio's Tokyo offices, just opposite Tower Records in Shibuya, where one half of the space is dedicated to experiments in the field, walls covered in whiteboards and bits of strange machinery including the infamous VR suit giving it the thrilling feel of a lab.)

The surprise, when sitting down to play the final build for an hour, was just how much of it there was, and just how expansive Tetris Effect is. There are modes - so, so many modes - that stretch that familiar foundation out into strange, often fascinating places. So there is marathon mode, ultra mode and master mode, as you might expect, but joining it is a whole new category under the vague 'Effect' umbrella, with sets of variants such as Relax, which does away with some of the punishment of regular Tetris, or Focus, where you can take short, sharp shots of Tetris. Then there's Adventurous, where some of the more outlandish spins reside; take Mystery Mode, for example, where random effects such as the screen turning on its head are dialled in during your session.

It's an absolute explosion of Tetris, and I kind of marvelled that The Tetris Company allowed Enhance to play so fast and loose with the formula. Maybe that's down to Mizuguchi's own friendship with The Tetris Company's managing director Henk Rogers, and maybe it's down to how meticulously planned each new mode is - this is an idea that's been rattling around Mizuguchi's mind for some time, you feel, and something he wanted to make well over a decade ago when he discovered the rights were temporarily unavailable, pushing him along a divergent path that led to Lumines. And maybe there's something in how Rogers, the man credited with bringing the RPG to Japan with Black Onyx, and who was pivotal in Tetris' incredible origin story, now spends much of his time heading up an organisation looking to help establish a base on the moon. Surely he approves of Mizuguchi and co taking Tetris to the stars, and beyond.

A game about memory - how could it be anything else?

Christian Donlan, Features Editor

When Child of Eden was in development, I met Tetsuya Mizuguchi in Tokyo to play through an early build and learn about the game's origins. The best way he had of explaining the difference between Eden and Rez, he told me, was to say that Rez was a game about information, while Eden was turning out to be a game about memory.

I've been thinking about this on and off since playing through a pretty-much-final build of Mizuguchi's latest game, Tetris Effect. This is Tetris, but it's also Tetris seen through the shimmering, distorting mists of memory. How could it not be? We've been playing Tetris for thirty years by this point. I'm forty (somehow), so it's pretty much a game that I've grown up with.

And Tetris has grown up too. One of the weirdest things about Tetris is that you have to reconcile the fact that it's one of those rare easily recognisable classics of design - anyone can enjoy Tetris, and I'm pretty sure that when we finally make contact the aliens will turn out to have their own versions of it - but it's simultaneously a game that has constantly evolved since its creation. Hold pieces, hard- and soft-drops, T-spins, infinite spin! The game we play now most of the time is subtly different to the game that we played on the Game Boy. (Screw infinite spin, BTW.)

Throw in personal memory: all the car journeys, family holidays, school lunch-breaks, migraines. Amazingly, Tetris Effect manages to capture all of this stuff. It captures the sweep of Tetris. I swear it captures the million disparate personal impacts of Tetris. And in doing so it makes it into a Mizuguchi game.

I want to talk in more detail about what that means when I've played more - and it's really not that far away. For now, though, just know that this is, like Tetris on the DS, a game that might best be described as the Tetris Variations. VR is as good as it always is, but the real appeal here is the way that the game takes a classic and reconfigures it in different modes and for different moods. In one mode, you must clear infected blocks. In another, you must occasionally play the game upside down, or pay particular attention to the board's negative space. (Hokusai would be proud.)

Actually, I set VR aside back there, but I will never forget my first go on the Tetris Effect, on the office couch, with the headset over my head. That dark, private theatre world of VR, just me and the board and space whales bursting into sparks whenever I did something clever.

After a few rounds, I removed the headset and, blinkingly, admitted that the whole thing made me feel weirdly emotional. I think I was apologising for the game's power, which is strange in itself, because I was apologising to the people who made it.

Mark MacDonald, a producer at Enhance, pointed out, with exquisite politeness, that it's odd to feel sheepish about this sort of thing. We expect an emotional response from music, art, from pretty much anything. Why not a puzzle game? Proust once went all funny because he had a certain kind of cake.

And with that I guess we're back to memory again.