Tetris Effect review - the eternal puzzler reimagined on a truly cosmic scale

It's all connected.

Timeless, immediately compelling and utterly without mercy, Tetris has always been a game about what isn't there - or rather a game about what isn't there yet. It's a game about the puzzle pieces you don't currently have, and all the stupid stuff you get up to before they arrive. Tetris - the way I play it anyway, forever awaiting that long block - is the story of how you got so hopelessly drunk to fight off pre-party nerves that, once the actual party had started, you had to go home early - and on the way home you fell down an open manhole and broke your ankle.

To put it another way, Tetris, like Hokusai's wave and the FedEx logo, is sort of a secret primer in the power of negative space: over the last 30 years of playing Tetris I have come to recognise the shapes I need to build, and understand that these shapes are, in fact, merely the inverse forms of the pieces I am desperate to receive from the drunken Tetris lords who hang out at the top of the eternal well.

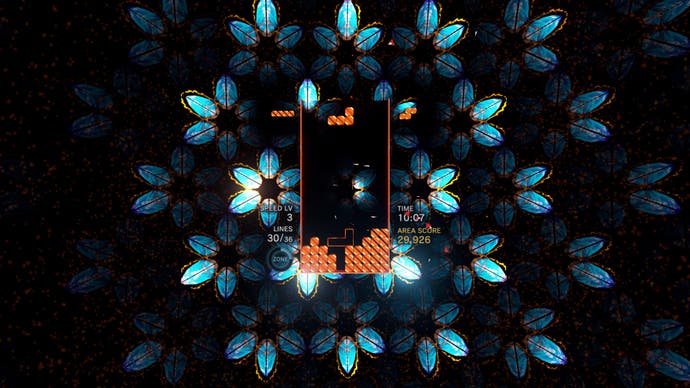

Testify! Now Tetris Effect is here, and as the name suggests it's a game of Tetris that is simultaneously a game about Tetris. It's a deep rumination on Tetris, as well as being a sort of Tetris Variations. It's also the latest game from producer Tetsuya Mizuguchi, whose previous work includes lovely things like Rez and Lumines in which virtual space becomes light and sound, the two bound together so tightly that they are oddly inseparable. So Tetris Effect throws sound itself into the geometry of gaming's most stark and fundamental puzzler. Levels slowly stitch themselves into songs and, like a bat watching the swift midnight world around them appearing through the flighty neon shimmers of echolocation, I suddenly see so much more of what normally isn't there.

For a game that you might suspect would be equally at home with gods or robots behind the controller, what's so life-affirming about the audiovisual elements of Tetris Effect is how much they highlight the embattled human element. Every action in Tetris Effect has a sound-effect reaction. Every twist of a Tetrimino block, every change of lane, every hard- or soft-drop and every clear. What this means is that I can suddenly hear all the strange things I do when I play. Tetris Effect gives voice to my indecision, my uncertainty. In the end-game, it arpeggiates my horrific abuse of infinite spin. Mizuguchi has made a career of exploring synaesthesia, the merging of senses that aren't traditionally directly connected in the central nervous system. For people with synaesthesia, days of the week might each hang at their own height above the bed on waking, or numbers might have their own colours. Games like Rez, like Lumines, give non-synaesthesiacs (that word is a punt, and it comes, again, with my apologies) a sense of the contours of this high-altitude state of being.

But, and I never realised this until now, those games have to take you somewhere new in order to do it. Tetris Effect's fearsome power emerges from the fact that it takes you back to a place you already know intimately, and then it switches synaesthesia on and lets it erupt around you and make the whole thing new again. Whales and mantas flicker and burst overhead, horses and riders made of tiny pieces of light rush through ghostly geometrical canyons, jewels form chains and the chains swing on a tinkling breeze. And even so, Tetris is still, gloriously, a game about what isn't there yet. All this light and noise, all this quick-change artistry, and yet you still lean forward, peering through it, and playing five seconds into the hopeful future.

There's more, of course. If I was forced to describe Tetris Effect to you and I wasn't allowed to mention the word synaesthesia - if we were talking over IM, for example, and I was unwilling to betray the fact that I cannot reliably spell synaesthesia without the help of a spell-checker - I would say that it fixes the only real problem Tetris has, which is that it isn't more like Lumines.

Hear me out. Tetris and Lumines are frequently linked in conversation because they are both games in which blocks fall and in which these blocks must be cleared by slotting them together - and as a result of this, they are also both games that play out across the rugged mesas of your own failures. But Tetris is a sprint and Lumines is a marathon. Tetris gets faster and faster on a smooth, airless curve that slides higher and higher until mortals like me simply can't play anymore. This is efficient, but it's never struck me as being entirely satisfying. At a certain speed, I'm not being undone by own mistakes. I'm being undone by the fact that I simply can't respond to what's coming at me in any meaningful way. I have been bleached out of the game.

Lumines, though, varies the pace throughout, and in doing so creates an experience that you can play and play and play for the length of several charges of a Vita, if need be. This doesn't mean that Lumines lacks challenge, though, because, as you play, the speed shifts around and strange, counterintuitive things happen. Sometimes it's very slow. Sometimes it's very fast and then very slow again. Interestingly, it can be fast and easy: lots of nice clears, the board being whittled down in snappy bursts of decision-making. And it can be slow and very challenging: so many blocks piling up, and then the timeline that clears them just iiiinnches along disastrously.

Tetris Effect takes Lumines' dynamic sense of shifting speed - the playful tangling of Tetris' difficulty curve - and it takes Lumines' ever-changing skins that mean you're playing at the bottom of the ocean one second and playing in the wilds of space the next. It takes all that and provides a campaign mode in which you can play Tetris for a really, really long time. The more you play, sure, the more the trend is generally towards quickness, but this is the pacing of a pop song or an album or a spin-cycle class. A single skin will have an easy section, maybe, and then a middle-eight of intense jerkishness. Then you burst through that and it slows down again. You survived. And then everything changes once more. Throughout all of this you are able to really think about what you're doing and explore possible strategies in a way that traditional Tetris only allows for in bursts. This is open-range Tetris in a manner of speaking: your mind roams.

I did not expect to encounter Tetris with a rangy feeling of any kind. And here's something else I did not expect: I did not expect new private terminology for Tetris at this stage in my life. Maybe I should have. Tetris may have been excavated from maths in a perfect state, but it has never stopped evolving. Hold was added. Hard-drops and soft-drops. T-spins and infinite-spins. And now? Now I think of splits. You know, like in bowling.

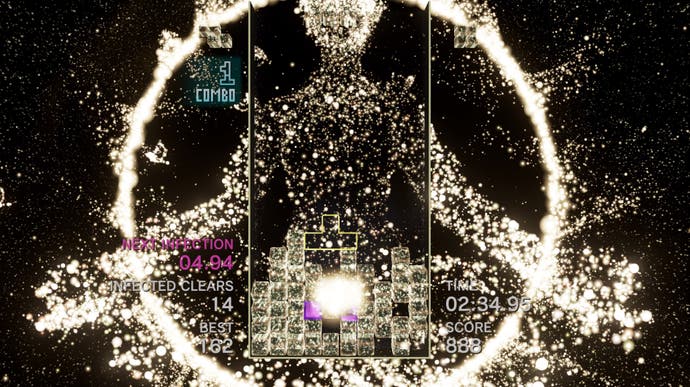

Step back a second. For the first five minutes of Tetris Effect the most startling new addition is the Zone. The Zone builds up through regular play. You clear lines in the classic Tetris manner, and eventually your Zone meter is reaching a happy kind of fullness so you trigger it to mix things up a bit.

Welcome to the Zone! Time slows to a grainy crawl, you feel yourself leaning forward. Any lines you clear in the Zone will not disappear. Not quite. Rather, they will sort themselves to the bottom of the well where they will obligingly stack, and they will continue to stack for as long as the Zone runs. Then they'll clear in one bewildering explosion. Octoris, Dodecratist, Ultimatris! The Zone allows for strange beasts that would otherwise belong to the more outré wilds of Tetris fan-fiction.

It's wonderful, and even better there is learning to be had. At first the Zone is there to get you out of trouble when things get too hectic and teetering. Over time, however, it is used with microsurgical precision, triggered once or twice in a level and sending your points "through the roof". Here's the thing, though, as wonderful as the Zone is - and it's so wonderful I'm quietly miffed I can't go back and rename my first-born in its honour - I reckon the Zone is merely a tutorial of sorts. And what it's teaching you about is combos.

Combos have a history with Tetris, but Tetris Effect, thanks to the Zone, marks the first time I have properly been able to get my head around them. The idea is terrifying in a game, like Tetris, that is ultimately about the big longed-for pay-off of a Tetris-clear. To earn a combo you must clear a line at least with one Tetrimino block and then clear a line with the next too. And then the next, and the next and the next. Each block that falls must clear a line if you're going to keep that combo going - and as soon as you know that the combo exists, who doesn't want to keep it going? So yes, the combos are not new, but the Zone teaches you a perfect way of approaching them, with its rapid, shuffling clears.

Regular play? Regular play feels like a waste now. I am haunted by combos, bedevilled by them. Combos whisper incessantly, prodding me towards over-reaching, towards filling the well with promising gaps, towards dancing on the brink of absolute disaster. When combos are growing, there's nothing like them - I got a seven combo the other day which is probably no big deal for most people, yet I still texted a friend about it. But then I find a line with two gaps in it and the combo must end. A split. Like in bowling. And the combo is suddenly over, retreating back through the wall, laughing.

Elsewhere, you'll find that Tetris Effect has a lot of elsewhere. Outside of the campaign, there are a suite of Effect Modes that break the classic game into interesting variations.

Some of them are strictly therapeutic: you can play games in which filling the well will not trigger the end, just as, once you complete the campaign, you unlock a mode that is basically just a musical toy to enjoy the different skins with. Onward! There are playlists of sympathetic skins. There are modes that offer clearance puzzles that come with a peculiar headshot satisfaction and modes that charge you with getting to grips with the combo system.

But there are also elaborate pranks. There's Mystery mode, in which the board might flip, in which bombs might go off, and in which you may even confront the blasphemy of differently shaped blocks to contend with. These cards, most of them bad but some of them good, are slid in and out of the action as you toil through a brutal Tetris migraine.

Then there are target modes, one in which you have to take out a single block, one after the next, in a battle that encourages you to ignore the rest of the board and forget, as it were, about tomorrow. Another in which clots of infected blocks pop up over time and must be taken out en masse. Hitman and Resident Evil, rebuilt in Tetris, and then a mode in which you build and build around the ghostly shadow of a long block that will fall into the screen only when a timer has run out.

All of these are wonderful - and they all, brilliantly, reprogramme you to play the game in subtly different ways which makes for havoc and wonderful misery as you flip back and forth between them. But they're topped of with some classic takes on Tetris: an incredibly fast mode, a mode that asks you to clear just 40 Tetrimino blocks, a mode that asks you to maximise your score in three minutes, and one that asks you to maximise your score in 150 lines. These are where I have settled for the time being, playing and replaying, and using an outwardly therapeutic game to get very, very angry about everything.

No multiplayer? No explicit multiplayer, certainly, and as anyone who's played Puyo Puyo Tetris will know, that's a bit of a shame. But Tetris Effect doesn't feel like a solo affair when you're scanning the online leaderboards to see who inched you out of the top spot overnight. If any game is likely to bring back the glory days of one-upmanship that defined something like Pacifist Mode in Geometry Wars 2, this is it.

Thinking about it, perhaps I have not missed multiplayer because Tetris Effect is so clearly designed as a single-player experience, a game that longs to get inside your head but has decided, thankfully, not to use a drill. It is an enfolding kind of game: I emerge from play unable to navigate conversations, the colours around me too bright, people speaking too fast. The game seems to know this is the case, which is why it ejects you from even the most overwhelming game with the same kind of fail screen: your blocks, which now fill up the well, becomes weightless at the point of impact and then quietly drift upwards out of view. Breathe!

This solo-effect is doubly powerful when you're playing Tetris Effect in VR. To clarify: this game is a delight on a normal telly. But when you disappear into the public private theatre of the headset, it seems to grow exponentially in power. The Earth on the start screen? You're suddenly suspended above it. And when the skins kick off they burst around you. The opening, undersea one has rocks on the seabed and, if you look up, a distant circle of watery light that marks the rippling surface of some glittering ocean. Elsewhere forests move in close, brownstones crowd you, and lights, everywhere the lights of one transition to the next. It is transporting in the way that only VR can transport you, and it works wonderfully with a game like Tetris, which has a long history of making the world outside the well iris out in your peripheral vision.

One of the things that looms particularly large in VR is the campaign screen, which is spread across a vast image of Laniakea (the Hawaiian translates as something like "immeasurable heaven"), the supercluster that's home to the Milky Way and around 100,000 other local galaxies. Not that I have counted them all. If you were pathologically concerned about your letters going missing, Laniakea is the final thing you would write on the envelope at the very bottom of the address. Ambiguity removed!

It is strangely moving to see Laniakea up there on the campaign menu, its filaments shimmering in gold as the names of levels are spread across its vast arms: Ritual Passion, Spirit Canyon, Turtle Dream. (Tom Waits once observed that "All the doughnuts have names that sound like prostitutes." Tetris Effect levels all sound like the kind of fake head shops set up by the DEA to get trade-in bongs safely off the streets.) Not many games could pull this off, could they? Not many games could justify having a supercluster - our supercluster! - as part of their UI.

But in Tetris Effect it makes total sense. Tetris is a game for the ages, a game that has always felt like some form of universal constant that has been excavated as much as it was ever actively designed. Everywhere in the universe there is complex life to be found I reckon there will be Tetris sooner or later. I hope they get a game as good as Tetris Effect to truly do it justice.