The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn

Pardon my glove.

As a kid, you have might have loved Tintin; as an adult, you probably appreciate him. Hergé's great achievement wasn't just in bringing action and adventure to European comics, but in bringing sophistication, technique and an increasingly cinematic eye along with it.

There's a visual language in Tintin so delicately evolved that you don't even notice it most of the time - the way that faces are caricatured but bodies aren't, the way that a funny little coiled squiggle can effortlessly suggest when a vehicle's in motion, or the way that, in the later books, Tintin (check this out: it's actually true) only walks right to left if he's headed towards some kind of a set-back.

It feels entirely fitting, then, that The Secret of the Unicorn should feel like a victory for technique and sophistication, too - although, with much of the team behind Beyond Good & Evil working on it, that probably shouldn't be a surprise. Ubisoft Montpelier hasn't been graced with the largest budget by the looks of things, but it's worked smartly with it - for the most part - and has found what seems like an ideal video game expression for Hergé's world.

And that expression, it turns out, is the 2D platformer. Unicorn's at its best when you're working your way through Marlinspike Hall, or an Arabian mansion, or even a craggy Brittany castle that isn't in any of the books, clambering up ladders, jumping from ledge to ledge, and tinkering with gentle environmental puzzles.

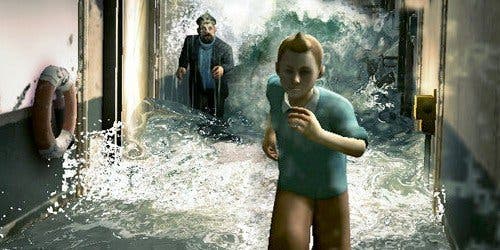

The storyline blends elements from The Secret of the Unicorn and The Crab with the Golden Claws as the search for three mysterious model ships leads the boy reporter into dangerous waters, but the game itself would rather steal judiciously from the likes of Donkey Kong, Metroid, and even, in some of the brilliant co-op missions, Super Mario.

Mostly, it's Donkey Kong, with its scatterings of gantries, its roving low-level threats and its daring leaps and last-minute escapes. The best chapters of Unicorn are a mixture of puzzle mechanics and traversal dexterity as you scope out the territory, work your way into enemies' blind spots, take them out and then open up access to the next area where you'll do it all over again.

It's like moving from one panel to the next. At first, you'll spend a lot of time merely lining up jumps, bursting through switch-plates and stealing keys from guards. As things get more complex, though, you'll have to send Snowy sneaking into gaps in the walls, flap through the sky with a parrot on your back, hit switches with pots or beach balls and even rely on tipsy old Haddock to stand on the occasional pressure plate for you.

Tintin's nimble enough with a nice range of wall-springs, ledge grabs, and forward rolls, and the game's forgiving, too. It's kind with its checkpointing, and generous when it comes to hopping you up onto a ledge that you might just have missed by a hair. The puzzles will hardly pose much of a threat to someone who's tackled Limbo or Braid, but there's a lovely pace to proceedings, and each location's enlivened by a steady trickle of new ideas.

Combat's threaded in with a similar elegance. A mixture of comical stealth takedowns and simple brawling, it eventually gets more tactical once armoured foes, machine-gunners, and enemies that can only be attacked from one side come in. Banana peels, wet paint, and a handful of other elements play up the puzzling aspects of each battle, as do the occasional - and rather repetitive - bosses.

It's a kid's game at heart, so you're not going to be unduly challenged, but there are definite opportunities for flair along the way: taking out a screenful of enemies without being spotted, say, or throwing a lit torch into a shielded baddie who then stumbles into another baddie, who then falls onto a TNT barrel, blowing down a wall that's been blocking your path. At times, there's a welcome flash of clockwork lurking behind the pratfalls.