The allure of medieval weaponry

The sword cuts many ways.

Glaives, pikes, bardiches, halberds, partisans, spears, picks and lances. Javelins, arbalests, crossbows, longbows, claymores, zweihänder, broadswords and falchions. Flails, clubs, morning stars, maces, war hammers, battle axes and, of course, longswords. If you ever played a fantasy RPG or one of many historically-themed action or strategy games, you'll already be familiar with an impressive array of medieval weaponry. The medieval arsenal has had an enormous impact on games since their early days, and their ubiquity makes them seem like a natural, fundamental part of many virtual worlds. These items are based on real weapons that have maimed and killed countless real people over the centuries, but even though we're aware of this, medieval weapons have become estranged and distant from their roots in history. Part of this is our short memory; the passing of a few centuries is enough to blunt any relic's sense of reality. Another reason is they were made a staple of genre fiction. In our modern imagination, the blade has become firmly lodged in the rocks of fantasy fiction and historical drama, and no-one will be able to pull it free entirely. Today, these weapons have been refashioned to serve our very modern fantasies of power, freedom and heroism. There's the irresistible figure of the hero-cum-adventurer who sets out to forge their own path. From Diablo and Baldur's Gate to The Witcher and Skyrim, the fundamental logic of violence stays the same. Battles lead to loot and stronger equipment, which in turn allows our heroes to tackle more dangerous encounters. The wheel keeps turning, and we follow the siren song of ever more powerful instruments of destruction. On the surface, they're problem solving tools, but they also promise the excitement of adventure as well as the power to dominate and enforce our will on those fantasy realms. As such, they become fetishised. Extravagant visual detail and special effects signal a weapon's rarity and power, turning them into ornaments and status symbols.

While the actual violence in such fantasies is often justified by a struggle of good versus evil, the resulting gore and savagery has also captured our imagination. Most games, even mainstream RPGs like Skyrim or The Witcher 3, can't resist indulging in an aesthetic of cruelty and barbarism by showing us the grisly devastation caused by these instruments of murder. Blood spurting from wounds and clinging on blades, heads and arms being hacked off and tumbling through the air, special killing and execution animations captured in glorious slow-motion. Their gruesomeness markedly contrasts with the sanitised, often bloodless effects of modern guns as portrayed in games, disingenuously suggesting that modern violence and warfare is somehow more civilised than that of our ancestors.

Games like For Honor, Mount & Blade, Chivalry or War of the Roses celebrate medieval slaughter with grim nihilism as we hack and slash ourselves through hordes of enemies entirely without any ethical justification. Might makes right, and the means justify the end. The same can be said about the brutal spectacle of the Total War games, whose hordes of clashing soldiers tickle some deep-seated proto-fascist lust for demonstrations of power. These games paint a "grim and gritty" picture of historical violence, the "dark ages" of popular imagination. They're a half-leering, half-wistful gaze into a fantasy version of the past when the destructive urges of our collective Id have not yet been tamed by civilisation and violence was not yet regulated by the moral codes and laws of pervasive state power. In that regard, the butcher and the heroic adventurer use their weapons to pursue the same fantasy: unfettered will and agency, the freedom to follow your impulses regardless of their consequences.

There's a handful of games that deviate from this fantasy. In Dark Souls, for example, the hero is an essentially doomed, perhaps even tragic figure, and the weapons of this world are similarly conflicted, appearing sometimes as mythic, romanticised remnants of a long-gone, more ideal age, sometimes as cruel killing instruments, or both. In Hellblade, Senua's weapons are recontextualised in her struggle against her inner demons as a metaphor for her will to face her illness; a very different kind of empowerment.

What we see reflected in the blade is not the past, but our own desires and preoccupations. People alive in the "age of chivalry", whose weapons we so readily claimed for our fictions, had their own ideas about weapons, what they meant and how they were supposed to be used. One of their functions was to convey social status: sword and lance were a symbol of knighthood, whose members enforced a monopoly on violence. Peasants were sometimes forbidden from carrying weapons, especially those associated with knighthood (see for example Emperor Frederick's Peace of the Land from 1152). The code of chivalry prescribed the honourable way of doing battle, which was idealised in poetry and stories as a one-on-one duel that was first conducted on horseback with lances, then, once one of the combatants was knocked off their horse, on the ground with swords. The victor wasn't supposed to kill the defeated, but to ransom them instead.

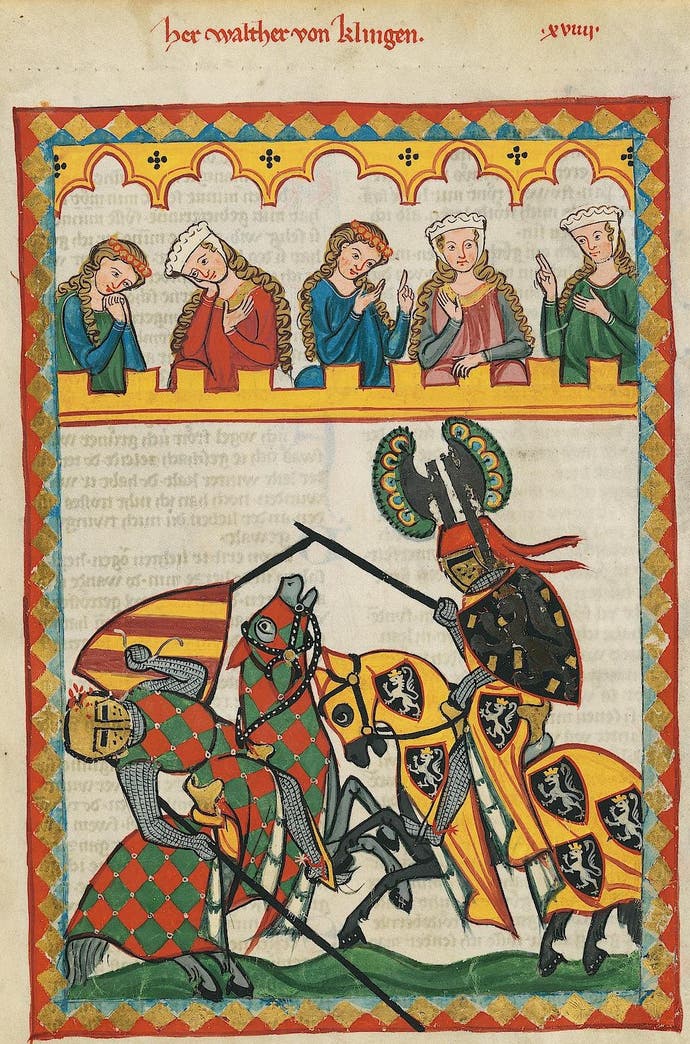

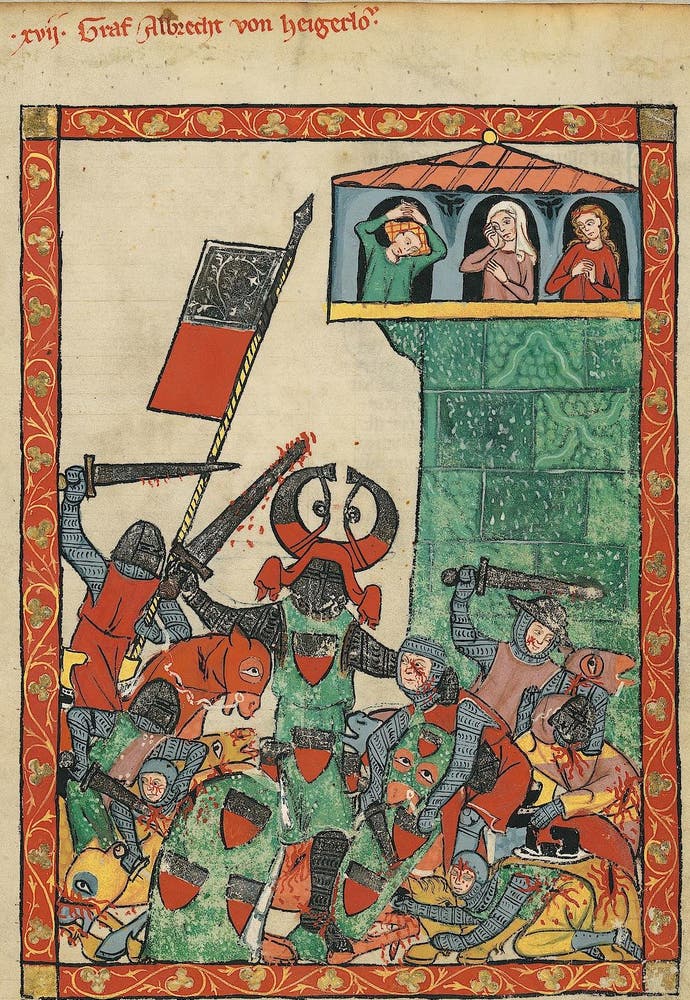

While "real" battle rarely looked like this, these ideals were not just idle fantasies, but were enacted in mock battles such as jousts. Whether in literature, art or reality, these duels were aesthetic affairs: the gleaming of weapons and armour, as well as the splintering of lances were gushed over again and again as highlights of chivalrous combat. The Codex Manesse is a collection of courtly poetry, "Minnelieder" (love songs), from the beginning of the 14th century, famous mostly for the portraits of its poets. Those poets also happened to be knights, and that's the way they're portrayed. Some are shown engaged in peaceful pursuits, but even then, their swords and coats-of-arms are prominently displayed. Many portraits show the poets in battle scenes, many of which follow the pattern of horseback duels with lances. Often, the combatants are being watched by noblewomen. Proving oneself worthy in the eyes of a revered lady was, after all, one of the main reasons that motivated knights and drove them into the thick of the fray (in courtly poetry, at least).

It's hard to say whether some of the portraits are supposed to show real or mock battles, but either way, the thoroughly idealised and glorified depictions and romantic context never exclude bloodshed or even death and mutilation. In one duel scene, a sword seems to have split a knight's head in two, flame-like blood spurting through the split helmet while hand-wringing ladies watch on from above. Another scene shows outright carnage as one group of knights slaughters another, again in the full sight of female onlookers. This comfortable coexistence of courtly romance, chivalrous heroism and bloodlust is alien to us, but was a common state in the literature of the time.

The Morgan Bible, depicting scenes from the Old Testament as if they took place in 13th century France, gives a vivid impression of warfare as it was imagined during the age of chivalry. Many of its miniatures show extreme violence, warriors hacked to pieces, trampled under the hooves of warhorses, or in one case even hewn in halves by a giant glaive. These ferocious spectacles may seem to echo the violence of modern video games, but it is important to remember that this gore appears in the moralising, spiritual context of a Bible likely commissioned by and meaningful to a wealthy member of that same class of warrior-nobility depicted in the miniatures.

While the very existence of intricate art like this ironically puts the lie to the idea of the Middle Ages as a primitive and grim time dominated by constant and arbitrary violence, the butchery displayed in the Morgan Bible makes most gory games seem like kid's stuff by contrast. Unlike most games, there's nothing cartoonishly over-the-top about these depictions. At least to modern eyes, they're shocking rather than exciting, not least because of their historical closeness to actual scenes of medieval brutality. They serve as a reminder that despite their excesses and genre trappings, the fantasies of medieval bloodlust indulged in by so many games are based on real human experiences. Poets and lovers. Heroes and adventurers. Warriors and butchers. The sword cuts many ways, and even though its meanings have shifted over time, it has retained its complexity and ambiguity. Order and chaos, beauty and horror, virtue and cruelty are each two sides of the same blade straddling the less than clear-cut divide between reality and fantasy. The allure of medieval weaponry will likely never go away, and instead adapt to reflect ever-changing desires and needs. If only more games acknowledged that blades are more than a default tool to feel empowered while killing a few hours of one's time.