The Basement Collection Review

"I made my heart into a monster."

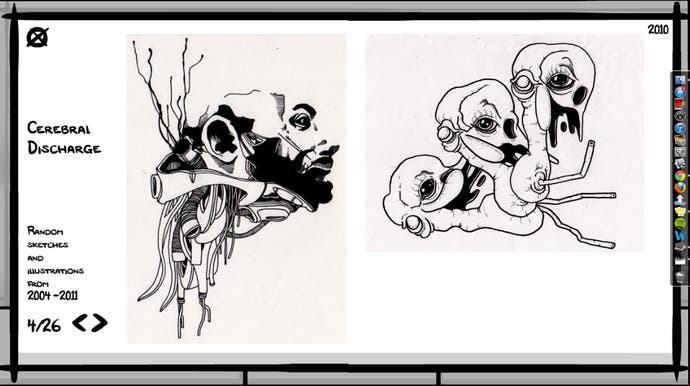

With unlockables that come boasting titles like The Box and The Chest, The Basement Collection is pretty aptly named, really. In principle, Team Meat co-founder Edmund McMillen's latest is a collection of the Flash games he put together when he was learning his craft. In actuality, it's a chance to rummage around through his old files and crates and notepads, checking out everything from design sketches that look like op art and playable prototypes that feel a little like doodles, to a selection of actual doodles and crayon drawings he did as a kid.

It's a bit indulgent, but basements always are, right? They're where you store the stuff you can't quite bring yourself to throw away, the stuff that feels formative. It's fascinating, too. Basements always are. The past isn't a foreign country. It's all so much more intimate than that. Sometimes, the past is a basement.

For anyone wanting to cling tightly to their £2.99, it's worth stating that most of the games here remain available online for free. More than that, they - obviously - still run on Flash in the collection, and they're sometimes a little laggy with it, too. What you're getting, though, is a chance to truly own the games offline, and in a way that you can't when they're just in your browser, and you're getting a certain degree of refinement to go along with them, too. There's a hub menu that manages to be lavish and minimalist - both deftly stylish and pleasantly handicraft - and for each game there has generally been a range of careful updates: new levels and art tweaks for some, fresh soundtracks for others.

Best of all, there's all that stuff from the basement: early sketches, audio QAs, a brilliant selection of music, cutting room floor scenes from Indie Game: The Movie, playable early code, and even a voice simulator for Time Fcuk, which I doubt I will ever tire of using to scare the cats. Added up, it means that, across the package, you get to see McMillen's creative life in full. You get to spend a bit more time with a designer who loves to combine clever arcade-focused ideas with clear - yet dazzlingly overwrought - art to uncommonly atmospheric effect. Tendrils, monstrous insects, endless, waddling homunculi: McMillen is game design's eternal sixth-former, it would seem, with all of the scattered frustrations and wild flashes of brilliance that suggests. (Each game comes with a credit list, too, serving as a generous reminder that while McMillen's a real talent by himself, he's also an excellent collaborator.)

"McMillen is game design's eternal sixth-former, it would seem, with all of the scattered frustrations and wild flashes of brilliance that suggests."

So what about the games? If you're a relative newcomer to McMillen's stuff, the original Meat Boy's probably the obvious starting point. It's not the collection at its best, however. There's no pad support, as far as I could tell - I don't think there is for any of the games - and the keyboard controls and occasional lag make it feel rather primitive compared to its famous big brother. That's because it is rather primitive compared to its famous big brother, of course, and if you're willing to stick with it, it's still a witty and demanding platformer.

It's good, in other words, but if you're after a truly devious running and jumping game, I'd probably start with Time Fcuk. This is a marvellously moody blend of puzzling, dimension-shifting and platforming that boasts a huge randomised campaign wrapped up in a combination of fuzzy monochrome art and typo-littered text that suggests the whole thing is actually an ancient transmission from some nasty far-flung galactic civilisation that has fallen on strange times. There are plenty of all-new levels included, some of which are staggeringly difficult, but the original content is quite capable of standing on its own two feet in the first place. I actually prefer this to Super Meat Boy, but it's a very personal thing: both games are fundamentally different approaches to fairly similar genres, and it's fascinating to see McMillen's depth as well as his breadth. Oh, the level editor's good, too, and it's only my fault that I've yet to build anything that isn't completely moronic with it.

Spewer's another great platformer. This is a strangely sweet game about a funny little tumour fellow who can propel himself around increasingly intricate environments by puking. The fluid physics are fascinating, even if the controls and the sense of inertia both take a little getting used to, but the atmosphere is the real reason to play this, I reckon - particularly if you enjoy the Swiftian thrill of being very small and watching disgustingly large people messing around with your world in the distance. Like Time Fcuk there are new levels to work through here, but be warned: it might just be my computer, but my progress kept disappearing. Ah, Flash.

Elsewhere, Aether is a melancholy delight, if that's even possible. The short sell is that it's McMillen doing Mario Galaxy, with all the squeamishness and nameless horror that suggests. You explore the universe using a gorgeously tactile hook-and-swing mechanic. There are puzzles to solve on each planet you come across, and there's a real sting waiting for you at the very end, too. Amongst various tweaks, the gently monotonous audio of the Flash original is now one of three different soundtracks you can choose from. The new stuff by Danny Baranowsky is great, but the work by Laura Shigihara - the lady that once had zombies on her lawn - is really special. What a lovely, lovely game, as someone or other once said.

What else is there? There's Coil, a short, story-based offering about life, death and tendrils. It was apparently inspired by personal grief, and it's extremely pretty, but it feels like an under-imagined curio compared to the other titles, both too personal to truly connect with and - if this isn't entirely contradictory - also a little too blunt at times.

Tri-achnid, meanwhile, puts you in charge of a spidery sort of creature and gives you control of each of their three limbs. It's far from being my favourite part of the collection, but in a strange way, it's the game that I suspect will really stick with players the longest. It conjures a powerfully oppressive and wearying atmosphere across the course of its short campaign, and the highest praise I can give it - and I mean that most sincerely - is that I don't like it at all.

Finally, there's Grey Matter, a weird spin on arena shooters in which you're a bullet. It's fiendishly hard and the churn is very quick, but it's filled with clever twists, like the ability to trap enemies within triangles, and you get to blow up sperm, so we're all winners in the end. It's also nothing like any of the other games here, tentacle count and mental health preoccupations aside.

Beyond all of that there are two secret games waiting to be unlocked. Spoiler warning: the first of these is a reworking of a satirical title McMillen made very quickly that has proved shamefully compulsive in my house. Additional spoiler warning: the second game I haven't yet discovered. It's presumably hidden somewhere deep within the package itself, or stuck at the end of Spewer, which I am uncommonly crap at. (It's the spikes that do it, I think.)

Even without the full line-up unlocked, I'm still convinced that Basement Collection is a keeper. Yes, it's nice just to actually own these games, even if nobody's ever likely to grip their wife or husband by the shoulders and say, "It's Saturday night, the kids are asleep, the pizza's on order: let's fire up Tri-achnid!" More than that, though, the Basement Collection proposes a lovely approach to a body of work, turning a designer's back catalogue into a playful muddle of boxes and chests where every scrap of material becomes significant to the happy snooper, and a decade's worth of creative toil can be viewed as a whole.

Get in there and start rummaging.