The Binding of Isaac

Randomness is next to godliness.

And man, is this game ever fun. Binding is a bottomless toy chest. Even after playing for ten hours or so - and by the way, those hours are liable to melt away once the game infects you with One More Time Syndrome - I was still encountering delightful little surprises. An immortality-granting cat! A hovering sidekick! Literally explosive diarrohea! Every inch of the thing is infused with McMillen's twisted sense of humor, a cross between Ren & Stimpy and the Necronomicon.

Isaac doesn't move with quite the fluidity and grace of Meat Boy. And, annoyingly, there is no built-in gamepad support. (The settings menu tells you to Google for a homely piece of software called JoyToKey if you want to use a handheld controller rather than the keyboard, which I did.) Still, there's nothing clumsy about Binding. It has studied the masters of the 8-bit console era. It knows how to dance.

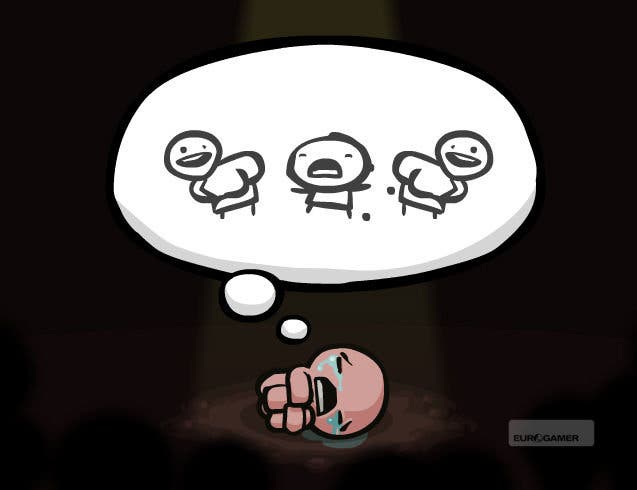

Given the ever-changing terrain, memorisation won't help you much in your struggle to escape Mom/God's wrath. Instead, improvisation is the key. You have to sense what the game is giving you and adjust your tactics based on your best guess of an unpredictable future. And even then, you face the reality that random chance doesn't always play fair. That lack of fairness gets at the core of Binding's greatness.

It's significant that McMillen and Himsl placed God at the centre of their premise, and that they took a Shigeru Miyamoto work as their model. At its heart, Binding is about re-conceiving the role of the creator.

The world of Zelda is crafted to be assiduously fair. Every puzzle has a solution, and there is one key for every locked door - no more, no less. The most difficult fights reap the greatest rewards. And we, the players, know this. On some level, we're conscious of the unseen creator, Shigeru Miyamoto (et al.), who intelligently designed this world as the best of all possible worlds.

Each time you play Binding, you merely get one of the possible worlds. Sometimes you'll find a key for that locked door, and sometimes you won't. Maybe you'll end up with more keys than doors. You could fight a gruelling battle only to win a couple of coins or some useless trinket - not the precious life force you so desperately need. "That's not fair," you'll fume. Yet nobody ever said it would be.

Unlike Zelda, there is no guiding hand of justice. The creator of this world is a laissez-faire type. As a result, there's more of a sense that the game is happening to you right now. When you battle through a tricky dungeon and defeat a giant worm boss with your spider-venom tears and suicide-bomber jacket, there's nothing preconceived about it. You weren't designed to follow that particular path.

Instead, Binding goes like this: A world comes into being, you fight to failure or success, and that world vanishes, never to be conjured the same way again. That uncaring spontaneity heightens the exhilaration of the present moment.

I don't mean to imply that the Zelda framework is inherently inferior. It's just different. And you could say that any roguelike game makes the creator a more distant force, which is true. But Binding's use of the ultra-traditional Zelda template makes the contrast more vivid and exciting.

Binding is not the game I would have expected Edmund McMillen to create in the wake of Super Meat Boy. That was a painstaking, pixel-perfect work - some seriously Old Testament, Miyamoto-esque stuff. In other words, he was a total control freak.

With Binding, McMillen and Himsl created the rules of the world and then set it in motion. Yet this game is nearly as much fun as Super Meat Boy, and more profound. It proves that there's more than one way to make a masterpiece.