The Breakout: A point-and-click game with player freedom

Great escapes?

Close your eyes and let the shapes rise from the mist: the POW camps of World War 2. See the barbed wire, the watchtowers; feel the distant rumble of violence. Adam Jeffcoat, game director, artist and animator at Pixel Trip Studios, spent a lot of time in these camps as a child - in a manner of speaking, at least. Now, as an adult, he wants to go back - and he wants to take us with him.

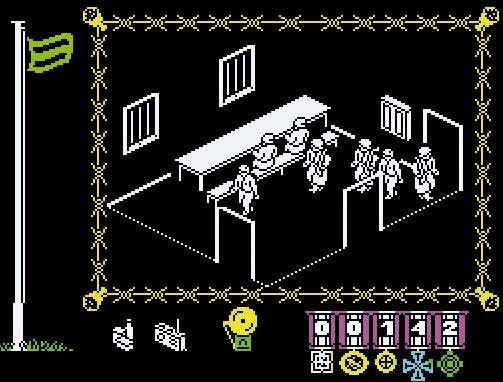

"I was about eight years old," he tells me. "I was around my neighbour's house with their ZX Spectrum playing The Great Escape. All that game consisted of was this really basic isometric kind of camp. You walked around it picking up tools and hiding them." Looking back at it now, Jeffcoat says it's primitive stuff. "But in my head, as a kid, this concept of being in a prison environment where you had to sneak around and collect these tools to escape? In my head it was just insane. It just blew me away, and I think my imagination filled in the gaps."

The camp lodged itself in Jeffcoat's mind as an interesting location for a video game, and refused to shift. Then, one day, he put it all together with point-and-click adventures. It seemed to fit. "You're in this camp with all these rules, and you're essentially under the guards' noses breaking those rules secretly," he says. "You're escaping without anybody knowing about it. That hook really stuck with me."

Now Jeffcoat and his colleagues at Pixel Trip are trying to turn that hook into a game - The Breakout, which has just landed on Kickstarter. It looks wonderful. Using stylised - and inexplicably English - art, all long limbs, quasi-cubist heads and earthy propaganda poster colour schemes, they're telling the story of Guy Kassel, reformed master thief turned RAF pilot. Kassel's plane has been shot down in battle, and he's been brought to one of the most notorious POW camps in Germany - the one where they stick all the really tricky customers, like Steve McQueen and that guy who used to say "Free delivery!" in the DFS adverts. Now it's up to Kassel - up to you - to escape.

And maybe point-and-clicks will be doing a little escaping at the same time. "The thing about point-and-click games is this amazing way they had of being able to tell a story where you were the main character," says Jeffcoat. "Especially LucasArts games. You become the main character and live through these experiences as you tell the story. Why not take that and bring in tension, which is what these games are often missing? Tension and all the other great things a prison break movie has?"

Pinning down where this tension will come from turns out to be rather transformative. "It's quite difficult because there are things like Monkey Island, about exploring and finding things out," says James Allsopp, The Breakout's designer. "The game we're trying to design has a bit more of a sense of motion and urgency. It's a bit more energetic. I haven't come across anything like that yet. I don't think there is one out on the market. If there is, I obviously haven't done my research properly. We love those classic games - the emotional, exploration adventure game - but you never see one that's energetic too. You either get the energy or the exploration, you never get the two mixed together."

In mixing them, The Breakout is going to be a lot more systemically driven than most adventure games. In fact, it's going to be a bit like The Great Escape. "When we sat down to talk about this we wanted to decide, what is it we can do that's different, that's unique?" remembers Jeffcoat. "We realised that the one thing all of these adventure games seemed to have in common - other than one or two - is that you couldn't die. Your character never felt in immediate danger. And there weren't alternative ways to play the game. You all arrive at the same outcome ultimately."

These are the things Pixel Trip focused on. Luckily, the focus fits with the fiction: Kassel's wandering around a camp that has definite rules regarding what he can and can't do, and as he pushes against the limits of those rules, he can slowly start to put a plan together with more freedom of approach than most adventure game protagonists have. He can scavenge the supplies he might need for his escape and he can craft items. "You can combine the items you find," says Allsopp. "In The Great Escape there are tunnels, and they built an air ventilation system using the powdered milk Klim cans they had. We put that stuff into the game."

Preparedness is important - particularly when getting caught sees your supplies confiscated as you head for a night or two in the cooler. Crucially, though, there isn't one set method of escape in The Breakout. "There are numerous escapes available," says Allsopp. "You might try to scale the perimeter fence - we're not saying how at the moment - but then there's obviously a tunnel too. You might escape in a vehicle, even - sneak into a laundry truck, for instance."

"We read there was a real-life escape where POWs built a glider," sighs Jeffcoat, almost dreamily. "A glider! It seems unbelievable. Our rough set-up is that the three main characters you meet in the camp that make up the A-Team - you have to choose which one you work with, and their specific skillset will determine what kind of escape you do. The engineer is more tailored to explosives, the Scottish guy is all about tunnels, and the English captain tricks the guards. This is us speaking idealistically, obviously, but you will have these streams you can go down. It was actually James' idea, right from the start. We have to give you replay value."

"We wanted to put the player in an environment where they can experiment," agrees Allsopp. "Adventures games are often a very linear process, but we wanted players to be able to say afterwards, 'Oh, I escaped via this route with these items.' 'Oh? I did something different.' So that was the replayable value, but also the conversation that's created by the experience, by everyone experiencing a different way that the game comes across to them."

Pixel Trip believes that the benefits of this approach will be reaped in player involvement. "One thing we found was really interesting from the start was the power of putting the player through a really hellish time," says Jeffcoat. "One of my favourite movies is The Shawshank Redemption. What is it that makes that so powerful? It's by putting the main character through such hell, by being tortured, broken down, to an inch of his life. It means that when he finally breaks free, the elation you feel is immense: you feel that as an audience even though you're not even there. So that's what I wanted to achieve with the game. Your character, he gets beaten by the guards, he gets thrown in the cooler, he gets the worst treatment of anyone because he's sneaking around the camp and stealing things, I want the user to feel almost desperate to escape and get out of this oppressive environment, to escape this tension."

Speaking of tension, The Breakout's got about a month - and an admittedly slow start - to reach its funding target of £49,500. And, like any good escapologist, Jeffcoat admits that the team's ultimately pretty flexible about things. The scope of the game will be dictated by how much money Pixel Trip makes through crowdfunding. "We've written the game as a story, you can pick it up and read it as a movie script," he says. "We thought that was the best thing to do so that we had that story as a basis. Then the funding will define what sort of detail we take that story to. We purposefully haven't built any of the camp yet in the game, because the funding will inform the size of the camp."

A cartoon study of hellish conditions. A point-and-click with systemic richness and variety. The Breakout's a tough - and tantalising - objective by anyone's book. Fingers crossed Pixel Trip's up to it. Fingers crossed the team has enough Klim cans tucked away to see it through.

The Breakout is up on Kickstarter right now.