The chaotic tale behind video games' best Lovecraft adaptation

Your appointment with fear.

There's no real shortage of games that draw upon the works of HP Lovecraft. This week's Call of Cthulhu might the latest, but it draws upon another little known but much loved game that shares the same name. Five years in the making, the development of Headfirst Production's Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth is every bit as chaotic, and sometimes as shocking, as the fiction it draws upon.

Based in Sutton Coldfield, developer Headfirst Productions was established in 1998 by the father-and-son team of Mike and Simon Woodroffe. As Adventure Soft and Horror Soft, the pair had had some success in the 80s and 90s with games such as 1984's Gremlins: The Adventure Game, and Simon The Sorcerer nine years later. With a 3D version of that latter series in development, designer Andrew Brazier took to the internet to get feedback on a new idea Headfirst had hit upon.

"I went on a Cthulhu newsgroup in the summer of 1999, as back then it was the easiest way to get in touch with a load of dedicated fans," he explains. "I learned very quickly that the Mythos has a large and very passionate following." The replies were helpful, and varied, offering tips on what should be in the game and even voicing concerns over whether the game should be made at all.

"We had some responses from people who felt that turning Lovecraft's stories into a game was sacrilege. But we knew it was going to be a tough challenge, making something that would interest Cthulhu fans, but also attracting a new audience as well, and ensure the final game was actually fun to play."

Then, in 2000, Mike Woodroffe successfully negotiated the official Call Of Cthulhu license from Chaosium. "It was a great deal," notes Brazier, "because it gave us access to all of Chaosium's RPG source material, which was an absolute wealth of resources." One of Lovecraft's most famous stories, Shadow Over Innsmouth, was selected as the story on which to closely base the game on. "The main reasons for this was the spooky setting, and that it gave us a tangible enemy type in the hybrids and deep ones."

Headfirst Productions was a small studio, with limited resources yet plenty of passion. Woodroffe's original design, a complex RPG/investigation game, was exciting but too ambitious. It was clear, for example, that the NetImmerse engine, while fine for Simon The Sorcerer 3D, wasn't going to be up to the job of portraying the grim and mysterious world of Dark Corners Of The Earth.

"We ended up having to create our own game engine during development," tells lead programmer Gareth Clarke. "Which was crippling for a studio our size. But there weren't any other options at the time." After a number of false starts and team changes, the delays caught up with the developer as publisher Fishtank Interactive was acquired by JoWood, which had no interest in publishing a quirky horror game. After three years of work, the project was on a knife-edge; when Headfirst finally sealed a deal with a pre-Fallout Bethesda, the process took a step back as the publisher insisted on the Xbox becoming the lead platform. "The original version was on PC," recalls Clarke. "We had great big levels that consumed around 256 meg of RAM. When Bethesda signed us up, the Xbox became primary - and had 64 meg of RAM - so we had a quarter of the memory available for our levels!"

Despite the technical difficulties, the Headfirst team still believed that what they were working towards was something special. And indeed 13 years later, what they created remains a remarkable game, quite different from anything at the time, and only comparable to a handful of titles today.

Dark Corners Of The Earth is the story of Jack Walters, a police detective called to the siege of a decaying manor on the outskirts of Boston. After briefly talking with the cult's leader, Walters is trapped inside the building and forced to investigate the area underneath. Here he encounters a horrific scientific device and is exposed to alien beings, sending him into a catatonic state and straight to Arkham Asylum. Upon release six years later, Walters becomes a private investigator and takes on a fateful case: a young grocery clerk has gone missing in the seaside town of Innsmouth and he finds himself embroiled in a mysterious cult dedicated to two malevolent Gods, Dagon and Hydra.

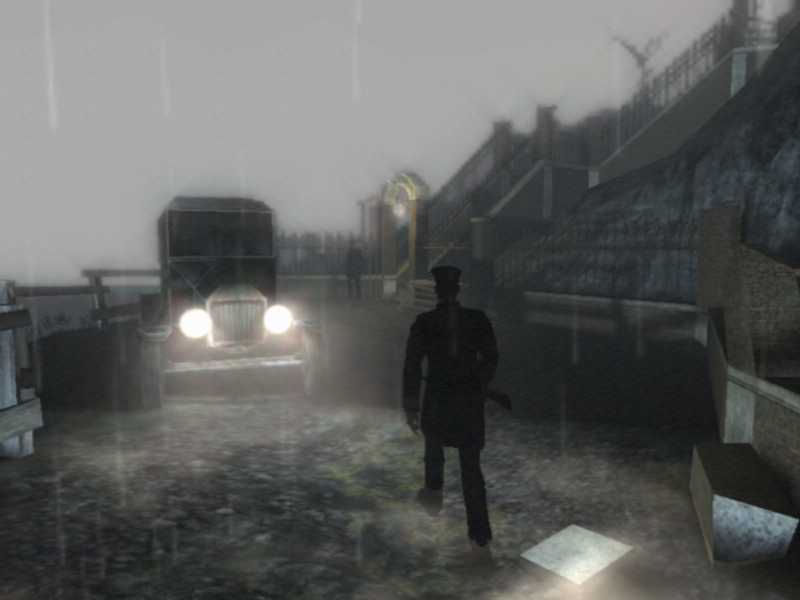

Throughout the game, an otherworldly atmosphere constantly stalks the player as the town's inhabitants grunt maliciously at the intruder. Darkness pervades every inch of the screen, and the first third sees Walters virtually weaponless, and on the run from the town's poisoned and half-breed population. The game is displayed without a HUD, helping immerse you in its world, and presents a number of frantic, desperate set-pieces, most notably a scene in Walters' hotel room shortly after he has arrived at Innsmouth.

Having joined Headfirst in November 2002, Ed Kay was given the task of moulding the infamous scene into something playable. "I can't take credit for the idea, it was one of the first levels built, and a version existed when I arrived," he remembers. "It had gone through several iterations, and a lot of people had touched it before it arrived on my plate - some of whom weren't even at the company by then."

Kay's admission that the level already existed in some form is not to understate his role in the completed scene. "I was given a partially broken, messily coded, fairly un-fun and utterly unshippable mess of a level, and my responsibility was to get it finished in as short a space of time as possible." The use of in-house tools, constructed on a short timeline and subsequently not always up to the job, often meant Kay and the others had to script by hand the behaviour of every single enemy. "And on top of this there were the severe memory restrictions. If I remember correctly, we could only have six enemies active at once - we had to give the impression the whole town was chasing you!"

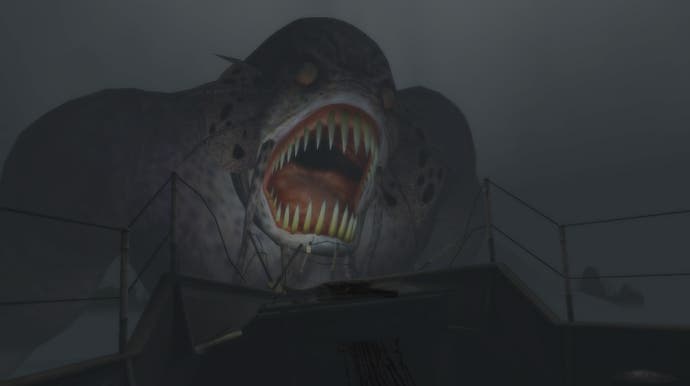

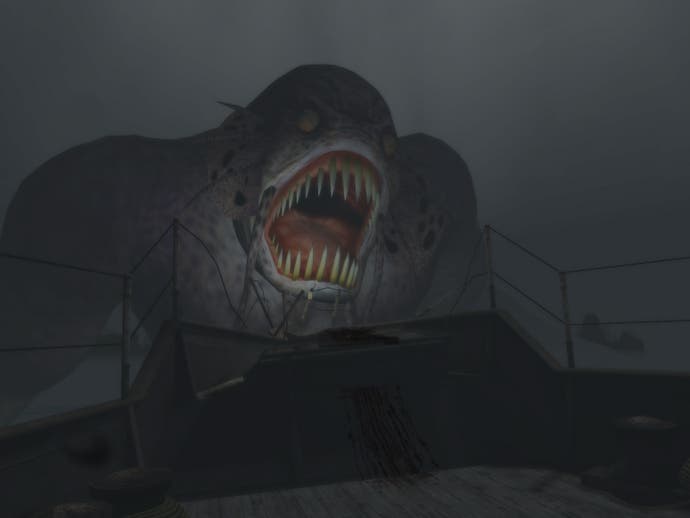

The result was a compelling hunt through the dilapidated Innsmouth Hotel, with the team employing trickery to get the desired tension, as Kay explains. "We faked all kinds of stuff, like gunshots without a shooter, doors banged against with no-one behind them, and so on. The entire level is a total and utter hack of smoke and mirrors." Virtual trickery notwithstanding, it's a triumph of games design. Resting in his room, Jack retires for the evening in his refuge away from the unfriendly denizens of Innsmouth. Suddenly, without warning, the game drastically changes tone as the townspeople become venomous, chasing Jack through the hotel and across rooftops, with the detective having no means to defend himself. It's no easy task getting to safety, as the designer admits. "Looking back, it was just way too damn hard! With a little more experience we would have playtested it more and pulled the difficulty in a bit." Kay and his colleagues employed more tricks in the subsequent USS Urania level; trapped on a boat as first a horde of deep ones, then Dagon itself attack, it's another success of squeezing the last drop out of the Xbox console.

Given that for a large portion of the game its protagonist is unarmed, and that combat is best used as a last resort anyway, Dark Corners employs a stealth mechanic designed to help the player sneak past hostiles. With Headfirst adamant the game should not employ an HUD of any description, even this presented a challenge. "It can only be described as a total nightmare!" exclaims Kay. "The problem was that as you're hiding around a corner, you could literally see nothing - you had to guess where the enemy was going." The solution was to add a 'peeking' system that enabled the player to pop their head round a corner to a relative level of opacity, and a 'soft' level of alert, with enemies going through several stages before finally identifying a threat. "The enemies would also make loads of very obvious signals and dialogue to indicate what state they were in," continues Kay. "Basically we had to use every trick of the book to ensure the player stood any chance of survival." With the only stealth weapon a knife (no poison-tipped crossbow bolts here), there was very little margin for error. "And don't forget that if you got shot in the leg, you were immediately crippled!" notes Kay. A health system based on specific injuries, rather than abstract hit points, added to the game's realism. "It was hardcore."

And it wasn't just the gameplay to Dark Corners that was hardcore. The development for the inexperienced team proved testing, not least the financial troubles that hit Headfirst in 2004 and 2005. "The last few weeks were terrible," laments Kay. "The company was running out of money, but people didn't find out until the last moment when their paycheck didn't arrive. We'd all worked incredibly hard to get the game done, so it was just a punch in the face, and felt so frustrating."

Coder Gareth Clarke was by now working on the PC conversion, which ironically almost didn't happen. "I hadn't been paid for six months," he says plainly. "A few had been in the same position as me, we'd worked on this thing for five years, and couldn't stand it not coming out." Clarke and a handful of others took a gamble that the game would get published and somehow make enough money to save Headfirst. Sadly, the rushed nature of development meant Dark Corners was bugged, especially the PC version, and the delay meant a loss of faith from its publisher. With Bethesda now focusing on its latest instalment of the Elder Scrolls series, Dark Corners was released with little fanfare and reportedly miniscule sales of just over 5000 units on the Microsoft console.

There had been talk, and minor progress, of a sequel. All this and more was abandoned forever as Headfirst collapsed, its employees scattered across developers within the UK and beyond. The pressure of creating a new engine, tools and the game itself on the fly pushed the development into an unsupportable length of time. "Yeah, it took too long to make," notes Kay. "By the time it was done, there were a lot of other first-person games that were much more advanced - Half Life 2 being a prime example." Time had caught up with Cthulhu, yet today, for those interested in experiencing something a little different, something challenging, something, well, esoteric, it's a game worth loading up. "Dark Corners was supposed to be hard, it was supposed to give the player a sensation of how the character's feeling," notes Gareth Clarke. "Maybe we didn't get it perfect, but it was an interesting game because of it."

And perhaps the most disconcerting of all Dark Corners' effects is its sanity meter. While the technique had been used before (most notably in the Nintendo GameCube game Eternal Darkness), here the result of looking at creatures beyond man's comprehension, or spotting one too many eviscerated cadaver, produces a series of consequences rarely, if ever, seen since in a video game. Movement becomes uneven; the screen blurs, causing the player to blink in confusion; Jack's own internal babbling bleeds out of the speakers, the incomprehensible mutterings of a man who has seen too much for his tiny, insignificant brain to process. One step too far and he will raise his weapon to his head and pull the trigger, and there's no escape should Jack be unarmed.

Stoked with the unfathomable power of a mind gone insane, the detective's hands float in front of the player and the screen swims with the fog of madness, as they close around Jack's throat, throttling the life out of the detective in an elongated and pained gurgle. These are the unreal dangers, should we glimpse too much what lives in the Dark Corners Of The Earth.