The classic 8-bit isometric games that tried to break the mould

Head over heels through the years.

The recent release of Lumo has proved there is still much love not just for retro-themed games, but also the isometric viewpoint that became popular on 8-bit computers in the mid-80s. While Lumo's creator, Gareth Noyce, freely admits to the classic Head Over Heels as a major influence, there are many other fine examples of how the genre inspired new gameplay and technological advances back in the 80s.

3D Ant Attack was one of the earliest and most significant examples of isometric games, although it wasn't until the renowned (and mysterious) software house Ultimate released Knight Lore in 1984 that they emphatically took off. Once rival developers cracked how to replicate the overlapping techniques, it was inevitable a swathe of similar games would appear, and most of them added little to the template laid down by the genre's progenitor. The ZX Spectrum in particular was inundated, but there were also many hugely influential and memorable isometric games that attempted to break the mould.

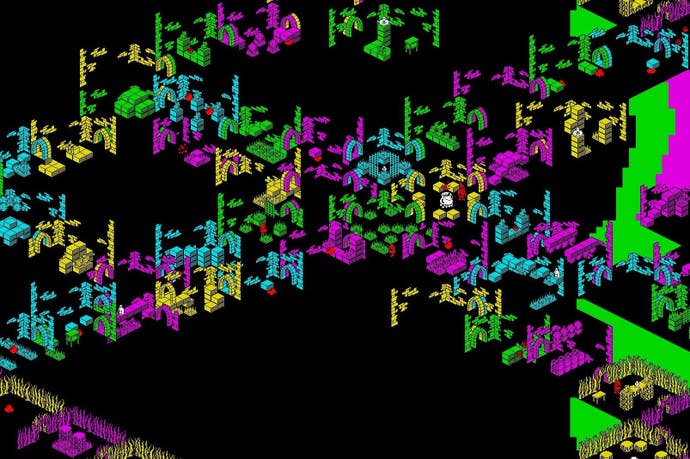

Ant Attack (Quicksilva, 1983)

USP: First major entry in the genre, scrolling landscape

Sandy White and Angela Sutherland's iconic Ant Attack took a basic premise - your partner, male or female, must be rescued from the ant city - and transformed it into an atmospheric and frantic experience. The graphical technique was dubbed 'soft solid' by White, whose chief occupation at the time was, appropriately, as a sculptor. Inspired by the movie Tron, White studied other 3D games that were on the market and set about creating his own world for the story to take place. "The biggest problem was making sure it was fast enough," the programmer told Your Spectrum magazine in 1984, "as some of the mathematical algorithms were really cumbersome." To function as a piece of entertainment, Ant Attack needed to be fast enough to keep the game tense and exciting, and fortunately, after 15 weeks of constant coding, White succeeded. It was just a shame you needed 167 keys to play it.

Knight Lore (Ultimate, 1984)

USP: Amazing graphics, innovative overlapping sprites

It may not have been the first, but there's no doubting the Stamper brothers classic is the daddy of the genre. It continued the adventures of the perennially-hassled Sabreman, who had now become afflicted with a lycanthropic curse. The only cure lay in the hands of an ancient wizard who sat wheezing in the eponymous decrepit castle, and of course there were plenty of puzzles, traps and wandering monsters to impede Sabreman's progress. Using advanced techniques, the Stampers eliminated issues that had dogged Ant Attack (smoothing out the sprites, simplifying controls and the giving the graphics a clearly-defined, almost cartoon look) and created a beautiful game that stunned press and gamers alike. Visually, nothing like it had been seen before, and Knight Lore soon beget a series of comparable efforts, not least from Ultimate themselves.

Movie (Ocean, 1986)

USP: Speech, icon-driven

Drawing on its creator's love of detective stories, Movie was the story of a down-trodden gumshoe, recruited to recover an incriminating tape from a crime lord's office. To help him was a friendly gangster's moll, although the player had to be wary of her psychotic identical twin sister. Movie's theme wasn't the only thing that set it apart; the game's engine allowed its characters to interact with comic-style speech bubbles that were vital in gaining information from NPCs, a rudimentary interrogation element that impressively consumed just 500 bytes of memory. Movie also utilised a novel icon system that, while fashionable and undeniably cool, didn't really lend itself to the style of game.

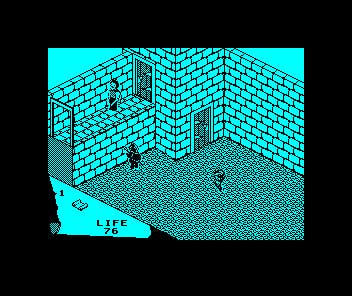

Fairlight (The Edge, 1985)

USP: Inventory management, advanced physics engine

Developed by Swedish programmer Bo Jangeborg, and developed with his own engine entitled Grax, Fairlight was set within a medieval castle, and traipsing around this lovingly-designed map was Isvar, searching desperately for the Book Of Light that would enable him to escape its ancient walls. Fairlight's puzzles often involved skilful manipulation of its many objects, each of which had its own weight and size characteristics. Combat was also key, as Isvar was frequently accosted by the castle's denizens, and there were potions and food to collect as well, making Fairlight an early entry in the action RPG genre seen so commonly today.

Nightshade (Ultimate, 1985)

USP: Scrolling, improved graphics

Alien 8 had taken the predictable step of putting Knight Lore into a sci-fi setting, using the same engine and partially developed at the same time as its famous forebear. When Ultimate unveiled this follow up, boasting a new updated engine imaginatively titled Filmation 2, expectations were high. Filmation 2 not only improved the engine's sprites - adding colour and more detail - but also included scrolling environments. While scrolling had appeared (albeit much more crudely) in Ant Attack two years earlier, Nightshade and its fellow Filmation 2 title, Gunfright, marked another impressive technical expansion of the genre, despite criticism for a lack of significant advances in terms of gameplay.

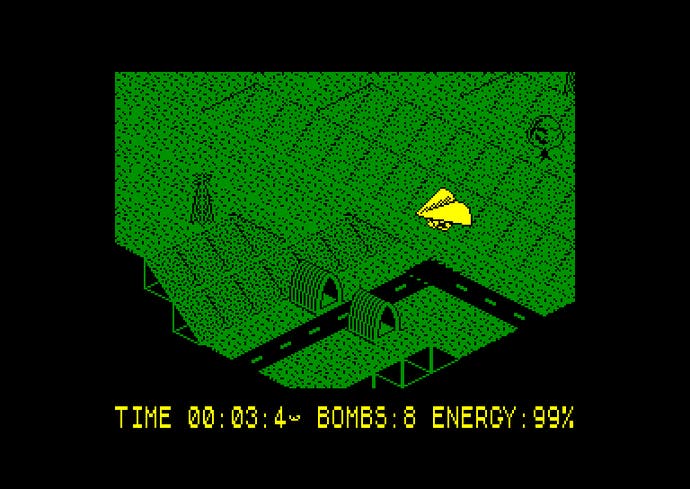

Glider Rider (Quicksilva, 1986)

USP: Use of vehicles

While it may not sit entirely comfortably with some 8-bit fans given the heavyweight company, Glider Rider was undoubtedly distinctive enough to stand out from the crowd. The setting was an artificial island, home to the nefarious Abraxas Corporation. The player could travel efficiently around the island astride a motorbike, but that didn't really help them complete the mission. Dotted around were ten reactors which had to be taken out with grenades. However, these could only be thrown from above after transforming the bike into a hang-glider, a process achieved by descending one of the island's many mountains. Original concept and gameplay aside, Glider Rider boasted a magnificent soundtrack thanks to David Whittaker and was brilliantly designed by Binary Design, aka brothers John and Ste Pickford.

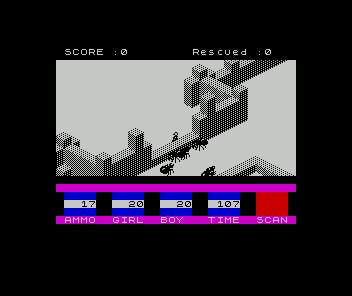

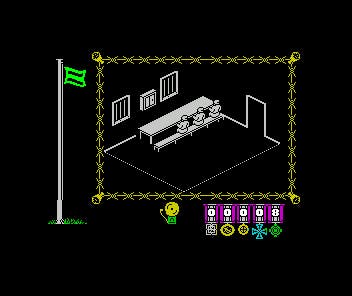

The Great Escape (Ocean, 1986)

USP: Continuous world, superlative atmosphere

The Great Escape was based upon the wartime event, rather than the famous, but historically dubious, 1963 movie. Presented chiefly in stark black and white, an entirely appropriate vision of a German prisoner of war camp, the game featured a combination of scrolling and room-based environments, mixed with a tense and claustrophobic atmosphere. However, The Great Escape's finest achievement lay within its brilliant gameplay. Here was a living, working, prisoner-of-war camp where the guards patrolled incessantly, accompanied by vigilant German shepherd dogs, and every prisoner was expected to be present and correct at daily roll call and meal times. The player was required to follow this routine, while taking the occasional stroll into forbidden areas to acquire items to help them escape, and store them in a secret tunnel. The potential swag included a guard's uniform, wire cutters and chocolate bars, and different methods of escape were possible. Further, the main character's morale was vital; get banged up in solitary too many times and your POW would give up, spirit crushed and content to sit out the rest of the war in glum, hungry despair. Engrossing and technically impressive.

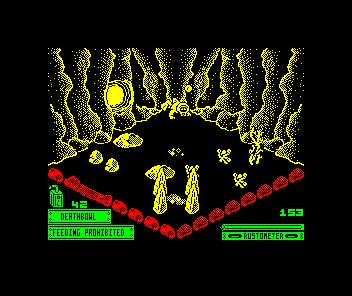

Hydrofool (FTL, 1987)

USP: Great sense of humour, ability to float in each screen

Having already published the isometric comic adventure Sweevo's World, Gargoyle Games produced a sequel which was to not only retain the sense of humour, but also introduce some stunning new environments and gameplay. After clearing up the world of Knutz Folly from the previous game, SWEEVO (Self Willed Extreme Environment Organism, in case you were wondering) found himself in the Deathbowl, a massive aquarium that had become so polluted, the only way to solve the problem was to drain it completely by pulling out four plugs located across the floor. Spread over 200 rooms, and seemingly unaware of the mass nautical genocide his 'cleaning' was likely to cause, SWEEVO needed to solve various puzzles in the isometric tradition. Hydrofool was the first game of its kind to take place underwater, and as such offered a variety of movement not seen before: your character, unbound by gravity could swim up and down, giving the gameplay greater depth. Together with the humour of the original, it added up to another fantastic offering from Gargoyle, or rather, its sub-label, FTL.

La Abadia Del Crimen (Opera Soft, 1987)

USP: Able to control two characters, advanced AI

La Abadia Del Crimen was originally intended to be an adaptation of Umberto Eco's novel, The Name Of The Rose, until the developers were unable to secure an official licence from the author. Undeterred, they kept the setting and rough plot intact and the result was an absorbing isometric game. The player took on the role of two characters, Franciscan friar Guillermo of Occam and his young protégée, and was able to switch between them with a single key press. Upon arriving at the eponymous religious building, the player was confronted by the abbot and asked to solve the disappearance of one of his monks; you were then free to explore, but required to heed the religious services and attend meal times. Failure to do so resulted in a loss of obsequium (Latin for obedience) and, as with The Great Escape's morale, should this reach zero then the game was over. La Abadia Del Crimen's programmer, Paco Menendez, sadly died in 1999, but he left behind a game thick with atmosphere, exceptional artificial intelligence and challenging gameplay.

Head Over Heels (Ocean, 1987)

USP: Two controllable and combinable characters with puzzles to match each character.

Buoyed by the success of their first isometric game, Batman, Jon Ritman and Bernie Drummond combined once more to surpass even that classic. The inspired concept of Head Over Heels was its two main characters, separated at the beginning of the game and each with its own unique abilities. Some puzzles could only be solved by Head; some puzzles could only be solved by Heels. And some puzzles could only be conquered when the two strange creatures were combined. A hub-style gameplay, multiple paths and a wacky sense of humour inspired a generation to fall in love with the gender-neutral creatures, and it remains one of the 8-bit era's finest games.

Notable mentions: Quazatron (Hewson, 1986), Get Dexter (PSS, 1986), Inside Outing (The Edge, 1988)