The Curfew

The game is free. Are you?

Editor's note: In the interest of transparency, we should point out that erstwhile Eurogamer contributor Kieron Gillen and current Eurogamer contributor Simon Parkin were both closely involved in the making of The Curfew, as writer and producer respectively. We've tried to remain as impartial as possible in this report. But we're proud of our boys!

Whenever the "games as art" argument rears its flabby old face, debate usually shifts immediately to the provocation of emotional response. Boo hoo, poor old Aeris and all that. Less commonly discussed is the ability of games to provoke an intellectual response: to make us analyse and reconsider the way we see the world.

That's where "serious games" come in, a rather austere name for a small but growing area of design where interactive amusements are put to use exploring real world issues. Often web-based, and almost always free to play, this is gaming as activism, or at least gaming as an exercise in awareness.

Notable entries in the genre include the BBC-funded Climate Challenge, which presents the multiple compromises and problems involved in tackling climate change on a global level as an addictive resource-management game, and the stark Darfur Is Dying, which, rather naively, uses arcade game mechanics to highlight the horrors of African genocide.

The Curfew is the latest offering in this growing field of games theory, this time developed by BAFTA-winning design agency Littleloud and produced in conjunction with Channel 4, with moral support from the likes of Amnesty International and Liberty.

Set in 2525, it depicts a Children of Men-style future in which Britain is spiralling into totalitarian crisis. Picking up its plot thread in the current recession, the game predicts years of economic ruin followed by a failed terrorist attempt to detonate a nuclear device on UK soil. This is all it takes for the ruling Shepherd Party government to clamp down hard on civil liberties, dividing the British people into Category A and Category B. Those who earn enough Citizen Points make up the first category, and get preferential treatment. Most are stuck in the second category, with few freedoms and a state-enforced curfew that empties the streets at 9pm.

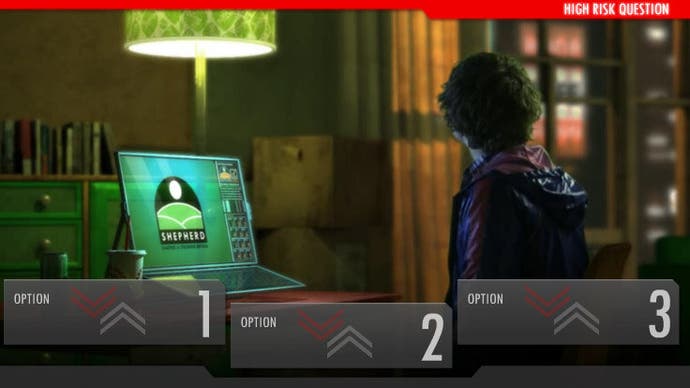

You're dunked into this dystopian brew as a young rebel, recently handed a data packet that could bring down the government and, presumably, begin to roll back the calamitous changes to our society. The action revolves around a safe house: a low-rent hostel where those still outside after curfew can find refuge rather than be scooped up by the police. You've got one night to work out which of four fellow curfew-dodgers to trust with the information you've been given, and also work out how to make them trust you in return.

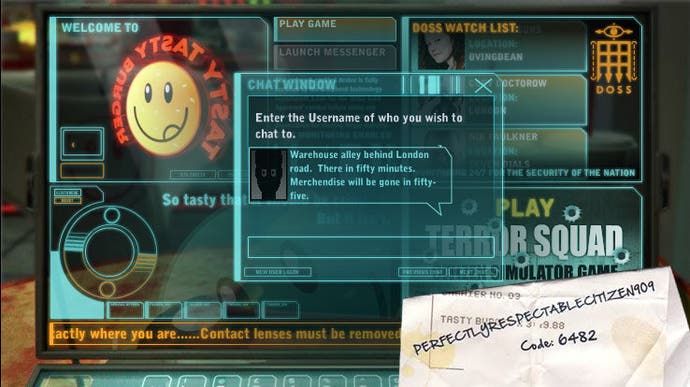

You do this through gameplay that is part point-and-click FMV adventure, part hidden object puzzler. Each of the four characters triggers his or her own sequence of playable flashbacks, during which you discover what led them to the safe house that night, and after each section you can choose which questions to ask. Poor choices lead to a loss of trust, while good observation and shrewd diplomacy can turn a suspicious stranger into a valuable ally.

Hot spots lead to interactions or conversations, while you can make limited use of the latest technology to aid you in your quest. Most notably, you have a phone which can detect "air tags", a sort of wi-fi graffiti that downloads info when located. Holding the phone over the scene, you get an augmented reality view which extrapolates modern day smartphone apps into something more like the magic sunglasses from John Carpenter's seminal satire, They Live. Locating secret images and information apparently opens up bonus lines of questioning, but on the occasion that I managed to find all three bonus items, the questioning didn't seem radically different.

Nor is the conversational meat of the game particularly sophisticated. Frequently you'll choose one reply, only to be sent back to the decision screen to choose another (sometimes contradictory) response in order to get the story back in motion. There are also several occasions where every response leads to the same outcome, an illusion of dialogue that is forgiveable given the restrictions of the web-browser framework, but still disappointing when such interactions form the heart of the game.