The Dark Pictures Anthology: Little Hope review - tension aplenty but not many surprises

Springs eternal?

When I was a boy my dad taught me to play chess. Or at least, I think he did. My memories of these things are blurred by dread; they loom behind me like demons in fog, one QTE away from dragging me under. I'm not convinced my dad is any good at chess but he did have one gambit that always worked on me. Whenever I selected a piece he'd nod, lift an eyebrow and say something like "oh, so you're doing that, are you?" Or he'd sit back, like Caesar regarding a supplicant from one of the meeker barbarian tribes, and ho-hum ominously to himself. After five minutes of this I'd be a quivering bundle of flight reflexes, klaxons howling inside my head as I peered owl-eyed at the board, paralysed by the thought of a million potential reversals. What can we learn from this? Well, firstly that my father is a monstrous bully and it is high time I returned, charged with the lifeforce of a thousand PC strategy games, to exact a humiliating vengeance. And secondly, that my dad is actually a Supermassive game in dressing gown and slippers.

Supermassive games love watching you squirm. If Amnesia is a snake wrapped around your neck then Little Hope - the second game in the Dark Pictures anthology - is a vulture drinking in your movements from afar, counting the seconds till you fall. The horror of these games doesn't really lie with the apparitions that skulk half-seen in the foreground or lurch through the backdrops, never quite committing to attacking you till at long last, they do. It lies with the sense that the game is constantly taking your measure - that every little thing you do or say, every object you pick up or ignore is subject to a terrible accounting.

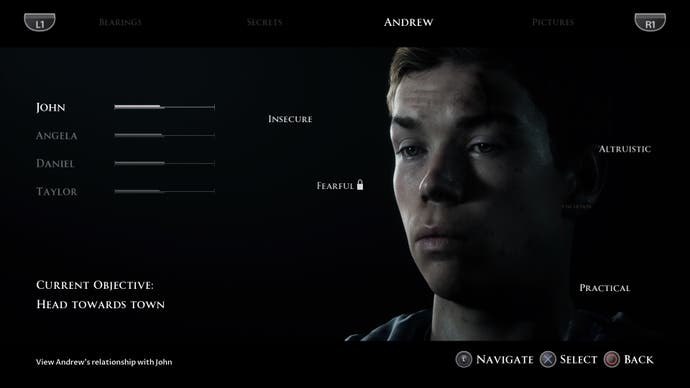

Little Hope puts you in charge of yet another group of bickering, Hollywood-acted lost souls thrown together by supernatural (or are they?) events. As you try to find your way out of the titular town, with its reassuring history of witch trials, you manage the tension between these ill-matched personalities, switching between them at preset intervals. It's possible, as ever, for most of the cast to die without ending the story, and every choice you make is, or appears to be, a weight on the scale. Pick a dialogue option - a calming response to somebody's angry outburst, say - and you'll usually alter one character's fondness for another while strengthening a trait such as "Witty" or "Irritable". Relationships and traits affect the options available to you: should a trait be triggered too many times it'll be locked into that character's personality for good, possibly deciding their fate later on.

Some decisions jolt you more obviously between the rails of the underlying, multiple-ending plot. These are recorded by "Bearing" gauges which resemble astrolabes crammed into skulls by the grimmer variety of Brighton souvenir shop. The Bearing system will note, for instance, that you had dopey good boy Andrew keep a secret from the rest of the gang. It will note that you had Taylor, the obligatory bratty pretty girl, tell stuck-up professor John to bog off when he tried to give her a lecture. And it will always leave you in doubt about whether you've chosen correctly, though there are once again artefacts to find - the Dark Pictures of the title - that bestow ambiguous visions of the future.

The feeling is of having hundreds of tiny pins driven one by one into your flesh. Bearings, trait and relationship changes pop up continuously in top-left like phone spam from Hell. Did it matter that I gave the knife to him and not her? Did it matter what I did to the doll? Perhaps I shouldn't have made her follow him onto the bridge and oh god, we're going to die. We're all going to die, somehow. Presiding over and personifying all these surveillance systems is the Curator, an impeccably English authorial persona who hangs around the murky library that is the anthology's frame narrative, dispensing hints and gloating judgements during chapter breaks. "What could possibly tie all these souls together?" he wonders at you, waving a candlestick. How I hate the Curator. Bet he's good at chess.

All these concepts hail from Until Dawn, and as with the first Dark Pictures game Man of Medan, Supermassive's challenge is to pack that game's unsettling possibilities into a shorter, more economical experience. Little Hope (which can be completed in an evening) does a better job of it than last year's instalment, with traits and relationships tethered more confidently to certain story outcomes. In Man of Medan, I sometimes felt like the swirling character labels were just there for show, like the excess stats or weapon tiers that pad out lesser RPGs. I didn't get that feeling here, but to say more would be spoiling things.

I also found the story more intriguing, though it takes a half-hour or so to find its feet after an electrifying prologue. The game's long night spans several time periods, with characters periodically dragged into the 1600s to witness the atrocities for which the town is known. In the process, you're tantalised with the thought that you might thwart these direful happenings and thus, disarm the demons who haunt you in the present. Except that all of this could be just metaphor, couldn't it? Little Hope keeps you guessing about what flavour of torture chamber it is, with characters often referencing generic horror film plots and revelations in conversation. These in-jokes are seldom that subtle, admittedly. At one point you hear somebody say "this is exactly what happens in horror movies" only to follow up with "those movies are dumb, and I'm going this way without you".

The ending revelation can't help but disappoint after all the speculation, but there are more layers to the mystery this time round: in particular, the thought that you are trapped in a giant theatre production. Sadly, Little Hope itself lacks the stage presence of Man of Medan's ghost ship. There are some great individual elements: streetlights burning red through clawed foliage, a covered bridge that reminds me of John Carpenter's In The Mouth of Madness, a museum with strung-up marionettes. But for all the local history you'll clump together from scattered documents, and for all Supermassive's mastery of perspective and lighting, the game's areas don't really add up into a "place" as such. It's a problem of connective tissue, perhaps: a lot of the time, you're blundering along indistinct forest paths or foggy tarmac roads. Say what you like about Silent Hill, but at least I can tell one end of it from the other.

The action sequences are quite perfunctory, too. The most exciting ones hinge on choosing which character to save - should you have Andrew go to the aid of Angela, who's a little too fond of seeing through other people's bullshit, or John, who's a complete arse but has some sense of responsibility toward the group? Whoever you side with, you'll be hitting prompts to dodge attacks or keep your feet while running away. You also sometimes have the option of hiding, which involves tapping buttons in time to a character's heartbeat. It's all a bit too straightforward for my liking, which isn't something one tends to say of avoiding a spear-blow to the face.

I will always enjoy the atmosphere of rabid self-scrutiny fostered by Supermassive's stories and their supporting mechanics - that sense that to do anything whatsoever is to rap a knuckle against the Sword of Damocles dangling above your head. All the same, it feels like the studio is reaching that Telltale-esque tipping point where the house style becomes - well, not necessarily a weakness, but certainly a collection of tropes in need of deconstruction. It's revealing that while Little Hope's writing is happy to poke fun at movie clichés, characters never reflect on what the events around them share with horror games. After a few hours in Little Hope, you can imagine how those conversations might go: "Hmm, a well-lit door! Let's gather up any and all stray objects nearby before walking through." Or: "Oh hell, I've opened a cupboard like this a few times before - something beastly is going to happen this time, or my name isn't Leon Kennedy."

The latest Dark Pictures instalment is a good Halloween pick nonetheless, especially if you bring along a posse of argumentative and/or squeamish friends. Man of Medan's pass-the-controller Movie Night and online-only Shared Story modes return, and while they're hardly killer features they're worth your time. Movie Night's trick of conferring dubious awards on individual players between scenes is as pleasantly divisive as ever: it turns all those vicious surveillance systems into a source of banter. The next Dark Pictures instalment needs to be more radical, however. If playing a Supermassive title is like playing chess, I feel like I'm the one waiting for my opponent to move.