The game developer, the CIA, and the sculpture driving them crazy

"I work at Langley. I think I can get you in."

Elonka Dunin has been to the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, on two occasions, and on her first visit, she was turned away by a man with a gun.

It was a few months after 11th September 2001, and Dunin was in Washington DC to spend Thanksgiving with her cousin who, due to a home printer malfunction, had narrowly missed a briefing at the Pentagon on the morning American Airlines Flight 77 hit the building. After hugging and catching up on things and visiting the Pentagon memorial, Dunin's cousin asked if there was anything else she wanted to do while she was in DC. Dunin, who works in video game development at Simutronics Corp in St Louis and had never been to the capitol before, thought for a minute before nodding. "I want to see Kryptos."

Although Dunin is now recognised as one of the leading authorities on Kryptos, arranging that first sighting would not be easy. Kryptos is an unusual piece of corporate art and, since the corporation in question is the Central Intelligence Agency, your chances of just rolling up at the gates and getting inside to take a look at it are not high. Kryptos was commissioned by the agency in 1988 for its new headquarters, and the piece was finished and installed in 1990. In essence, it's a large wood and copper sculpture shaped like a scroll or perhaps a flag, with its face divided into sections. These sections contain four stencilled ciphertexts, sometimes known as K1 through K4. To date, the first three texts have been cracked. Only K4, almost a quarter of a century after it was installed in a building that's atypically full of people of the code-breaking persuasion, continues to repel all efforts.

Dunin had heard about Kryptos through her own recreational code-breaking activities, and K4's unwillingness to reveal its secrets was maddening to her. I've spent the last few months talking to a number of amateur cryptanalysts, and they seem strangely affronted by the ciphers that refuse to yield - close up, it's an oddly personal business. All things considered, it was probably worth wasting a day in DC to try and see Kryptos, then, even if, just to get near to the courtyard where it stands, you have to first learn where in Langley the CIA headquarters is actually situated. As far as Dunin could tell, the building had no street address, and in 2001 it was not on many maps. Eventually, she had to work from references to it culled from the directions to a children's soccer game that she had found on the internet: "Drive down the highway, past the exit to the CIA..."

After all that, you still have to gain admittance. That's not easy either. "We figured we'd drive along the outside, maybe peek over the wall and see Kryptos that way," says Dunin when we chat over Skype. "But no, there's no service road, and it's just this large wall, barbed wire at the top, guard shack and armed guards pouring out asking very reasonable questions after September 11th: 'Who are you and why are you here?'"

Faced with guns, Dunin and her cousin decided they would try and talk their way in. "We said, 'Hey, we're just here to see Kryptos,'" she laughs. "The guards relaxed and said, 'Fine: official business only.' We thought, what if we get an invitation from our senator? 'Nope, official business only.' Is there a public tour day? 'No, sorry - official business only.' So: big guys, guns, and eventually we just drove away."

That probably should have been the end of it. Dunin likes to tell people that she has a short attention span - she mentions this three times over the course of our hour-long chat, in fact. It doesn't appear to be true, however. In the days and months following Thanksgiving, she couldn't let the aborted visit to the CIA go, and she kept turning the guards' phrase over in her head: Official business only. Official business only. What she needed, then, was some official business.

Maths runs in Dunin's family. Her father taught mathematics at UCLA. Her great grandfather was the vice-minister of finance for Poland. "I think I have just a genetic predisposition for math," she tells me, and that sounds like a safe assumption. As a kid, she saw the numbers in everything. When she was hanging out at the dime store with all the other kids, she was drawn to the puzzle books rather than the comic books. "I didn't want the crossword puzzles," she says. "I wanted the logic puzzles. Most of all, I wanted the puzzles that had something to do with codes."

As a result, her childhood was dominated by codes - and by a certain persistent streak that emerged early. A neighbourhood friend was a boy scout studying cryptography for a merit badge. "He had some books on codes," she remembers, "so I was always over at his house. 'Tell me about this, tell me about that?'" Finally, he finished his project and gave Dunin all his code books to get rid of her. She continued to tinker playfully with the world of cryptography well into adulthood, but it was only after a trip to Dragon Con in Atlanta around 2000 that she started to make a name for herself in the field.

At Dragon Con, where she was giving a presentation about her work making video games, she fell in with speakers who were there to talk about computer security. One of them handed her a flyer related to PhreakNIC v3.0, a cryptographic puzzle that had yet to be cracked. The way Dunin tells it, she took the puzzle home and - over a weekend stuck indoors with the flu - quickly became obsessed and then solved it. It came apart in layers, apparently. Aside from a confidence boost, PhreakNIC also provided Dunin her first mention of the Kryptos sculpture. A line in the text pointed her towards this weird artwork that the CIA had commissioned back in the late 1980s.

It was codes, then, that would ultimately provide the official business that granted this video game developer access to Kryptos. "Around 2002, I was calling the FBI a lot," she tells me. "I talk to them periodically, since I have a game company so there's credit card fraud I have to deal with. With one of the agents I was speaking to, following September 11th, I said, 'Hey can I help out with the war on terrorism in any way?' He said no. And I kept asking and kept asking, and he said, 'Well, what is it you know about?' I said, 'Oh, I do this cryptography stuff with the hacker scene and there's Uuencoding, ROT13, steganography...'"

I had to look all of those up. Steganography is the name given to the process of hiding a message inside something else - often a digital picture. Blizzard apparently uses the technique to encode Battle.net IDs and IP addresses into screenshots taken in WOW, for example (prior to sending them off to the lizard people who run the world from a base hidden in the hollow interior of the moon). The mention of steganography interested the FBI agent, because shortly after the September 11th attacks, rumours were starting to circulate that al-Qaida might be making use of this particular technique for sending its own encrypted messages between operatives. The local FBI bureau in St Louis felt that it was out of its depth here. Could Dunin maybe brief some agents on the subject?

"The agent kind of thought I was going to give this little 10-minute briefing," laughs Dunin. "But I researched the hell out of it. I put a 70-slide presentation together, covering what kind of codes al-Qaida was using." Ultimately, it didn't seem very likely that al-Qaida was using steganography at all, incidentally: the rumour came from an Italian tabloid reporting on laptops seized by the police who had arrested a cell at the Via Quaranta mosque in Milan. The laptops had a couple of pictures of naked women on the hard drives, leading Dunin to conclude that "sometimes pictures of pretty girls are just pictures of pretty girls." No matter: Dunin's briefing was well received and she quickly started accepting invitations to give the talk all over the country.

"I thought: maybe I could use this steganography stuff as the official business that's going to get me into the CIA," she says. "So every time I would give the talk, I would show some pictures of Kryptos on a slide - one picture that didn't have anything hidden inside of it, and one that did have a secret message hidden inside of it. That's to show an example of steganography and how you can't see the message with the naked eye."

Dunin kept up with the strategy for quite a while. Improbable as this sounds, it eventually paid off. "One day I'm at Defcon, which is the big hacker convention in Las Vegas," she says. "I'm in the roof tent at the Alexis Park Hotel, there's about 1000 people there and I'm doing my talk. Showing these slides on Kryptos. At the end of the talk people come up to me and give me business cards and whatnot. One of them leans across the podium, looks me in the eye, and says, 'I work at Langley. I think I can get you in.'"

They gave Dunin a name and a phone number and - after time spent checking that she was not being conned - she eventually received an invitation to talk at the CIA. An invitation that also covered an opportunity to see Kryptos. "It was great!" she says, describing the building as a typical corporate headquarters for the most part, albeit one with a lot of curved walls to confound bugs and listening devices. Kryptos sits in a courtyard just beyond the cafeteria. "I got to do some rubbings of the sculpture, there was a couple of pictures taken of me, and I thought that was going to be the end of it at that point," she laughs. "I thought, oh, that was great - I got in to see Kryptos, I've achieved my goal. Good! Now I've got games to write."

It wasn't the end of it, however. In fact, it was the beginning of a mission that continues to this day: a mission to see the final section of Kryptos cracked - to see the final message revealed.

Dunin's a natural organiser, so it's perhaps not surprising that she rose through the Kryptos hierarchy so quickly - so accidentally, even. One of the few people outside of the CIA to have actually seen the statue personally, when she returned home to St Louis, she put her rubbings of the stencilled ciphertext online. People immediately started to ask her questions about them, and she was swiftly drawn into the mysterious world of Kryptos fanatics. She co-founded the Yahoo group that still remains a focal point for people trying to solve the K4 text and, along the way, she began to maintain one of the most useful websites covering all things related to the sculpture - a place where people could turn in order to answer many of the questions they might have about this strange corporate installation.

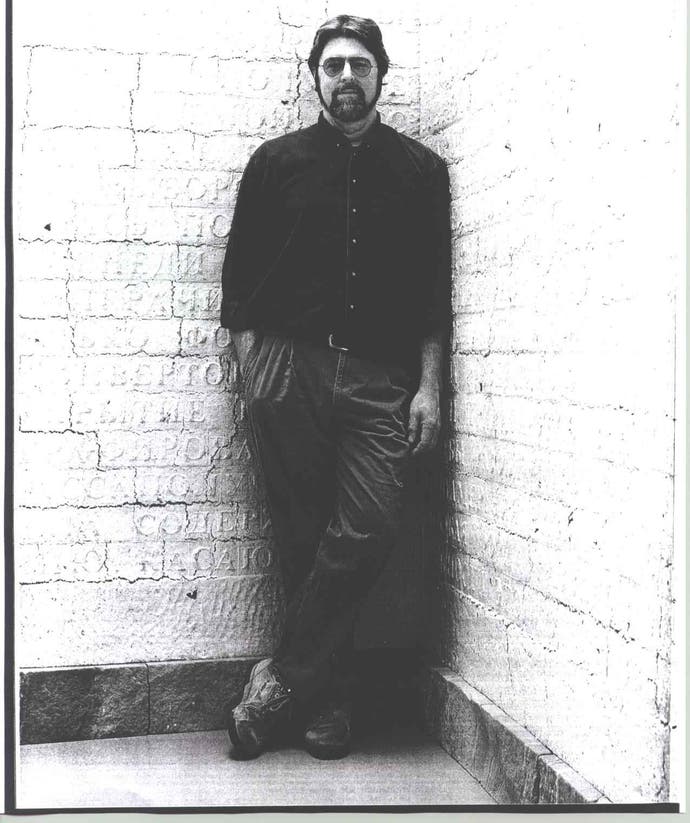

Questions like: who made it? This was an early one, as it happens. "Well, the sculptor Jim Sanborn made it," says Dunin. "Then people asked, 'Well, has Jim Sanborn done any other crypto sculptures?' I said, 'I don't know.'" Dunin contacted Sanborn's agent asking for a list of Sanborn's work. "They said, 'No, that's impossible! Nobody could make a list of everything Sanborn's ever done.' So I thought: okay, here we go again, here's a new goal for me."

Dunin started writing to art galleries all over the country, contacting anyone who had ever shown Sanborn's art. With every connection she made, she would ask if they had an old programme left over from the Sanborn exhibition. Old programmes tend to contain short biographies, and those biographies, in turn, often included the names of other galleries that had shown Sanborn's stuff in the past. The web began to extend. "My apartment's slowly turning into Smithsonian West," laughs Dunin. "I'm posting all this stuff on my website - things Sanborn's done beside Kryptos, and yes, he'd done some other encrypted sculptures." The artist was starting to take shape in her mind. And then, one day, Sanborn himself called Dunin out of the blue and left a message on her voicemail.

It was not the most auspicious of introductions. "'Who are you and why do you have a webpage about me?' he asks," says Dunin. "Since then of course we've met and we're good friends. We've been out to eat, we've been out drinking." (Dunin buys him drinks whenever she can, apparently, "to pump him for information.") "I've stayed at his house, met members of his extended family. I've hosted gatherings at DC which he comes to and which Ed Scheidt comes to. He's the retired chairman of the CIA's Cryptographic Center who taught Sanborn about codes for use in the Kryptos sculpture in the first place."

Sanborn seems as much of a riddle as Kryptos itself - or he's at least a very worthy creator for a sculpture that has sat under the noses of some of the world's foremost cryptanalysts for so long without crumbling. A native of Washington DC, he was born into the kind of mysterious quasi-governmental world that Kryptos plays with. His mother was a concert pianist and photo researcher, his father was head of exhibitions at the Library of Congress.

Originally, Sanborn had intended to become an architect. One day, however, when making a maquette of a building, he realised he would rather be a sculptor instead. His work since then has often revolved around a theme that is frequently referred to as the invisible made visible: codes - information hidden in plain sight - are just one of the ways he explores this idea.

"He's a very tall, very strong man," says Dunin when I ask her about what she makes of him. "Very strong opinions. He gets involved with the topic and then he gets very, very involved with that topic. Before Kryptos, he had never created a sculpture that had text on it of any kind. He'd done some things with engravings and compass roses and magnetism but never anything with text. Then after Kryptos, he did many sculptures that had text. And he did many sculptures that were encrypted. All of the encryption systems that he used through his entire body of work? All of the types used are on Kryptos except for one. Some of his sculptures use binary code, and we haven't found that on Kryptos yet. That may imply that K4 uses binary."

Or it might not. Code-breaking involves social engineering as well as maths: you need to draw a bead on your subject. When Dunin was breaking the PhreakNIC code, she claims to have found out everything about the man who created it, from past girlfriends to the way he decorated his apartment. Sanborn's work should be a rich source of information, in other words, but his interests seem frustratingly wide-ranging. "After Kryptos, he went onto a segment of his work where he was fascinated by the way light was projected onto things," says Dunin. "He went out into the southwest of the US at the middle of the night and he'd beam a pattern of light onto a mountain and use time-lapse photography to record it. There's dozens and dozens of pictures. They look like they're made in computer graphics, but they're Sanborn beaming light on mountains."

Following that, Sanborn became obsessed with atomic history, actually going so far as to build a working particle accelerator in his own back yard. "It was this huge tower, probably about five storeys high," says Dunin. "It had this huge metallic sphere on top, and when he turned it on it would make this huge noise and lightning bolts would come off it. It was - ugh - it just terrified me. You can see it on Google Earth if you were to look at his house. I think he was messing with way too much radiation."

Sanborn's currently working on installations revolving around art that is stolen from Cambodia. "You know, theft and the entire thing of these stone figurines that they'll just chop off at the feet and then ship off," says Dunin. "Sometimes they'll remove the head because the head can be sold separately from the body." Sanborn's actually infiltrated some of the art theft and forgery rings involved: he gets involved, and then he gets very, very involved. "He's putting all of this into an exhibit which is going to be very compelling," says Dunin. "There's one part that I saw in his studio where you see the stone feet and then the body is being lifted by ropes from the feet. It's done in a way that almost looks like Japanese rope bondage."

Despite all of this, Kryptos remains Sanborn's signature work, although that's in a suitably elusive manner, since it's a signature work that almost nobody has access to. Frustratingly, I'm not sure Kryptos really comes across in pictures, either. The scale of it can be hard to judge, and along with scale lies the whole question of the installation's physical presence. Does it look flimsy? Does it have much substance? I ask Dunin whether, after seeing Kryptos in real life, she could even decide whether it's beautiful or not. What's its impact when that curving scroll of copper is right in front of you?

That's a hard question to answer. "Well for me there was so much about the cryptography that I was more interested in the letters than the art," she admits. "It's about 12 feet tall, 20 feet long. I was interested in the way that light was passing through the letters and reflecting off things." She searches around for the right words and then gives up. "I guess you could say I thought it was very striking."

As for the ciphertext itself, although Sanborn collaborated with the CIA's Ed Scheidt to create the code, the actual messages are his own work. It turns out that there's little sense of revelation even here, though. K1 through K3 have been broken for some time, but their contents, once revealed, only seem to enhance the mystery, to sharpen the contrast. The solutions draw you inwards rather than outwards - as does a certain playful confusion surrounding their cracking.

"The first person to publicly solve the first three parts was Jim Gillogly, a Californian computer scientist," says Dunin. "This was in 1999. It made international news." Once Gillogly announced his solution, however, the CIA made its own announcement. "They said, 'Oh we have an analyst who solved those three parts as well - in 1998,'" says Dunin. "'It was just an internal newsletter and we didn't announce it publicly.'" Then the NSA came forward. "They announced, 'We solved those three parts too but we're not going to tell you who and we're not going to tell you when,'" Dunin laughs. "Very NSA. Since then I've found out everything about that group. I knew who was in the group and when they did it. It was late 1992. And then they submitted a memo in 1993."

K1 is the shortest of the messages: "BETWEEN SUBTLE SHADING AND THE ABSENCE OF LIGHT LIES THE NUANCE OF IQLUSION", it reads, and Dunin tells me that Sanborn has admitted this is an original sentence of his own construction. "It was written by him with carefully chosen wording," says Dunin. "That's a very intriguing statement. So why did he choose that? Did he need letters to line up in a certain way or what?"

K2 is longer and stranger. Again, the text was constructed by Sanborn, and it seems written so as to evoke the sense of an intercepted spy broadcast (the WW mentioned refers to William H. Webster, the CIA director from 1987 to 1991):

"IT WAS TOTALLY INVISIBLE HOWS THAT POSSIBLE ? THEY USED THE EARTHS MAGNETIC FIELD X THE INFORMATION WAS GATHERED AND TRANSMITTED UNDERGRUUND TO AN UNKNOWN LOCATION X DOES LANGLEY KNOW ABOUT THIS ? THEY SHOULD ITS BURIED OUT THERE SOMEWHERE X WHO KNOWS THE EXACT LOCATION ? ONLY WW THIS WAS HIS LAST MESSAGE X THIRTY EIGHT DEGREES FIFTY SEVEN MINUTES SIX POINT FIVE SECONDS NORTH SEVENTY SEVEN DEGREES EIGHT MINUTES FORTY FOUR SECONDS WEST X LAYER TWO"

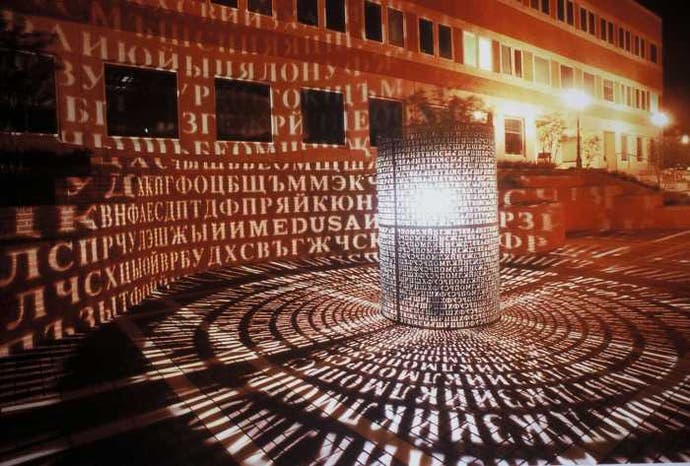

"Now K2, Sanborn says that this is related to the Morse code messages that are other sculptures he placed at CIA," says Dunin. Kryptos, it transpires, is only one of several different sculptures that Sanborn created around the CIA headquarters: the other works include large rock slabs about a foot thick, tilted up out of the ground to look like geological seams. Between these slabs are copper sheets with morse code messages on them. "He also has an engraved compass rose and a magnetic lodestone, and what we call the Triangle Block - it's about a foot in diameter and doesn't have morse code messages or any engravings," sighs Dunin. "It's just very intriguing that it's there."

Also around Kryptos is a pool, benches made of granite and other stones, and a duck pond. "The entire semi-circular garden area that's in the courtyard by the cafeteria was designed by Sanborn," says Dunin, who even went to the General Services Administration to see the correspondence relating to the construction of the installation. "Sanborn's original intent was that as you walked in towards the CIA there would be a series of sculptures with codes, with the codes becoming more and more complex the deeper you got into the building."

As for the co-ordinates mentioned in K2, they point to an area about 150 feet southeast of the sculpture. Sanborn is adamant that he measured the distance very carefully. "Now, what's at that spot?" Dunin asks. "There's nothing there that we found. And Sanborn just gets cagey about it. He says there's multiple levels to the CIA. There's probably office space under there. Maybe he hid something under a ceiling panel?"

K3, finally, is particularly exciting to read because there's a good chance you might recognise the text yourself - it's an edited quote from Howard Carter, describing the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb in 1922:

"SLOWLY DESPARATLY SLOWLY THE REMAINS OF PASSAGE DEBRIS THAT ENCUMBERED THE LOWER PART OF THE DOORWAY WAS REMOVED WITH TREMBLING HANDS I MADE A TINY BREACH IN THE UPPER LEFT HAND CORNER AND THEN WIDENING THE HOLE A LITTLE I INSERTED THE CANDLE AND PEERED IN THE HOT AIR ESCAPING FROM THE CHAMBER CAUSED THE FLAME TO FLICKER BUT PRESENTLY DETAILS OF THE ROOM WITHIN EMERGED FROM THE MIST X CAN YOU SEE ANYTHING Q ?"

For the non-cryptanalyst, this may be Kryptos' most generous trick: as you begin to read, you get that warm rush of recognition. I know this! Carter's talking about the magic of discovery, and if you know the passage in question, you are allowed to experience a little of the cryptanalyst's sense of discovery vicariously. Something that has an obvious context suddenly emerges from the chaos - a signal is pulled from the obscuring noise.

Sanborn had read the Howard Carter account when he was a child and was transfixed by it. He apparently put the text in Kryptos because he thinks that solving a code is similar to the work performed by an archaeologist. "They're both sifting through layer after layer after layer to get to the message underneath," says Dunin. "So many of the things in Kryptos also refer to this idea of layers. Layers and things underground. It all kind of ties together."

It's been two decades since the first three sections of Kryptos were broken. Two decades, during which K4 remains as resistant to cryptanalysts as ever. Could it be that's it's simply encrypted in a vastly different manner to the first three sections? Yes, apparently - although there's probably nothing simple about it.

"Scheidt has said that the fourth part is encrypted in a different way," confirms Dunin. "When we solved the first three parts we had the benefits of the English language, which mean that we could count letters, we could do frequency analysis, by which I mean we could look for letters that are more common than others. That's the number one code-breaking technique that we still use. Even if a code doesn't involve letters - say it involves tones sent from a bank ATM - you still look for repeating patterns. Patterns are what take a code apart."

Unfortunately, Scheidt's said that he removed the advantages provided to cryptanalysts by the English language for K4. "He's said our challenge is to first figure out the masking technique that was used," says Dunin. "What that masking technique is, we don't know. It could be that he removed all the vowels from the plaintext. It could be that the plaintext was converted into binary, ones and zeroes, and then encrypted. It could be like a book cipher, in which the key lies with a specific book. With a book cipher, there are still some patterns, but it would definitely remove a lot of them." She laughs. "Then again, it's possible that he was misdirecting us. He does work for the CIA."

All of which rather neatly demonstrates the problems facing Dunin and the Kryptos code-breakers. They work within a terrifying absence of context. Almost everything is worth investigating. Almost no avenues can be safely ignored.

This must be exhausting. Take the idea of a book cipher. Find the book - and the right section - and you can crack the code with the key it contains. Could the book possibly be right in front of us? Could it be Carter's famous account of the Tutankhamen dig, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen? If so, which copy of that book?

"Ah yes, November 26th, 1922," says Dunin with practised ease. "I think the book itself, I would need to check, but I'm pretty sure it's in the Cambridge Rare Book Library. We've already tried getting our hands on it. It's usually out on loan to one place or another. Sanborn did attend Cambridge, so it's an interesting link. It's possible. It's possible." (The book's actually in Oxford, as Dunin clarified by email after we spoke. Similarly, Sanborn attended Oxford and not Cambridge.)

It's possible. Dunin's echoing Sanborn's stock answer for any and all questions relating to Kryptos when she says that. The problem is that everything's possible. Is a cryptanalyst's life just about disappearing down rabbit holes and not knowing if you're even in the right back garden, let alone that you're following the right rabbit?

"Yeah," says Dunin. "You go down a direction and you say, 'Does this lead anywhere? No? Okay, let's start again. Does this lead anywhere? Oh, wait, that first thing that I thought didn't lead anywhere actually did lead somewhere, I just turned at the wrong junction.' That's a lot of solving codes. It's moving Scrabble tiles around. It's just trying lots of different things and seeing if anything emerges."

So, yes, you could start with books. Or you could start with light. Take K1: "BETWEEN SUBTLE SHADING AND THE ABSENCE OF LIGHT..." Couldn't that be a reference to a time of day?

Dunin and her fellow cryptanalysts have already been there too. "Guess what? It's possible," she laughs. "Sanborn's fascinated by light. We've tried making 3D models of Kryptos and then changing the way the sun shines through the stencilled letters at different times of year. But it's the same thing after a while: even if someone could come to you and say, 'Yes, it's related to light,' we'd still need to know the exact way it's related to that and possibly to K4."

Still, there are clues - even though the clues don't get you as far as you might like. "Sanborn's said that the method he used for part four, it made sense to him as an artist," says Dunin. "Who knows? Aesthetically? It's possible that he took a code system and rotated it 90 degrees, say. We have many videos of him taking a code chart and rotating it. It's one of the things we look at. But again, codes are such that even if I taught you how to solve codes and I pointed you at Kryptos and I told you it uses a Vigenère cipher, a polyalphabetic system with two keys, and I told you what the keys are, it would still be very difficult to solve because there are so many variations of what a Vigenère cipher means. I mean, are you using a cipher alphabet or a plaintext alphabet? Are you starting at the top or are you starting at the side? Of the two keys, is one on the top and the other on the side? It's like those rabbit holes. We may have gone down the right one at some point, we just didn't take the right hop."

All of which raises a fundamental question: what is Kryptos when you get down to it? If it's an artwork, what kind of artwork is it? Where is the heart of it located? In the copper and wood that makes up the sculpture and the stone and water that makes up the gardens around it? In the carving of the letters? In the thousands of hours of time spent by others figuring it all out, or trying and failing to figure it all out? Is this the invisible made visible? Is Kryptos about the human need not just to be, but to know?

Or maybe it's a game. I'm interested to hear Dunin's take on this, given her day job. The part of her that likes codes and the part of her that makes games - are those parts related?

"Yes," she says quickly, and then thinks about it. "Designing games involves creating a set of rules. And codes are definitely operating by creating a similar set of rules. Recreational ciphers are definitely a game. It's a single-player game, and some people would argue the fine points of what is a puzzle and what is a game. To me, anything that's this kind of process of trying to figure something out, you're trying to do it for fun, it has a set of rules and generally a goal? I'd be comfortable classifying that as a game."

In truth, Dunin's work on both games and Kryptos seem remarkably similar. In both contexts, she's a facilitator - a producer in games who ensures that the team's vision gets made, and co-moderator of that Yahoo group focused on solving Kryptos who ensures that everyone has the information they need to pursue their own avenues of inquiry. It's a role she naturally gravitates towards. "I have definitely created games, usually within game jams," she tells me. "Sometimes I've been the sole designer, creator, programmer, everything. But yes, I'm good at producing, I'm good at what we call cat-herding.

"With Kryptos, I do some of my own code-cracking and I know that for most people doing the design is the fun part of making the games," she says. "They wouldn't dream of being a developer if they weren't involved with the design. That's fine. I prefer to say, 'Let me know what you want to do, I'll make sure it happens.' That's what I see as fun. I just go with what I enjoy."

On the subject of making sure it happens, while K4 remains unbroken, the cryptanalysts are making progress. For one thing, Sanborn offered a clue in 2010, revealing that the plaintext for the ciphertext section NYPVTT on K4 is BERLIN.

We're back to the rabbit holes. "We've asked him is that just coincidence? If you were to say something like NUMBER LINE then you would have a BER and a LIN next to each other?" says Dunin. "And he said, 'No, it's the city - it's Berlin.' And the CIA does have a lot of history with Berlin, so that's very plausible. We've looked at what are called cribs: if the word Berlin is there, what would likely be after it? What would be before it? Would it be Berlin Wall? Ahead of it, would it be West Berlin, East Berlin? We've thought of all this because we've been working on it for so long."

On top of that, last autumn Dunin organised a dinner in Washington DC that united, for the first time on record, Jim Sanborn and Ed Scheidt with two of the people who were on the NSA's code-breaking team back in 1992. "This is the first time that they were all in the same room," Dunin enthuses. "It was a dinner at a nice Italian restaurant, I would say total there was maybe 20 to 25 people there. We had some food and at one point, I just said, 'Okay, Ed, we have some of the people who were on that NSA team.' I pointed to them and said, 'You're in the room together. Is there anything you'd like to ask Ed?'

"That room, you could have heard a pin drop," she laughs. "The first reaction was, 'Well, there's nothing I can ask him that he's actually going to answer.' But a dialogue started. There were questions and some stuff Ed would answer, some he wouldn't. He'd defer to Jim Sanborn, and it was just a magnificent conversation that we're still discussing it on our discussion group. It was just an awesome occasion."

Finally, in 2010, Dunin filed a freedom of information request to see the NSA group's notes from the breaking of K1-K3. It turns out that producers can be very useful people when it comes to getting things done.

"I wanted to see their notes and I was told that I couldn't because it was classified," says Dunin. "And I disagreed with that because, why should efforts to solve a recreational cipher be classified? It took about three years of me pushing and pushing and pushing and I finally got a report which I posted online."

That's one victory, at least. So is Dunin feeling optimistic about cracking K4 these days? Cryptography is filled with codes that can't be broken - or parts of codes that can't be broken.

Dunin sighs. "Overall, yes," she offers. "I feel part four will be solved. It's interesting: there's this natural human desire to find patterns in things. We're pattern-finding beings. My firm belief, though, is that Kryptos is not necessarily going to be solved by someone who's this massive big-brained cryptanalyst, because they've already worked on it. I think it's really going to be an idea from left field that comes from a writer, or a gardener, or someone who's a cook whose parents were physicists, or a small child.

"Some people ask me if I want to be the one to solve Kryptos," she continues. "I just want to see it solved. I want it off my plate. If I can help towards the solution process by sharing as much information as possible, great. Absolutely fantastic. I would love to see it solved in my lifetime."

As for Sanborn's feelings? "Sanborn has given different answers," says Dunin. "Sometimes he says that he's just getting too much attention, it's just too crazy. He gets odd people showing up at his doorstep, and he just kind of wants it done. Like any human, he changes his mind day by day, though. Sometimes he says that even after we solve the fourth part there's still a remaining mystery solved, because he thinks that with good art, you should never understand everything that you see - otherwise it's just a waste."

She laughs. "And then sometimes he says he would love to die knowing it has not been solved. To which I say: well, I've got a couple of members of my group who can make that happen!"

You can visit Elonka Dunin's Kryptos website here.