The games industry's response to AI? Reverence and rage

"Now some f***ing website draws better pictures than me."

At GDC in late March this year, AI was everywhere. There's always a buzzword at GDC of course, with the previous years' pandemic-hit shows being dominated by the opportunist grift of talks and stalls dedicated to web3, blockchain, and the metaverse. But this time, amongst the still lingering whiff of crypto-bullshit, artificial intelligence was the talk of the town. And this time it feels different. Where the blockchain chatter was very much a product of new, external parties stepping in to fill the space left by real developers during a quieter year, all the talk of AI was very much coming from inside the house.

Typically it would be worth drawing some context around the recent news in AI at this point, but the reality is that's rather hard to do, precisely because of what AI is. If nothing else, AI as a topic is a rapidly moving target. What was once bleeding edge - remember Twitter's brief dalliance with Dall-E? - already feels old hat. GDC's context, though, was that of a week of developer talks around AI that took place within days of major announcements from AI's biggest players. Microsoft unveiled its GPT-led Office companion, Copilot, on 16th March. Google announced something that sounds rather similar on the 14th. On 15th March, Midjourney, one of several viral AI image creators, introduced Version 5 of its tool, which is able to overcome some AI image generation's earlier struggles, like celebrity faces and regular-looking hands.

.png?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

For some illustration of the speed of change here: by 30th March Midjourney had paused signups for free trial users because of "abuse" of the system. Its creators explain this as being down to a surge of one-time users responding to a viral how-to in China, that combined with a temporary GPU shortage and caused it to crash - not, they emphasise, all the (fake) viral images of Donald Trump being arrested and various other celebrity deepfakes that started doing the rounds. (It also banned various prompts that might lead to "drama", although the Verge noted there are easy workarounds here, such as the "Donald Trump being arrested" prompt being banned, but "identical output" being possible with "Donald Trump in handcuffs surrounded by police.")

Just last week, the European Union proposed its first AI copyright regulations, which would require companies using generative AI programs, such as ChatGPT, to disclose any copyrighted material used to generate its output.

At GDC itself meanwhile: at least 20 talks dedicated to AI - that's excluding the other AI, as in, the one describing non-human opponents you encounter in games that we also, confusingly, refer to as AI. Although there is some overlap there too. Plus, relatively major announcements from the likes of Unity about AI tools, and all sorts down on the physical show floor. At a glance, it means shows like GDC can present a fairly unified stance from the industry: AI is here! On closer inspection, we've seen that before - see Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella's pronouncements of mixed reality's arrival in 2019, the metaverse's in 2021 and AI's this January, for instance - and more importantly, it's just not really what the industry thinks. Largely because, as one person put it, AI is not a "monolith" to be considered as one singular thing. But also because neither's the games industry itself. The real reaction was as wide a mix as you could get. On the one hand: packed-out talks, glib company lines and a cultic kind of reverence. On the other: scepticism, disdain, and outright rage. And all manner of opinions in between.

The most obvious sign of AI's "arrival" this year was one specific talk: The Future of AI in Gaming, a panel sponsored by Candy Crush developer King, featuring the company's chief technology officer Steve Collins and Candy Crush's head of creative Paul Stephanouk, plus speakers from Sony, Unity, and Level Up Games. Long before the talk was due to start it was packed out to fire code capacity, with attendees lining the walls of the room - I got there myself a good 20 minutes beforehand and it was already full. More bizarrely, scores of attendees who couldn't get in and knew the talk was completely full actually stayed in line, for the duration of the talk, in the hope that dozens of people ahead of them might leave early and vacate a spot.

Speaking to Eurogamer after the talk, Collins explained the studio's stance in more detail. Its ambition is to pivot to being an "AI-first company," he said, in the wake of its acquisition of Swedish AI company Peltarion in mid-2022. The way King uses AI now is primarily for testing - a theme which came up a few times across speakers and interviews but in King's case is specifically a question of scale. Candy Crush, he explained, effectively alters its levels to be bespoke in difficulty for each individual player, and at the scale he mentioned - "230 million monthly players" and now over 13,000 levels - AI is really the only option. "It's really hard to do that if you don't have a million players playing the level all the time in your back pocket." What the AI does in this case is essentially "play those levels as if they were a human player".

"We can't have an individual tester per player, we can't have an individual level designer per player. So in the analogy, in order to get down to that level of an individualised player experience, we'd have to have millions of designers and millions of testers - that's not even remotely feasible. That number doesn't even exist in the world. So this is why we use automation increasingly."

"It's a tool that's in the hands of our designers." - Steve Collins, CTO, King.

But, he said, echoing another theme of conversation around AI in games, it's a "tool" that's "in the hands of our level designers and our level testers, so they use that to augment what they're able to do in those spaces". Designers at King "use AI in order to initially design a level, tweak the level, and get it to where we want it to be, and then our testers come in, and they use AI to really shake the level out and see if it does exactly what we want it to do".

Microsoft's approach, at least according to its own also-sponsored talk, seems to be similar. "Our QA teams have been using scripted, automated bots for testing for decades," said Kate Rayner, technical director at Gears of War studio The Coalition. "They've been exploring embracing AI tools to see how it can empower them to do more." She described AI's implementation as "power tools for artists," and suggested it might be used for combatting cheating online. Examples include Microsoft's use of AI to dynamically adjust the skill level of non-human opponents who fill in when players drop out of multiplayer games and, on the QA front, a means of discovering previously undiscoverable bugs before games launch - much the same as it's currently being used by King.

Haiyan Zhang, general manager of Gaming AI at Microsoft, made similarly optimistic points, describing her role as working "in a very complementary way" with Rayner. "I sort of visit studios and I say, 'Hey, what sort of custom AI models and algorithms are you working on?' Because we have a fundamental belief that AI for games is best innovated with and within the game studios."

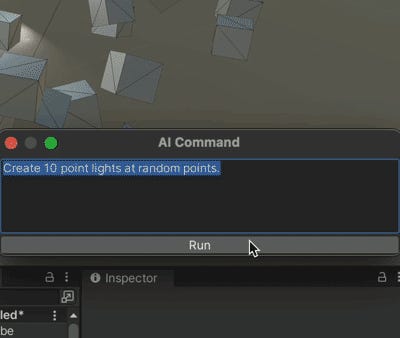

"We're really using Xbox Game Studios as a testbed to think about new tools for the entire industry," she added, pointing to what she called a recent "surge" of "exciting prototypes, exciting hacks on Twitter, on social media". One example she gave was a proof of concept created by Keijiro Takahashi, a developer at Unity, who added ChatGPT integration for natural language prompts into the engine, enabling users to create objects and light them by using simple phrases like "rotate 'cube' game objects randomly".

As Takahashi puts it on his GitHub page, in answer to the question of whether it's practical: "Definitely no! I created this proof-of-concept and proved that it doesn't work yet. It works nicely in some cases and fails very poorly in others. I got several ideas from those successes and failures, which is this project's main aim."

Zhang also took several moments to emphasise the "huge opportunity" AI provides for improving accessibility and inclusivity in games. "How can we enable players from different cultures to talk to each other in a seamless way? How can we make sure that our games can be played by players with differing abilities to come along and play in an even playing field?"

Ultimately, and somewhat inevitably, the mood at Microsoft's talk was one of unanimous positivity, with Rayner describing AI as a whole as "just raising the bar across the industry" and Zhang driving home the point. "Someday we're going to see higher quality games, through using AI tools. It may not be today, but maybe tomorrow... [bringing] completely new experiences that players haven't seen before".

Between these talks, things were rather different: a mix of everything from cautious optimism and balanced curiosity to something closer to disgust. Jeff Gardiner, former producer and project lead on Bethesda's Elder Scrolls and Fallout series, now founder of his own studio Something Wicked, told Eurogamer that AI will likely be "an incredibly useful tool, especially for searching, or for research, or for figuring out problems... I think it'll be an incredible helper in terms of certain things."

But Gardiner also harbours concerns. "I do believe that, on a very fundamental level, it could hurt creativeness," he continued. "I don't like the fact that AI is scrubbing the internet stealing art. It actually bothers me to the core. As soon as I found out it was doing that I ceased and desisted using those tools myself personally. It's not cool."

"I do believe, on a very fundamental level, it could hurt creativeness... It actually bothers me to the core." - Jeff Gardiner, founder of Something Wicked games.

Paweł Sasko, quest director at CD Projekt Red on Cyberpunk 2077 and lead designer on The Witcher 3, is less concerned with the risks of AI and broadly a little more optimistic, in part because when it comes to replacing artists, he feels AI just isn't good enough at doing their jobs.

"The thing is, I do - like a lot of game development studios right now - a lot of 'R&D', sometimes using external partners, to see how we can use that AI in our work to actually speed us up," he explained. One of the areas where CDPR is already seeing quite a lot of "potential options" is in "everything connected to graphics", for instance when it comes to something like "early concept art, and early examination of those fields".

"AI is a tool. It will be really wonderful to try to like, scope out possible directions where you could take in your game, and try really different things. Because we as artists, every one of us is a sum of what we have experienced, what we have consumed, what we think, and this is what our output is. AI can have so much more of that output. Therefore, you can actually produce and open so many more doors."

Using it for that period of "idea generation, opening doors and so on", he said, "it can actually be much more varied, it can actually lead you to places you wouldn't go before. So I think this is actually pretty useful."

Regarding a second possible use - "ChatGPT... everything connected to text generation" - Sasko was less optimistic because, in his view, the technology just isn't up to it. "There's already been a lot of work going on in the majority of big companies, [who] are trying to figure out how to actually use AI here as a tool on the writing team." Games like Mount and Blade 2, which already has an AI mod in place where the player can 'talk' with non-player characters, were an example of this in his view.

"You can see it and you can see that the writing provided by Chat is pretty bad," he continued. "It's really not up to par with the quality, really, in any way. So it's not really suited for that." A better use for it in his opinion would be 'combat barks', the short lines where NPCs respond to player actions, where Sasko suggested you can effectively "draw a circle, from where it should take inspiration" with very specific lines for an AI text generator to be fed.

A third place where Sasko told Eurogamer it's been considered, perhaps most controversially of all, is in voice acting. "Since like 10 years or so ago we as an industry have adopted voice generation tools," he explained. So far this has been the "robo-voice, basically reading us stuff so we can hear the scenes before [human voice recording] actually happens", much like how a director might block out scenes with stand-ins instead of actors.

Only now, examples of voices based on celebrities or voice actors are already showing up. "Of course," he went on, "that still needs to be regulated, right? It's almost like stealing someone's intellectual property. Like, when we are just taking and copying someone's voice... I think this has to be regulated properly, the voices will need to be properly licensed, so that they can be actually really used, in a proper way."

Still, for CDPR there might be some clear benefits. Voice acting is "one of the most expensive parts of the game". Bringing in actors to scope out scenes or record them is a process "taking so much budget, especially when you're doing as we are doing, when you have stars, like Keanu Reeves, Idris Elba, Sasha Grey, all of those actors - and in all the other languages we also have so many prominent actors that are also expensive, right? In that situation, the voiceover is such a big part of the budget, having an AI to kind of support us and provide the first version or even patch up some lines that were mistaken, or patch up the lines that had to be changed last minute, is such a great help".

"But I want to emphasise here that with all of these three applications, I don't think it's going to replace artists, writers, voice actors in any way. I cannot see it happening, at least at this stage. Maybe in 10, 15 years. It is developing really quickly. But with that really quick development, we can already see its downsides. Like, for instance, Midjourney is not able to handle many different styles; you can really very quickly see its style, it's very distinct when you see it. And the same goes for voices, the same goes for chat - you know, those are, for me, just tools."

Away from the quiet of the back rooms where I spoke with Sasko, Gardiner and Collins, up on the third floor of GDC's main north hall, in the final session of the multi-day Animation Summit, a different kind of noise filters down. An angsty, defiant wave of standing ovations, yells from the crowd, a synthetic drum beat and jagged strums of a guitar. Ryan Duffin, Animation Director at Microsoft-owned State of Decay developer Undead Labs, has finished the final talk of the summit and, filling in for a last-minute dropout, has prepared a song.

"I don't think it's going to replace artists, writers, voice actors in any way. I cannot see it happening, at least at this stage." - Paweł Sasko, quest director at CD Projekt Red.

"I'm not a machine, and I earned an art degree," goes the cold-open chorus, "but now some fucking website draws better pictures than me..."

Duffin's talk, just before the guitar was ominously whipped out, was originally titled, Exploring the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Feedback Culture in Game Development: Lessons Learned and Future Opportunities. That title, he said, was actually "bait," the real title instead: Nothing Really Matters: Negativity, Criticism, and the Machine That Will Destroy Us All.

"I started thinking about the zeitgeist of 2023," Duffin explained, and "two things jumped out at me: AI, and feedback culture. It's worth mentioning I am not an AI expert, if I say anything insightful here, it's regurgitated from people who are smarter than me".

"However, the removal of the need for human expertise is thematically appropriate when we're talking about AI, because it makes no secret about that trajectory. The discourse among professionals and professional creatives seems to be either angry shouting that this shouldn't exist, or casual acceptance that it's just another tool on the inevitable march of progress. Whether you think it should exist or not, it does. And yes it's a tool, but its advocates have made no secret that 'democratising' is a nice-sounding word for cutting out experts like us."

Duffin's link between the two "zeitgeists" of the year essentially lies in the lack of self-awareness present in both - the lack of it in AI and the lack of it in the industry's culture of relying on "toxic positivity" in development, as he put it - but his take on AI was particularly acerbic, and in a packed room of very much human animators reaching the finale of a summit that ranged from career advice to desk posture tips, it went down extremely well.

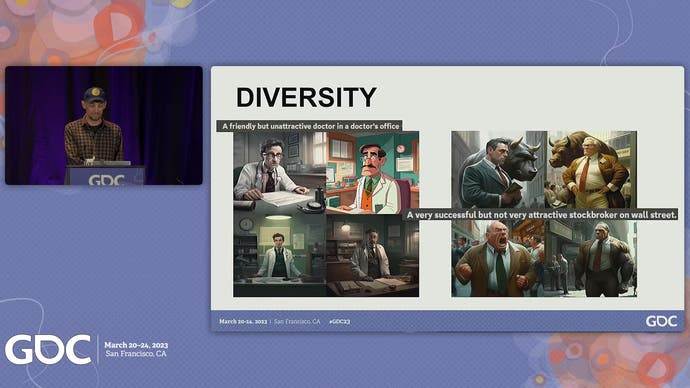

Over the course of 15 minutes he went through a range of AI limitations. "Six months ago," he said, pointing to his screen, "some of these Midjourney prompts might have been paid artist's work. AI advocates freely admit that with potential comes threat, but for gamedev we also need to consider testing, so the machine doesn't fill our games with dicks and Hitler. And the legality of training models is still in question - we can't ship things we can't verify the source of, and AI can be cagey about sources.

"And I don't want to be the woke police here but every human that Midjourney produces is pretty hot; nobody's average, nobody's ugly. Unattractive means not a model, apparently stockbroker means bodybuilder," he continued, as illustrated by a slide with all four results of his Midjourney prompt for "a very successful but not very attractive stockbroker on Wall Street" displaying four comically muscular white men in bursting suits, next to another based on "A friendly but unattractive doctor in a doctor's office" showing four images of a well-presented white man with a moustache and doctor's coat sitting at a desk.

"These are two prompts I fed it, I did not specify 'white' or 'male'. Whatever your thoughts on diversity, that's a blind spot to reality. 'It's just a tool' is pacifying language. You have to remember that not every tool is created with ethics or consequences in mind." Next slide: images of a wheel, an early car, a gun, and a representation of the internet. "Some tools change the course of history, some tools destroy entire industries. It is a tool and I'm not saying it's one of these - only time will tell."

Duffin's ultimate point, beyond some more rhyming one-liners in his song ("It can steal an artist's look, it'll fake an actor's voice; it'll write an author's book and give none of us a choice. They say they democratise, but they've laundered and monetised, and as we starve the tech bros will rejoice.") is that artists are going to have to push each other to "embrace the tools we have, that these computers do not".

"In triple-A, we creators, through our mergers and market research, organised media into formulas and tropes that are predictable and reproducible. Even if AI is just some kind of fancy autocomplete, how many of our interactions or entertainment really challenges our feelings or emotions? Games can be beautiful, fresh and original, but a lot aren't. We're up to our eyeballs in retreads and clones, dosing us up with enough dopamine to not notice. Of course we're at risk of being replaced; we make ourselves replaceable when our entertainment is banal and derivative.

"AI created content is here, and the lowest hanging fruit is junk food. [Am I] saying pretentious artsy-fartsiness is the only way to save our industry? Not everything we want to consume needs to push or provoke us, that's fine, tropes exist for a reason. Sometimes you just want a cheeseburger, and a lot of us are cheeseburger makers - but the robots are gonna figure out cheeseburgers before they figure out duck paté. The advantage we meat sacks still have over the machine is we can imagine, we can critique, and mindfully iterate. AI can produce, but it cannot judge and it cannot feel. Great art can move us, but we can't make things great if we can't talk about them critically."

King's Steve Collins, when asked whether the company's pivot to "AI-first" philosophy might mean a shift from a large number of human beings working on testing, to reliance on their AI tools, said: "I think we still have a large number of human beings, that's the thing! What we're trying to do is: how do we scale? How do we scale or create thousands of new levels?"

"'It's just a tool' is pacifying language. You have to remember that not every tool is created with ethics or consequences in mind." - Ryan Duffin, animation director at Undead Labs.

I asked him how he felt on a personal level about AI and its impact on development, and developers. "I feel two things: I feel incredibly excited by it, that's number one, because obviously things have changed quite substantially in the last couple of weeks, and the last couple of years. And I'd say the other part of it is just really trying to understand how we best take advantage of that and how do we harness it?

"The classic analogy that people talk about, it's a silly analogy but it's sort of useful to use, is when photography came in for the first time - I'm sure you've heard this. Photography came in, everyone thought artists were out of a job, right? That clearly didn't happen - in fact it created a whole new type of artist, a photographic artist. I think we're seeing something similar now, there's always an initial fear of the unknown. The reality is, this sort of technology can be leveraged. What it does is, it can move people up the stack, it can move people to the point where they're being more creative, they have more agency to bring to the content creation pipeline or whatever.

"Midjourney is a nice example. Midjourney 5 just got released last week and it's an amazing iteration. It can produce photographic quality but still needs someone with intent, with a designers eye, to drive that - it also needs skilled people to think about how to harness that technology, and when it produces an image you get four variations and you say 'That's the one,' so there's a direction that happens here. That's design! It's just a different form of design."

Back at Microsoft's talk, when the speakers were gently asked about whether developers, such as the QA testers they'd mentioned, might lose jobs to AI, Kate Rayner responded, "No. It is really a lot of those more mundane and difficult tasks, you know." Zhang responded by emphasising Microsoft's "fundamental belief that AI for games is best innovated with and within the game studios".

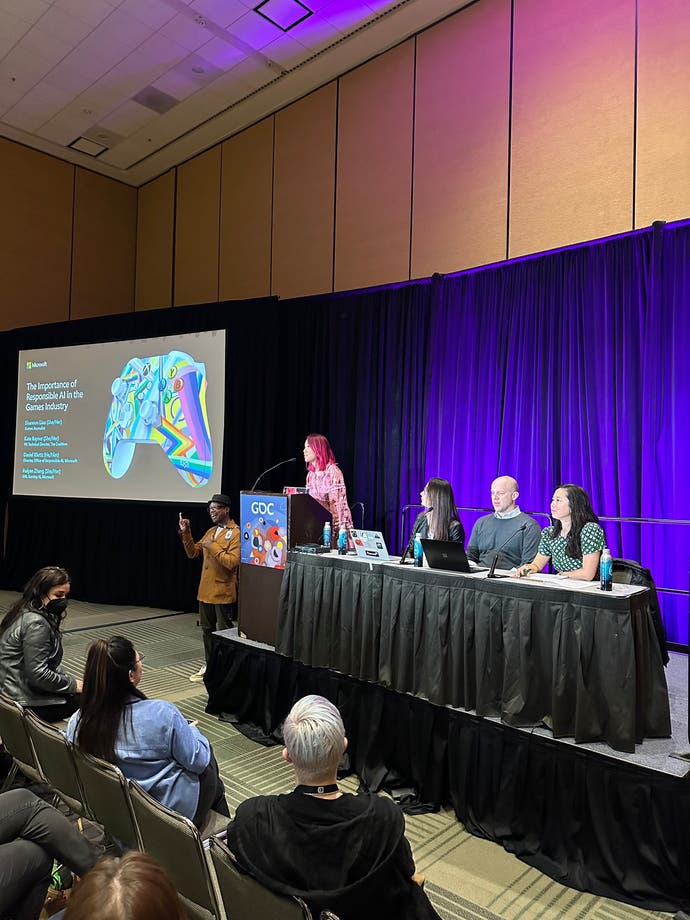

A recurring theme across the more ethical questions, above all, was one of self-governance. Daniel Kluttz, director of sensible uses at Microsoft's Office of Responsible AI, encouraged developers to have a "growth mindset" when it comes to implementing AI, and emphasised how he felt "AI, as a tool, is there to augment and assist, not replace." All three of Microsoft's panellists, meanwhile, repeatedly emphasised the importance of having diversity on staff as a solution to any notion of AI's potential for racial or other bias. For Kluttz, the question of some of generative AI's more controversial points of ethics, like deepfakes, was one he was keen to "reframe" around the individual responsibility of "working with your training data" and again having "diversity" on staff.

King's Steve Collins, when Eurogamer asked about how the company self-regulates and if it has an ethics team at all, said: "Yes we do actually - that's one of the really great benefits of having acquired a company like Peltarion, because as a company, they had an ethics team. Which essentially is: people who are involved in the technology, who really understand it, and are also involved in the business, so working with the businesses, so they served the time, and just making sure they were asking the right questions."

The problem with self-regulation, of course, is there's nothing to stop a company from simply ceasing to regulate itself. Microsoft, for instance, laid off its entire AI ethics and society team in early March, The Verge newsletter The Platformer reported, after apparently promising as late as that morning that its wave of 10,000 job cuts wouldn't affect those team members. When I asked Collins about that, he said, "well we think it's important to have that conversation internally, and we're going to continue to have it! I couldn't possibly comment on Microsoft as company and the choices they've made, but every company involved in this space is thinking deeply about how to take advantage of the technology, but also do it in a way they could make assertions about its impact on users and impact on their business, and society in general, I think every company's doing that." Since this conversation, a Bloomberg report claims Google has also "shed workers" in its AI ethics team, which it originally promised to double in 2021, and has put the AI team on "code red" to speed up its development and make up ground lost to Microsoft by forgoing some of its usual safety checks.

At Microsoft things are rather similar. According to meeting audio obtained by The Platformer, John Montgomery, corporate vice president of AI at Microsoft, said: "the pressure from [CTO] Kevin [Scott] and [CEO] Satya [Nadella] is very, very high to take these most recent OpenAI models and the ones that come after them and move them into customers hands at a very high speed."

The situation with AI in general has also, predictably, continued to move ahead at pace. While developers at GDC debated the hypothetical impact of AI on jobs across the industry, Rest Of World, a global tech publication, reported "widespread anxiety" in China's game art industry, with layoffs already hitting artists reportedly as a direct result of companies pivoting to using AI. One artist, speaking anonymously, told Rest of World: "I wish I could just shoot down these programs," after getting off work late one night, claiming AI's impact was to make her colleagues "more competitive" and stay later at work in order to keep up, the team becoming "more productive but also more exhausted". This played out alongside player backlash against the "digital carcasses," as they reportedly put it on Chinese social media app Weibo, created by AI for skins and posters for games like NetEase's Naraka: Bladepoint and Tencent's Alchemy Stars.

Despite these early warning signs, though - and the sense of both relentless change already hitting the industry and vehement backlash already brewing - the tone at GDC remained more optimistic than not. As Pawel Sasko put it, "I don't think AI can ever be a genius writer, right? I don't think it can ever be like this, because," he said, writing is "much more than just words".

"All of those [AI] are just based on some kind of linguistic models, and the linguistic model is only about predicting the next word - there's no intention behind that. There's no deeper thought or meaning or an arc, you know, of any sort. That is not what it can do. At least right now."

It's already useful for some writing, though. The interviews in this article were partially transcribed using AI, a tool journalists have used for a while. It certainly makes my life easier, taking away one of the more menial parts of writing interview-led features. It's also something that some of my peers used to charge for as a service they provided on the side. And finally, Ryan Duffin's fake title for his GDC talk was in fact written by ChatGPT.

"To anyone who buys or sells the self-aggrandising bullshit of some of these conference talks' names, this is fucking gold."