The History of Nintendo: 1889-1980 review

A book detailing the transformation of the house of cards.

The History of Nintendo: 1889-1980 by Florent Gorges and Isao Yamazaki; Pix'n Love Publishing, £24.99

The first Nintendo shop opened in the Ohashi area of Kyoto on 23rd September 1889, its founder and sole member of staff a gifted craftsman and card-player called Fujisaro Yamauchi. Nintendo is by a distance the oldest company involved in video gaming and over half of its life has been spent making playing cards, most famously the Hanafuda variety, alongside countless variants on a deck. In 1950, Fujisaro's grandson Hiroshi Yamauchi became Nintendo's third managing director and, with misadventures along the way, transformed this sizeable but unambitious card manufacturer into a global titan - a name that for many means no less than video gaming's greatest joys. The History of Nintendo: 1889-1980 doesn't quite explain how this happened, but it does a great job of illustrating the journey.

The History of Nintendo is a recently translated and unofficial production from the French publisher Pix'n Love, and depends throughout on the outstanding Nintendo collection of one Isao Yamazaki, co-credited alongside author Florent Gorges. Yamazaki has copies of almost everything Nintendo has made, in truly impressive condition, and the photography does it justice - though there's sadly a more slapdash approach to presenting things. The History of Nintendo is full of dodgy spacing and busy pages, making it look like a fanzine at times, and many wonderful pictures are reproduced in a miniature form that leaves you squinting.

The overriding flaw in this edition, however, is the extremely poor quality of the translation. There is no glory in picking over its errors and idiomatic oddities, but a fraction of its sentences are meaningless, while most are banal. Consider this paragraph: "Yamauchi had to face the facts and acknowledge the company's protecting God's disfavour for his misbehaviour. After so many failures, many were astonished that Nintendo was still standing. In fact, what helped them carry on was the good old playing cards." You'd hope for a higher standard in future volumes.

There are more issues with the book, but these all have to be considered in context. There simply isn't an equivalent to The History of Nintendo among the slim library of works about the company, so the problems have to be lived with. The early years are detailed in a short narrative introduction that fills in many blanks as well as offering original insights - one of the best being about Nintendo's name.

Often explained as meaning 'leave luck to fate', Gorges instead links 'Nintendo' to the legendary red-nosed character Tengu, synonymous with Hanafuda cards, and comes up with this alternative: "Nintendo could in fact mean 'the temple of free hanafuda' or 'the company that is allowed to make (or sell) Hanafuda'." This only seems more plausible when you know that in 1885, four years before Nintendo was founded, Japan relaxed restrictions on gambling and the manufacture of Hanafuda.

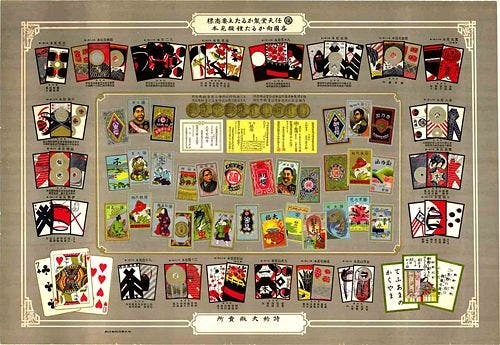

The Hanafuda of Nintendo's early years are reproduced extensively in the book's first chunk alongside some great pictures of the company's premises. From Nintendo's most popular range, the Daitoryo series (best known for the image of Napoleon), this section runs through a boggling selection of cards produced over decades at a brisk pace. Over 30 pages we see Nintendo's house style change from the hand-painted art of its founder into a medley of colourful, mass-produced images - including huge numbers of Disney cards alongside licenses like Popeye and Ultraman. There are also some real rarities here, including a few (tiny!) photos of a Nintendo salesman's Sample Book, apparently the Holy Grail of Nintendo collectors.

Nintendo has always made and still produces playing cards, though now in very limited quantities. A well-known anecdote suggests the point at which it became a sideline, in the mind of Hiroshi Yamauchi at least. In 1956, having been in the job for six years, he visited the US Playing Cards company - the biggest in the world. Expecting something grand, Yamauchi was perturbed to discover that the company's premises were neither bigger nor more efficient than those of Nintendo. As Gorges puts it, "The idea of being prisoner of such a 'small' market until the end of his life appalled him."

From this point Nintendo began to diversify furiously, a strategy that led to some oft-cited failures in the fields of instant rice and 'Love Hotels', and yet ultimately built up to its explosion as a creative force many years later. These sections are where The History really starts to take off, as iconic creations like the Ultra Hand rub shoulders with a bevvy of board games and strange offshoots. Did you know Nintendo made a pram, the Mamaberica?

The momentum towards building products for a younger audience gathered throughout the 1960s. The most surprising thing about Nintendo as a toymaker is that, outside of Gunpei Yokoi's inventions, it had lax standards. Many of its products were derivatives of successful competitors and most were unexceptional staples: tabletop sports games, magic kits, even a doll's house. There's some shameless stuff at the very end of the '60s like the Destiny Game, created after Yamauchi lost out on the rights to the smash hit Game of Life. But even in such company, 1968's N&B is something special.

Standing for 'Nintendo & Block', this was a brass-necked Lego copy that differentiated itself with rounded blocks. Yamauchi smelled the big time with this one, and invested hugely in TV ads directly comparing the two products. Initial success led to a series of over 40 N&B sets, everything from animals to space to fairground rides, but Lego had the trump card - a better product. The N&B blocks were made of inferior plastic and the blocks were often difficult to separate after snapping together. Despite N&B's initial success, and under increasing legal pressure from Lego, Nintendo ended the series in 1972.

The entry on the N&B series in The History of Nintendo is bland, neither capturing the product's arc nor bringing out the details in individual designs. You won't find out here, for example, that Nintendo's brilliant engineer Gunpei Yokoi designed the ingenious springy landmines in the N&B Crater sets. Facts like this - pedantic in any other context - are crucial to a history of Nintendo products. The crazy thing is that I learned this nugget on the website of Isao Yamazaki, the book's collaborator.

This small omission illustrates the main problem with The History of Nintendo. It catalogues Nintendo's history with some thoroughness, largely thanks to Yamazaki's collection, but is unsure how to contextualise and present such a treasure-haul. The products are grouped in chapters with names like 'Toys and Games' and these loose headings give way to a truly chaotic chronology. The constant jumps make it nigh impossible to get a handle on the context of whatever you're reading about, and there's nothing to explain this seemingly random ordering. Neither a catalogue nor quite a narrative history, The History of Nintendo is crying out for a bit of structure.

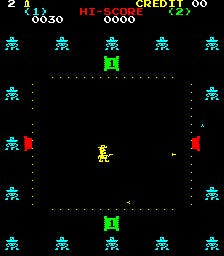

The book's last quarter shows Nintendo making its first steps into gaming. The chapter on its arcade history is one of the best, illustrated throughout with pictures contrasting these chunky behemoths with their rudimentary visuals. Though Nintendo is still making toys at this point - and indeed some of its early arcade machines are basically big toys (check out the Smashmatic) - this is when the company's focus begins to narrow.

Nintendo was not a video game pioneer out of the gate, and its apprenticeship is spent in the shadow of other creators, making variants of Breakout, light-gun games and Space Invaders. The last led to trouble with Taito and an amazing statement from Hiroshi Yamauchi:

"What should prevent us from copying a game's concept if we want to? There's nothing we can do about it! And it is even a very good thing for the sector. [...] Space Invaders probably suffered from this, but this contributes to the entirety of the computer creation sector. Rather than developing games in secret, away from the competition, I think it is very important to communicate with each other and to show other editors our steps in programming development."

Such words remind us that Nintendo was not destined to become Nintendo. It could just as easily have become another small developer or a publisher. That it didn't is down to Gunpei Yokoi's genius for market-creating inventions, a rich seam that runs through the second half of this book, as well as to emerging talents like Miyamoto and Uemara.

The final chapter is on Nintendo's first home consoles, which are less exciting than they sound but nevertheless the baby steps of a giant. These 'Color TV Games' have a single game installed, like Breakout or Pong, with multiple rule sets to make them play differently. The number of rules gives rise to these items' highly misleading titles: the Color TV Game 15, for example, or the Color TV Game Racing 112. This section is great, full of hard facts and some fascinating photography of Nintendo's production lines as well as a few original design sketches.

The History of Nintendo 1889-1980 closes out with a short Game & Watch gallery, which is more of a teaser for the second volume (dedicated entirely to the LCD handheld games). It's an abrupt and rather cursory ending that is followed by an error-riddled index.

The History of Nintendo is not a terrible book, not exactly, because there's no equivalent to it - and it's the first time I've seen many of these items. With all of the above caveats, it's still a must for any serious Nintendo fan. But it is a disappointment. The scale of its endeavour is impressive, but the production is rushed and slapdash. We await the definitive work on Nintendo's history; in the meantime, this will have to do.