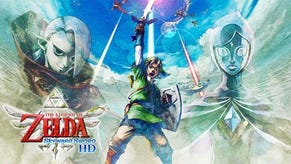

The Legend Of Zelda: Skyward Sword

A decent stab?

Maybe it's because the 25th anniversary concert is only a week away, but the first thing I notice is the music. The swooning classical score is augmented by real orchestration and the effect is as epic and stirring as it proved in Super Mario Galaxy.

For a series light on narrative relative to the scale of its adventures, Nintendo has learned to engage players' emotions by other means: most potently through a shamelessly sweet blend of nostalgia and novelty.

As longterm fans well know, the more things change in Zelda, the more they stay the same. And far from signifying a failure of imagination, the series' consoling familiarity provides a brilliantly successful blueprint that Nintendo endlessly toys with to deliver that "surprise" Miyamoto always cites as his creative goal.

The headline change in Skyward Sword is mechanical. It's Nintendo's first big release - outside of mini-game compendia - built exclusively around MotionPlus, that two-year old Wiimote enhancement largely ignored by game makers.

Turns out it wasn't even supposed to be in the new Zelda game. But it is, and its effects are felt as soon as Link wields his first training sword.

Wave the controller around and Link's right arm (and bad luck, lefties) mirrors your movements with considerable precision.

This precision profoundly impacts combat in the game: no longer simply a case of timing, the direction of your blows matters hugely. Early foes can only be dispatched by slashing around their defences: an enemy shielding to the left must be struck from the right; a plant's vertically-hinged 'jaw' must be swiped along not against; and some only reveal weakspots when flipped over, with an upward swipe.

Link can also unleash a special attack by pointing the sword towards the sky, He-Man-like, which sucks up light energy, while the essential spin attack is performed by flicking both Wiimote and nunchuk to the left.

It requires a level of physical engagement that might annoy the laziest of sofa slouchers, but it makes every encounter feel fresh and exciting.

Traditionally, Zelda games are divided between an overworld and underground dungeons. In Skyward Sword the world is split three ways: the sky, with its floating islands; the surface of the world beneath the clouds; and, of course, the dungeons.

The sky functions like the ocean in Wind Waker, a sprawling map to voyage across, with new lands to discover as you go. Link travels around this realm on the back of his guardian bird, controlled by holding the Wiimote like a dart, swooping, pulling up and tilting from side-to-side.

Link's home - and the starting point for the adventure - is Skyloft, a small island floating above the clouds, packed with a typically eccentric cast of characters and its fair share of mysteries and secrets.

Skyward Sword is not a game in any kind of hurry. Beginning with all the urgency of an afternoon nap, the prologue unfolds gently, neatly familiarising the player with the basics while sweetly exploring the relationship between Link and Zelda.