The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker HD review

New wave.

It is said that the hero of the Legend of Zelda games is called Link because he represents a link between worlds and eras, a link to tradition, a link to all the other various Links who have donned his green garb and picked up his sword and shield. Most importantly, he's a link to you, the player: an empty vessel through which to experience your own high adventure. That's why he has no dialogue, an opaque backstory - he's always an orphan - and few character traits beyond indomitable courage.

Updating the lively sprite of the early games for the 1998 classic Ocarina of Time, Shigeru Miyamoto imagined Link as a stoic enigma and used a time-travel plot to show the boy hero grow into a rangy young man. He had a touch of the western gunslinger about him: the boy with no name, an outsider riding into town on horseback to save the day, then riding off into the sunset.

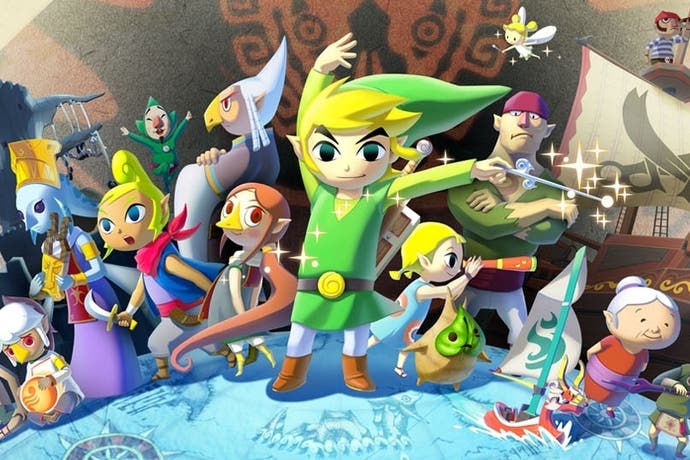

Taking the director's reins from his mentor for 2003's The Wind Waker, Eiji Aonuma had very different ideas. His Link, drawn in a bold, bright, cartoon style, was back to being a preteen in years - but with his huge head and adorable, bandy-legged scamper, he looked more like a toddler. Far from being inscrutable, you could read his expression from a mile off - his huge eyes telegraphing surprise, determination, exhaustion - while the animation conveyed the violent energy with which he attacked his tasks. This time, you wouldn't project yourself into the screen to fill Link's boots; he would reach out and pull you in.

For some who'd grown up with the games, this infantile hero was an unpleasant shock to their self-image. A decade later - playing The Wind Waker in this beautiful new Wii U version - he seems like the best thing about the game, and my favourite of all the Links. He just bursts off the screen. He's impish, irascible and sneaky as well as being courageous - and he misses his grandma. He has a child's magnetism, unfiltered, pure. You still can't quite call him a great character, but he's one of the all-time great avatars. We were all kids once, after all.

The game he stars in also stands up wonderfully. It's a delight: a brisk and manageable game, shorter and lighter on its feet than the last two home console Zeldas, Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword. An efficient prologue wastes no time teaching you a few basics and dispatching Link on a seafaring adventure, first with a motley crew of pirates led by a sassy pint-pot called Tetra, and very soon after aboard his own talking sailboat, the King of Red Lions.

If you know Zelda, you will know what to expect from what follows. There's a town populated with colourful characters with a dozen little threads of domestic drama to stick your nose into, some funny, some curious, some mildly satirical or sad. There's an epic quest for a number of magical doodads, each found in an intricately designed dungeon of traps and puzzles and boss fights where the real treasure is some exciting new tool that can unlock secrets: a boomerang, a mirror shield, a grappling hook. And there are many more diversions besides: mini-games, riddles, mysterious caverns and combat arenas can be found on the small islands dotted across the wide sea, and there's treasure to be salvaged from its depths.

The story is a basic save-the-princess archetype, serving as a simple frame for an adventure that's more schematic than thematic. Yet The Wind Waker does manage a few arresting scenes and memorable characters - and it has a nuanced relationship with the Zelda formula.

This is one of few Zelda games to explicitly acknowledge the events of another; hundreds of years previously, its waterlogged world was the Hyrule of Ocarina of Time. Halfway through the game, the two are tied together in an unforgettable, symbolic scene that enriches everything after it. The game's ebullient tone - far from the elegiac mood of Ocarina - takes on some subtle shading at this point. Even Ganondorf, the red-whiskered villain of many Zelda tales, acquires a motivation, voiced in the concluding scenes, that you can actually relate to. He's sharply drawn here as a more human antagonist, albeit still an evil one.

If there's a problem with the brilliant twist, it's that it's begging for a conclusion that The Wind Waker can't deliver. As polished as it was and is, this game had a rushed development that resulted in substantial cuts - two dungeons were removed, leaving just four, none of them really a classic - and a few fairly obvious bits of recycling and make-do design, including an underwhelming climactic area (although the final fight with Ganondorf is superbly staged). The cracks are very carefully papered over and you could hardly call the game too short, but it can't help feeling truncated, like it's missing something.

On the other hand, the cuts to the big set-pieces give The Wind Waker's remarkable seascape more room to breathe. It was controversial at the time for filling the overworld with so much empty space and long travelling times, constantly interrupted by the need to use the titular conductor's baton to change the direction of the wind. But the sea makes the game feel distinctive and refreshing to revisit now - more freeform, less bound by series tradition than some of the other Zeldas. There's a pure, romantic excitement in the way wind bellies your sail and your little boat carries you over the ocean swell, while the sound of the water rushing against the hull soothes you and clears your head like a draught of sea air. Each of the 49 tiny islands is a thrilling discovery, and filling in your sea chart gives you a particularly rewarding sense of mastery over your surroundings. It's the Zelda game that most makes you feel like an explorer.

Nevertheless, the criticism clearly stung Nintendo, which has added a speed boost for the boat and pruned back one notoriously lengthy fetch quest in this new version (see 'Feel the Triforce', left). Another gameplay tweak is the addition of Hero mode, which can be toggled freely on the save select screen and increases difficulty. Admittedly, in its normal state The Wind Waker is a very easy game. I didn't see the Game Over screen once in a whole playthrough; I can't say that spoiled my enjoyment of the game one bit, although a few trickier puzzles might have been welcome. This would be an ideal first Zelda for youngsters, as well as a relaxing one for their tired parents. And difficult or not, The Wind Waker still offers the most enjoyable combat in the whole series: kinetic, acrobatic swordfighting that's dramatically enhanced by flashing hit-pauses and musical stings, every blow wrung for dynamic impact.

HD 'remasters' are popular these days, but Nintendo has been painstakingly overhauling its back catalogue for 20 years now - all the way back to 1993's superb Super Mario All-Stars collection. No-one better understands how to modify and refresh a game while preserving its spirit, or add fun features without letting technology get in the way. Though a couple of Wind Waker HD's additions are a bit voguish - Link's Picto Box camera can now take selfies, and you can send messages and photos into other players' games in Tingle Bottles that wash up on their shores - this is a typically sensitive and handsome revision.

The Wind Waker is a profoundly beautiful game. Its 'toon-shaded' visuals use flat planes of colour, stylised effects, stark lighting and hugely expressive animation to bring a cartoon world to life all around you. The original has aged so well that some have questioned why Nintendo has gone as far as it has in reworking it for HD. It's true that the softer lighting makes the characters look more three-dimensional at times, breaking the toon illusion, but there are ample compensations. Improved lighting and effects grant the game a far richer atmosphere: the sea air shimmers with haze; you can taste the dust in the Temple of Earth on your tongue. Every line is sharp and the creamy brushwork of the textures is rendered in total clarity.

I think it's gorgeous, and in real terms it looks far better on a modern widescreen TV than the original game does. But unlike Capcom's remaster of Okami, it does represent a subtle yet identifiable change in the game's aesthetic, so purists and collectors of video game art - of which The Wind Waker is such an important and influential example - shouldn't throw away their GameCube discs.

Out in the real world, though, video games are cursed with technical obsolescence, and a game like The Wind Waker - which in any other medium would be an evergreen family entertainment - quickly becomes difficult to find and play. That's even more of a shame when it's such a daring game, made under such pressure and released into the long shadow of a very different predecessor. By the time critics and gamers had stopped arguing and started celebrating it, it was already fading into nostalgic memory, a dream adrift on the waves.

That's not a fitting fate for this Zelda and certainly not for this Link, with all his vivid urgency. It's why we need excellent re-releases like this. Just like its young hero, The Wind Waker is crisp and energetic, spirited and soulful, just a little bit wayward - and it hasn't aged a day.