The making of Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior

Full metal bikini.

It's some time in the spring of 1988. Steve Brown, creator of the smash hit games Cauldron, Cauldron 2 and Barbarian, is holding a pair of pliers while in the midst of a dramatic photo shoot for Barbarian 2. "Maria would breathe in heavily and the pressure from her bosom would snap the thin chain joining the metal breast plates together," smiles the former Palace Software artist and designer. "I spent a fair amount of that day with those pliers, bending all the links back together." They were different times.

Palace Software had begun life several years earlier as an offshoot of The Video Palace, a popular video store on Kensington High Street, managed by Peter Stone, and owned by the Palace Group. Working as a sales assistant was Richard Leinfeller, and when the shop began selling video games, in store and by mail order, the pair saw something special happening. "Kids, young adults were coming into the store with cassettes full of games they'd written," recalls Stone. "So as things went on, Richard and I thought we could maybe publish some of them ourselves, or even make our own games to publish."

With the new venture given the green light by Palace chief Nik Powell, the subject for Palace Software's first game was inevitably a licence owned by its parent company. "We made a game of the Evil Dead," winces Stone, recalling his and Leinfeller's first effort in the videogame market. "And it was a bit rubbish. But it showed us how not to do things." Despite Richard Leinfeller's coding experience, the pair realised they needed help, especially on the art side. The call was answered by Steve Brown, at that point inexperienced but recently qualified, and eager to tackle the new role. "Steve had never done a video game before," recalls Leinfeller. "One night down the pub he asked why there were platform games and scrolling games. I told him there was no reason why we couldn't mix the two, and Cauldron was conceived."

Cauldron and Cauldron 2 were massive hits and helped establish the new software house. "I studied illustration at Richmond college," explains Brown, "and just by chance came across an advert in Creative Review for an artist at Palace. They hired me to create some sprites for the Evil Dead and the cover art to a couple of simple games they had made." After the decision to go with the genre-mash up as suggested by Leinfeller, Brown became a freelance designer in addition to artist, and pitched a pumpkin-based game to Peter Stone. With the success of the Cauldron series ensuring reputations were established all round, Palace looked for new ideas from their creative director. "Steve was very soon into his stride, and after Cauldron 2, he didn't even need to pitch to me," recalls Stone. "He was working on different ideas all the time, although it was still a team effort." One idea that Brown settled on was heavily influenced by his love of that most famous of barbarians. "My artistic hero was Frank Frazetta," he explains, "who painted these incredible images of sword-wielding barbarians, leaping about, hacking up monsters while saving sultry maids from a fate worse than death. And Conan The Destroyer was the king of these muscled heroes." The plot devised by Brown was stereotypical fantasy fare, not that the game needed more. An evil sorcerer named Drax desires the exquisite princess Mariana for himself and will only free her from his nefarious clutches should a champion be able to defeat in combat all of his demonic minions. Guess what? That was where YOU came in.

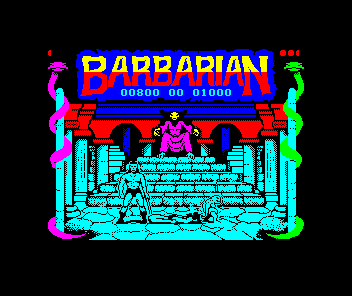

Even by 1986, an elderly, if famous, one-on-one beat-'em-up was dominating the genre. "Way Of The Exploding Fist was probably the key influence," says Brown. "It was a fun game which had decent character animation, still rare at that time. But to be honest, my influences always came from other sources, and in Barbarian's case I was extrapolating the fun stuff from the second Conan movie."

Conan The Destroyer, produced by the Dino De Laurentiis Company in 1984, informed one particularly crowd-pleasing element of Barbarian. "The best example of fighting with large barbarian-style swords was, for my money, in that film," explains Brown. "So I took what I considered to be the best attacking and defensive moves from the various fights in the movie and devised a logical system of how to incorporate them into the game."

The most memorable of these was a satisfying decapitation finish move that pre-dated Mortal Kombat by several years. "Most of my ideas come from asking myself the question: 'what can I come up with that would be really fun, a bit outrageous, and no-one has done before?'. If you can hit all three of those, you're on to a winner." The icing on the cake was a poor downtrodden goblin, whose job it was to remove the remains, kicking the stray bonce off-screen, complete with a maniacal cackle. "I hate loose ends and sloppy design, so wasn't keen on having the head just wink out," grins Brown. "The goblin appealed to my sense of humour, and the idea came to me on the train journey home after a beer with the other guys. Actually, I think I get all my best ideas on train journeys!"

Leinfeller himself was still involved in development at this point, assisting Palace's trainee coder Stan Schembri, and helping to write a bespoke sprite multiplexer to aid the animation of the rotoscoped sprites. "The game needed big sprites. That was a lot of work, and needed critical timing," explains Leinfeller, "and was very fiddly as both it and the audio ran on interrupts." However, the development of Barbarian ran smoothly, as Stone notes. "The three main leads, Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum and Amstrad were developed more-or-less simultaneously, yet I think it was the fastest game we made. No problems at all."

But of course, mention Barbarian to most players of the era will bring back not only memories of goblins and detached heads, but also an advertising campaign that generated a considerable amount of controversy, and sales, for Palace.

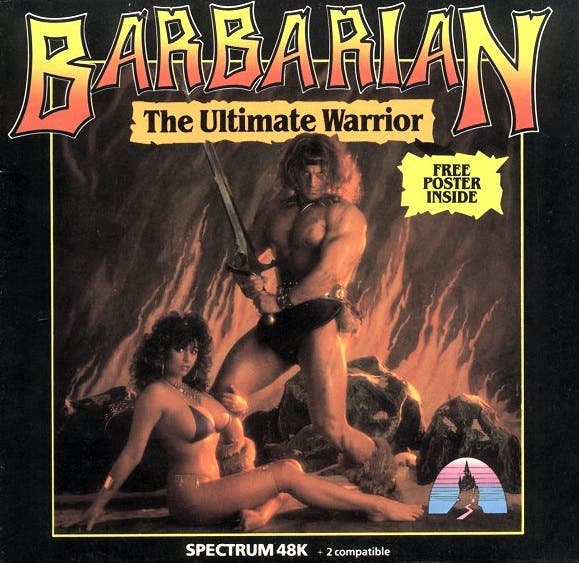

Most video game box art and adverts at this point in time were still hand-drawn, usually by very talented artists such as Bob Wakelin. Brown's cinematic influences led him to explore a different path. "I had it all visualised in my head," he reveals, "and knew it would look great if done properly, and generate some good publicity. Plus, being creative director on that kind of shoot was another of my ambitions - so it was win-win for me." Two models were required for the campaign: someone to play the butch, over-muscled hero, and another for the beautiful princess.

For the former, Palace secured the services of pre-Wolf bodybuilder Michael Van Wyk. "I then owned a gym in South East London," Van Wyk told me via email from his current home country of New Zealand. "And one of my members told me that I had the exact look that they were looking for in a poster for a new videogame. I must confess I have never been into games." Van Wyk took the job, not that it interrupted his busy schedule much. "I was training five days a week, so didn't have time to prepare. Anyway, I was just asked to turn up, and that all the costumes would be provided. I was already doing some TV and photo shoots and [Palace] were very professional in their handling of everything."

The second role, that of princess Mariana, was played by famous page three model Maria Whittaker. "Maria was initially a bit hesitant when I showed her the Frazetta painting of the Egyptian princess with a snake wrapped around her," grins Brown, "but I put her mind to rest to the extent that by Barbarian 2 she was happy for me to mould foil ashtrays to the shape of her breasts, which I then took back to my shed and used as a template for the finished fibreglass breast plates in the advert." For the original game, the model merely sported a purple bikini, more than she would usually wear for her newspaper appearances. "She was very nice to work with, very professional," Van Wyk told me, "and a very sweet lady, too."

Surprisingly, considering Whittaker's fame, her services were not prohibitively expensive, as Peter Stone recalls. "We contacted her agent, and the funny thing was, it wasn't that pricey. We discovered that, despite her fame, she had a set rate for doing different types of work. Her rate for a photo session was actually quite affordable. However, personal public appearances was a different story. I remember we wanted to do a launch event, but her price for that was way way more than for the photo shoot, so we couldn't get her for that." The moral outrage of featuring a page three model on the cover of a computer game (games were still firmly considered for kids in the mid-80s) wasn't the only controversy for Barbarian - its violence also incited a predictable furore. "To be honest, I've always created the games that I've wanted to play," notes Brown, "and luckily my taste was appealing to a lot of people. I used to receive a lot of hand-written fan mail for the games, many with drawings of the characters, usually much more bloodthirsty than anything I'd presented them with!" West Germany, as sensitive to the influence of videogames as ever, banned the game until Palace changed the blood to green and removed Whittaker from the cover. "I found it all incredibly amusing, to be honest," notes Brown, "and quite hypocritical, as it was all appropriate and in context - pretty much the opposite of page three of The Sun."

Barbarian and Barbarian 2, along with the Cauldron series, became the games that defined Palace Software as it struggled into the late-Eighties, post 8-bit era. With its parent company, The Palace Group, now involved in the money-pit of film production, the software division was sold to French publisher Titus in 1991. Steve Brown was working on a second sequel to the series as the sale went through. "It was a great shame as I had Barbarian 3 mostly planned out, including the publicity, which was going to feature my other favourite model of the time, Debee Ashby. I'd designed and had miniatures built of a giant tentacled monster, plus had a meeting with the monster makers at Pinewood Studios about constructing a full-sized animatronic tentacle that would lift Debee up in the photoshoot. It would have been awesome!"

Despite the abrupt ending for Palace, its place in videogame history had been assured by the violent and bloody-good-fun of Barbarian. "It put us on the map as a publisher," recalls Peter Stone, "and kept us going for quite a few years. But it was the peak of our success and we could never match it." Sadly, three of the team involved, Chris Stangroom, Stan Schembri and Richard Joseph are no longer with us. But the memories of them, and the great times on Barbarian remain for all involved. "It was long hours, stress and weekend working," says Brown. "But it was also the best time ever, and completely faithful to my vision. Most of all, I'm incredibly proud of it as a game, and that people are still talking about it 30 years later."