The Making of God of War III

For the love of God.

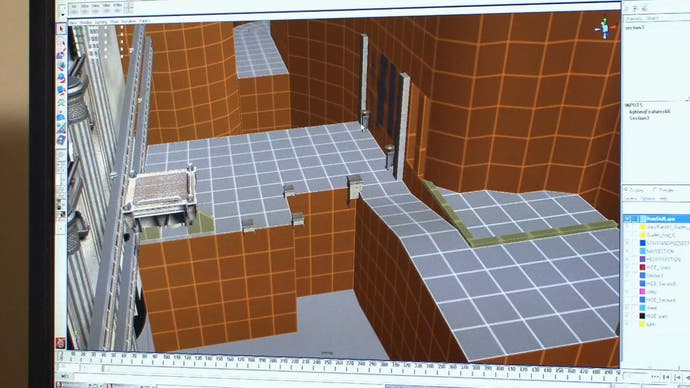

Sony Santa Monica actually has four team members looking after this, while a good proportion of one of the programmers' time and effort is also spent making this all-important element of the package looking right.

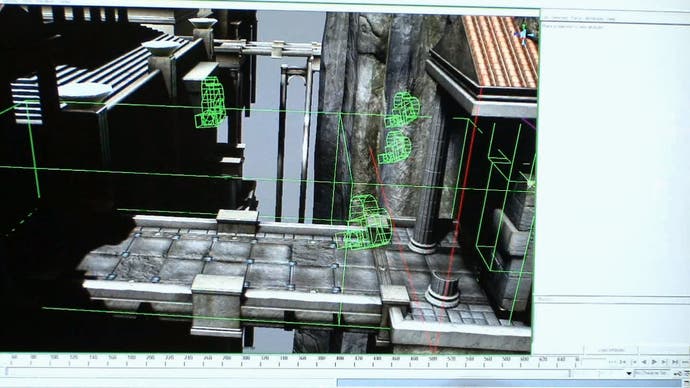

"Cameras start by the design sheet being delivered to us by the level designer - that's the most basic form," says camera designer Stephen Peterson. "We put in all the cameras for the design sheet. Once the cameras are in and it's been playtested and it's been proven to be a good concept, we go forward with it and it gets sent off to the art department."

"That's where they'll spend months - sometimes - making these areas look really epic," adds lead camera designer Mark Simon. "They'll hand it back to us and lot of the time it'll be a little bit different and we'll need to adjust some cameras."

"Once the art has come back in and someone has spent a year building that level they can be very touchy if they spend a year styling this formation and my camera goes right past it," explains Stephen Peterson. "We try to do our best to show off everyone's hard work."

While striving for a cinematic feel that showcases the best of the designers' efforts, the cameras themselves also serve as guides to the player. The basic viewpoint in just about any traversal scene acts like a shepherd of sorts, pushing you in the right general direction. While players might crave an Uncharted-style free camera mapped to the second analogue stick, that's not the way Sony Santa Monica rolls. Its pursuit of the cinematic experience is tied closely to having control of the player's perspective on the action, and the game world.

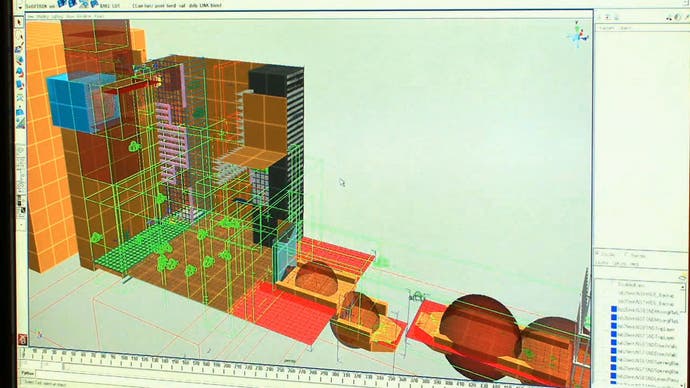

While strict camera controls may have a bearing on "budgeting" a scene from a technological standpoint, God of War III doesn't apply in this regard as the viewpoint is dynamic, adapting to the gameplay and constantly striving to give the player the most satisfying outlook of the action.

"The camera is not fixed. It is highly scripted to provide a highly cinematic play experience, yes, but in no meaning of the word is the camera fixed," director of technology Christer Ericson explained on the Beyond 3D forum.

"Within the setup cinematic parameters there is a lot of room for the camera to adjust to the action that happens on the screen (where the player is, where the enemies are, etc). Because of the amount of adjustments the camera system can make automatically, there are very few assumptions that can be made about what to render or not render...

"We could easily allow the user full control of the camera during gameplay. The reason we do not is because we feel it breaks the cinematic experience that we have carefully crafted, not because there is some geometry missing if you turn around..."

Ericson likens the implementation to the dolly used in film-making, with the camera on an arm, able to move in, out, pan, zoom and tilt.

"Which of these movements the camera makes is dependent on parameters that our camera designers have carefully set, but ultimately on the location of the player and the enemies on screen," he says. "This decision is made at run-time, not tool-time... for every game frame, we determine at run-time the position and orientation of the camera. In other words, the possible movement space for the camera is an irregularly-shaped 3D volume, not some simplistic 'glide path'. As a general rule, neither position nor orientation of the camera within this volume can be predetermined for any particular gameplay moment."

The relationship between the camera guys and the other departments in the team mean that while you might think a scripted camera to be "easier" for the developers to deal with, the logistics of maintaining that all-important cinematic experience are probably just as hard - maybe even harder - than simply handing over control to the player.

"Every level requires a camera design stage that has potential cross-dependencies with every other department, well, other than concept art. That alone tips the scheduling and budgetary considerations seriously against us. This is not an easy road," says Sony Santa Monica's Phil Wilkins.

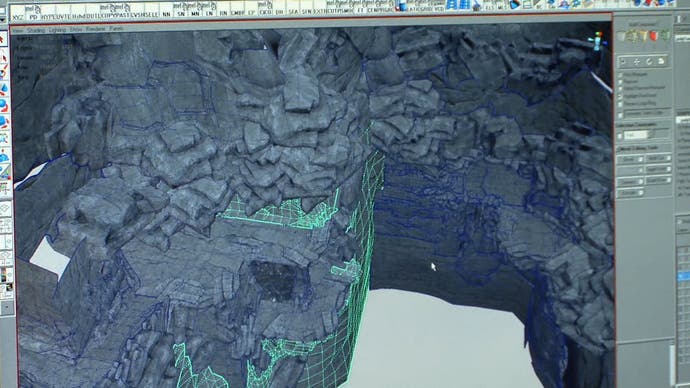

"The only performance benefits are that we can focus asset creation quality on what we want to look at. Sometimes this means that we don't need to build the back wall of a room. Or we can unload an area behind us that we can no longer see. Although often we'll just swap it for a lower-detail version of the same area (think of the horse/chain section of God of War II).That's entirely in the domain of the artists and designers though."

Camera is a crucial element to God of War, and the fact that the player isn't in control means that for some of the puzzling stages, it's important for the scripts to include an overall view of the surrounding area. In this case, an on-rails camera provides the goods, and is also used to good effect to get the best possible viewpoints on some of the game's most spectacular levels. The game sets out its stall in an enormously effective manner in the very first level, which pits Kratos up against the god of the oceans, Poseidon, while circumnavigating Gaia - a titanic figure as tall as the Sears Tower, over 1400 feet high.

As you can see from the video, this initial stage from God of War III showcases many of the technological improvements the team made for the sequel. Not only do you see a range of dynamic, on-rails and combat cameras, but you also see that Sony Santa Monica has taken a stab at its own rendition of Naughty Dog's dynamic object traversal system - the whole level can be animated and moving, and the action on those moving surfaces is affected accordingly.

"There was no way to do this level of scale on the PS2 - just not enough memory," says Ken Feldman. "Most games are centred around a room-to-hallway design because engines do that really well. It's really easy to put tons of detail in small rooms but it's a whole different challenge to create a massive spectacle - and that's the challenge we undertook."

RAM management must surely be immensely challenging here. Textures and geometry need to look sufficiently detailed at both the micro and macro levels, and to enable seamless transitions between the two, both would need to be kept in the system memory. To illustrate, Kratos may well be nothing more than a small speck in some of the shots, but that memory-intensive 20,000 polygon model is still in RAM.