The making of The Making of Karateka

"If you ask Neil Druckmann what inspired him... you're going to get back to Karateka."

At the end of October, Digital Eclipse, the team behind the wonderful documentary game, The Making of Karateka - and the gorgeous Atari 50 collection - announced it was being acquired by Atari. Just before that happened, we had a chat with Chris Kohler, Digital Eclipse’s editorial director, and Mike Mika, the company’s president, about the studio’s work keeping game history alive in dynamic, playable form.

Following acquisition, the studio will keep working on games like The Making of Karateka as part of its Gold Master Series. If you’re interested in hearing a little about the process of making these playable slices of history, I hope you enjoy our chat.

(Mike Mika arrived a little late so he pops up towards the end of the interview.)

Eurogamer: So I wanted to talk to you about the emergence of what feels like a slightly new documentary form. But before that, I just want to say that when I played The Making of Karateka, I was really moved by it. And I think part of it, with the recent game, is this wonderful story between the father and son that emerges. I think also it's just the sheer impact of games being treated in such a delicate and thoughtful way. And I wondered, is that a common reaction to these things you're making?

Chris Kohler: Obviously we're gratified whenever we get that reaction, because that's precisely what we're going for. We've done so many, over the course of the history of Digital Eclipse - the sort of standard retro collections - and for all of them, we've always been trying to push the boundaries of what we can do. How can we get more of the history in there? Not just because we're history nuts - we are - but because we really believe that to do a great service to these games would be to not simply take the game and say here, go play it, but to take the player on this journey.

Retro collections give you the "what?" - here's the game - but we want to do the "when?" and the "who?" and the "how?". And, importantly, the "why?". If you understand not only how the game was made and who made it, but what the context was around it when it was made and, importantly, why this game was made. When you have that and then you play it, you have so much more appreciation - if we do our job right you should have so much more appreciation - for what it is that you're playing.

That's really important because if all we're doing is just releasing the game over and over and over again, and that is laudable to keep that game in print - we know from the Video Game History Foundation that of the games released prior to 2010, only thirteen percent of them are even available right now, and eighty-seven percent of everything is not commercially available. So it's good to have it commercially available but you're not growing the audience. You're not making new fans of it and you're not understanding where that game came in history.

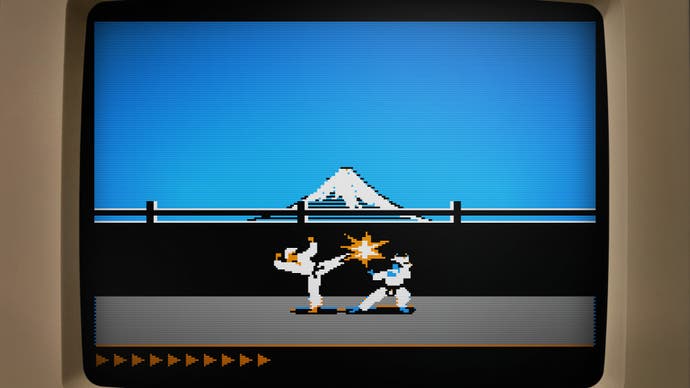

With Karateka, it's like this game very specifically inspired a generation of designers that came after it. Karateka did, not games like it - that game. And when you play The Last of Us, you can trace the line back. If you ask Neil Druckmann what inspired him and you keep going back and back and back, you're going to get back to Karateka. But the thing is, people don't know that necessarily because a lot of that game has been forgotten. If you just play it, you're like, 'Oh, this is a video game.' But if you understand first that it was the first game for people that felt like a little movie, that had all these cinematic elements, that told the story - if you understand that, you have so much more appreciation for it.

Ultimately, it's all about learning about history and preserving that history, and getting this game its place in history. And also so we can understand the full story of who made it. Because we think about Jordan Mechner but we really need to be thinking about Francis Mechner, his father. We need to be thinking about Gene Portwood and Lauren Elliott at Broderbund. You need to think about all the people that have this impact on it.

But then additionally, you're also supposed to be having fun - it's a video game, silly, you're supposed to be enjoying yourself! It's not supposed to be school. So we have to ask the question of how do we keep the player engaged learning all this? We could take this all and write it out in thousands of words and make you scroll through texts, but that doesn't make sense either. So it's like, how do you break that up? How do you gamify it? A lot of it, we're going off vibes, because nobody's really done this before. It's like, "We think this is right..."

So to bring it back to that level of feedback, that people are going away from the Making of Karateka with not just, "Oh that's a good way of showing the history of a video game". When people say they emotionally connected with that story, that they're like, "I didn't expect..." Somebody said they cried, you know what I mean? When somebody's that engaged it's like, okay we've got lightning in a bottle here - we're doing what we're supposed to be doing.

So one thing you said is often with these classics, you think you know the story of them. And I wonder if, for you in your position working on your side of this, when you put the story down and you have all these pieces and you're pulling them all together, are you ever surprised by what the story actually is? Because I've read lots about Jordan Mechner, and I've read lots about his dad doing the sound and stuff like that, but I'd never realised, until you see the way that relationship unfolds, about the delicacy between the two of them. It's incredibly moving the way they speak to each other. The respect that flows both ways I think is just so beautiful. Are you ever, when you put these things together, like, "Oh!" Do you make discoveries along the way?

Chris Kohler: Yes absolutely. You have to go in with an open mind, right, especially in video game history, because there's so many very pat, very simple stories that we've all been told about it. And you have to be ready when you start doing this research to have those assumptions flipped on their heads, because so many of these stories are not what we were told.

It's like when we did Atari 50: The Anniversary Celebration, and going back and re-evaluating the Atari Jaguar. Because the Atari Jaguar, what a lot of people know about it is as a punchline. It's like, "Oh, this is a bad video game system." And really it wasn't a bad video game system. It was a commercial failure, but a lot of people designed original games for it that are actually very playable and fun, and interesting. But the problem is, since the Jaguar wasn't even emulated properly before Atari 50 came along, you would have no way of knowing that without going out and purchasing the system, buying all these extremely expensive games.

It's a blessing in my job - during my literal nine-to-five day job - to be able to explore all of these things with all of that time. I also spent twenty-five years as a journalist. It's like, as you know, real-life is very messy and you have all these little pieces of stories and you have to start seeing where is the through line? What is the story that's being told here? And you have to have that editorial eye for it. Especially with the Making of Karateka, you have to start figuring out - as you're putting this stuff together - where's the drama? What are the stakes? Where does our hero start to fail, and by what process does he figure it out and bring it back? There is a very traditional three-act story being told throughout the Making of Karateka, and that's because we're looking for that - we're trying to find what that is. You can't force it but it's there if you look for it, and that's what's going to engage people, because they've got to be. It can't simply be "this happened and this happened and this happened, and now it's over". There's got to be that through line.

One thing I also thought, particularly with Atari 50, is you're responding to what was, even in the very early days, an art form like no other. A friend of mine said, "The thing about video games is that other art forms, like music, visual arts, editing - these are all sub-problems of games." They contain all of these, and then they contain agency and scores and all of these other things as well.

What I love about the recent game is you load it up and you think you're getting told this story, and then the game - for me, I had almost this image of a paper castle just exploding out of this box in every direction. I was like, "Oh my god, this is huge!" There's stuff in every direction. I guess what I'm saying is, does doing all this history work with games make it more challenging, because games are these incredible kinds of nth dimensional objects which have so many compartments to them?

Chris Kohler: It is challenging, but it's a different kind of challenge, because the challenge that is answered is: if you were to try to do this in a film, then the film has to be aggressively linear, so you start here and you end there, and you can't take it at your own pace, you have to sit there and watch it, so you have to think about the viewers' experience in that sense. But with a video game, we don't actually have to do aggressive edits to figure out what's in and what's out. Everything can be in, and everything can be in because you, the player, have that control. And if you look at the way things are organised - you have the horizontal timeline - if all you want to do is just zip across that main timeline, you can do that, you can get the whole story. But then if you want to drill down into the vertical sections, you can learn more - and even within those vertical sections, there can be a photo gallery of like fifty design documents. You can't show all that in a film. You could do all that in a book, but it would be a very thick book. But in this case, we show you the gallery, we give you a sense of what that is. Then it's like, well do you want to dig any further? And ultimately it's up to you as to whether or not you want to do that.

So you have this pop-up book sort of experience that might not necessarily be somebody else's experience, and that's okay. But then you also see, if they're looking at the Apple 2 Karateka game - we have the commentary track from Jordan and Francis in which they start talking about various things that went into the design of the game. So the idea is, no matter where you go, we're trying to hit you with something that enlightens and illuminates your experience. But then maybe that causes you to go back and to look at the stuff that you weren't going to look at before.

That's that's why we believe the medium of the video game is the absolute best way to tell the story of a video game, because it gives us the ability to bring in all of these things. We have a fifteen-minute audio podcast in there. We can just do that. This is also why it's important that we're doing this independently, because we don't have to go make the case to a publisher that they should allow us to do this. We just do exactly what we feel is okay.

It's very important when you're a player [that] if you have a controller in your hand, you feel like you need to be in control. We can point you to things, we can guide you to things, we can set up a linear experience, but ultimately if you have that controller, you're going to feel too constricted and you're not going to like your experience.

So I'm leaving my questions behind now and just following instinct, so apologies! Two of the things I really loved about the recent game are the demo of Earth, the prototype, which is just the 8-bit planet and a little thing going around the outside of it. And then also the pocket watch - I think the pocket watch without a face in it. I read a book recently by a pilot - there's a British Airways pilot who writes wonderful books, and he wrote one called Imagine a City - and it's full of facts. And he has this thing at the back, in the acknowledgments, where he's talking to his editor and his editor would say, "This is one fact too far - you're giving us one fact too far now. It's a bit too much." Do you get to these points? I know you said you can do anything (and you do have a fifteen minute podcast in there), but also when I play this game, it feels perfectly suited to attention spans - it feels like you've thought a lot about how long people can follow one path.

With capturing these funny little things which actually might be really important to someone, like the prototype of Earth or the pocket watch without a face, is there a trade-off? Do you have a lot of soul searching about, is this a fact too far, am I going too far off the track? Because with someone like Jordan Mechner, I imagine everything he does is interesting, so where do you draw those lines?

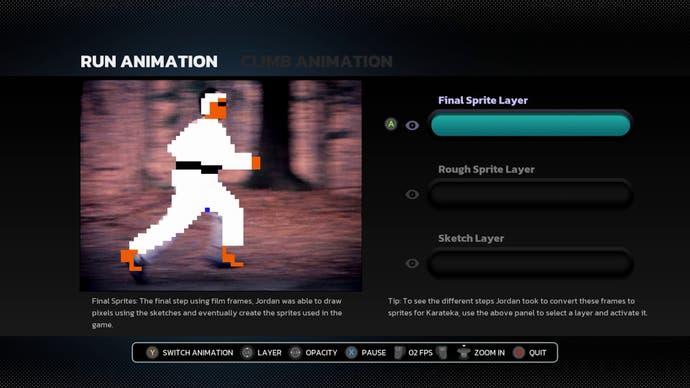

Chris Kohler: Well we could have put in anything we wanted from Jordan's journals, but that would have been a lot of reading. You mentioned the pocket watch: that's an indication that you can't just look at one thing, you have to look at everything, because if you found that pocket watch on one of Jordan's floppy disks, you might have looked at that and said "not sure what this is" and moved on. But I encountered that after I had read through all of Jordan's journals and made a whole lot of notes about some things he'd cut out of a game, so when that screenshot came up that showed the digital clock on it, it's like "I know exactly what this is". I know the day that he worked on it, so I knew that was actually very important to the story that we were telling. But Jordan's journal: there's tons of stuff in there, so we want to try to make very judicious use of that.

One of the things that I felt was really important was when those journals get emotional, when he starts swearing, because it really humanises what's going on there. You actually see some of the more emotional, exclamation point, curse-filled entries because you have to add that emotion somewhere. There are a lot of basic details and things like that that are left to the journals. If you enjoy playing this game, just go back and read the journal now and get all the rest of that information.

This game has such an incredibly clever structure, and one of the clever things about it is it feels so natural. You're going through in chapters and like you said, you're going along and then you go down. So one of my favourite things Digital Eclipse ever made was Midway Arcade Treasures, because I love Eugene Jarvis particularly, and I remember being so excited that there were clips of him in it. This was 2003, I was a big Eugene Jarvis fan, and I was fascinated there were clips of him actually speaking and how dynamic he is. You've got this incredibly elegant structure and I wonder how long did it take you to arrive at it? Because it feels like you're inventing a new form, like Errol Morris does documentaries his way and you guys are doing documentaries your way, in a video game, and it feels like it had to be something new. What was the process of getting to that like? Were there a lot of missteps or did it come together quite naturally?

Chris Kohler: Well the nature of the material that we had for Karateka itself was very helpful. I came into the company in 2020, while there was an earlier version of Making of Karateka, that had been worked on by some people that had left and some people that were still here. And it was a little bit more of a sort of a museum-type thing, where things were sorted - when you were going through the artefacts - by category. But with Jordan's journals being available, it really seemed like the best way to sort these would be by time and then to bring everything together. So we started working on this timeline concept where everything was chronological, essentially. We had done a rough version of that. And as we're doing that, some things start to emerge. There's a lot of stuff on this timeline and it takes a really long time to go through it, and we were still working on getting games playable off of that timeline. So as we're doing that work, some deficiencies start to appear.

At that point, before we could really get in and start going too crazy on it, we signed the contract for Atari 50: The Anniversary Celebration, and that was an all hands on deck thing because that had to be done for the Atari Anniversary here or it did not make any sense. This, then, took everybody; Karateka had to be put on the shelf.

Then, knowing a lot of that when we sat down and started designing what would be Atari 50, that's when we started doing, okay you can move downwards, you can do some that way. Should we have galleries? Yeah, yeah - we can do galleries. What we were able to do is take a lot of these ideas that we were working on, that were in pretty good form, but take it all the way to the finish line. A lot of that we were able to then bring back into the Gold Master Series - a lot of those learnings - and then we could add even more on top of that.

But yeah, we definitely realised this was an organisational and design problem. But a lot of those organisational and design challenges came from the fact that there was just so much - with the Making of Karateka - from Jordan's journal entries that we were going to have to figure out a way to do that that made sense for the viewer.

So one of the things when I was watching it, and playing it, I felt it was very novelistic, because I felt what was coming through was a sense of his character, and by the end of it, I felt like I understood him much better than I had at the beginning.

But what I'm interested in is - and this is going to sound like I'm leading you to tell me whether you're doing one on Eugene Jarvis, and I promise that's not the case - I can't imagine someone who's more different from Jordan Mechner than Jarvis. I've interviewed him before and he has that look in his eyes like it's always Halloween - he's quite an anarchic kind of character. And when you're dealing with a different kind of person, telling a different museum history story about a different creator, do you think the structure has to reflect that in some way?

Do you think that the structure you're doing here is going to change, topic to topic - not just in terms of how much they have kept - but just in terms of expressing the nature of the people involved? This approach seems to suit Jordan so well - he seems to speak through everything in it, like the clarity of the menus and everything. Hi Mike! [Mike Mika joins the call at this point.] Do you think when you have a different narrator or a different protagonist, the actual structure is going to have to change a bit to create that sense of who they are?

Chris Kohler: At this time, I don't think we're looking at totally reinventing the wheel when we've got this structure for these timelines and it seems to work really well, and you can slot whatever you want into it. Obviously Karateka, there's no other game like it that we would be able to do something like that for, that wasn't made by Jordan, but otherwise, the structure itself is a template that we can apply things to.

It starts with the research - we don't start building it until somebody has really done the research and is able to go in and say "we need this for this person because...", so you will certainly see changes that are made based on what kind of story are we going to tell, what sort of games did this person make? Or, what kind of games did this company make, or what platforms do we need to address, or is there anything we need to do as a layer on top of those games? So we'll do that incrementally. But I don't think there's going to be any sort of mass reshuffling any time soon.

Can I ask you both now that Mike is here - and thank you both, by the way, when I played Karateka I just needed to speak to you, to hear about it. It was a very rich experience for me. So one of the questions I wanted to ask, and this is a hard question for you to answer - it's one of those ridiculous questions people like to ask - this product you've made is all about putting this one game in context, the widest possible, most enlightening context. But do you look at what you're doing now, what Digital Eclipse is doing with this, and see yourself in the context of something?

I mean, obviously Criterion and its lovely editions come to mind. But are there other people you think, and it may be even in a completely different medium, that you're doing the sort of things that we're doing - you're going out and getting these unusual stories and you're finding the most interesting, harmonious way of telling your story? That's what it feels like to me. Do you see anyone else who's doing things, even if it's very different to you, where you're like, that's cool and I can kind of imagine that we have some shared experiences?

Chris Kohler: One of the things I think is wonderful, and I really hope it's a huge success, is Limited Run Games, particularly with Plumbers Don't Wear Ties, because that is something we've talked about internally - not that game in particular but the idea that you could take a game that was one of the worst reviewed games of all time, and you could turn that into a product that people will be excited to go and buy and engage with, because you are decentring the game itself, and you are centring the story behind it. That game has got to have a fascinating story. And I know that's exactly what they're doing - they're doing the full kind of Making Of, behind the scenes, and that's essentially what they're selling it as. I really want to see that do well because it expands what we could potentially do as well, because yeah, we could bring back a really terrible game also. But then people would be like, "Oh, I want to buy this," you know? So it just totally changes the calculus of what is a viable game to get back into print, and what are the stories? We don't just want to tell the stories of the winners - that's not history. So what are the stories that we could potentially tell?

Mike Mika: The work that M2 has been doing over the years, where they'll take a game and they'll expose the mechanics of that game, and display those in a way that you understand the inner workings of a game visually, for Phantasy Star and that kind of stuff - that stuff has always blown my mind. They were ahead of the curve on all this stuff. And when we're looking at telling a narrative, that narrative isn't just images, it's not just somebody talking to a camera, it's the sum of all those parts. So as we've been doing this, it's like, how do we include all these elements into a cohesive whole to tell the story?

Because it's so easy to be like "it's a documentary on a Switch cartridge", and it's like no, it's much more than that. And we found and discovered, as we went through this, the amount of flexibility we have to tell stories in this format that we had not even anticipated. As it's coming together, we're getting excited. We're like, "Oh, this is the perfect time to do this, the perfect time to do that."

I get so excited when I watch the feedback from people playing online, where they're going through the story of Deathbounce and then they finally realise they have a finished version of Deathbounce they can play and it's actually really fun. They felt the ups and downs of that whole development, and they get to enjoy that game as it was intended, which is super exciting for me. And it's only because we have all those different aspects, and we've learned from the best out there. Again, people like Limited Run; there's stuff that's been coming out of Japan for years, like the Simple series and Sega Ages, that I think has all been leading up to this. We wouldn't be here if we didn't see all that before.

One of the other things that leapt out at me was how much respect you grant to the player - player, viewer, reader, the audience of this. Because Ka-rah-teka - how was that? I cannot pronounce that word!

[Chris and Mike laugh.]

Chris Kohler: That's one way to do it!

Jordan talks about a lot of different things over the course of this, and he's at Yale so he's clearly a super-smart guy. But you talk about editing, and you talk about montage and stuff like that, and it feels like you had a lot of faith in the audience from the word go. Was that just a given: we're going to be able to tell them this story in a way that they're going to be able to follow, and they will be able to understand and make their own connections between things as well?

Chris Kohler: Well it's always just like you don't know. With Atari 50, that absolutely was the risk. That was the first interactive documentary that we put out. We knew that people really enjoyed the history, the museum-type elements from previous retro collection-type products that we've done, so that was the "let's roll the dice" and let's make it so when you're on the title screen and hit start, you don't go into a menu that says: "Games, Museum, Options, Credits..." We literally just pop you right to the museum and into the timelines. And there was absolutely a chance that it comes out and it gets out to the mass audience who are like, "What is this? I don't want to read! Where are my video games? I can't find my video games." That could have been an issue.

But when that came out and it was instead universally praised for this new approach, that gave us the confidence to say, "Okay, well, now let's do it with Making of Karateka," where you don't even get to play Karateka - we don't even put it on the timelines until the end of the third of five timelines. Let's see if people will go through it and not even get to the game for hours. And then that worked also, so it's really weird - this keeps working.

Mike Mika: One thing that's always proven itself to work every time is to have a good story. It doesn't matter how you deliver it. I'm not a big RPG player but I'm playing through Starfield right now [...] and ultimately it's the story that keeps me going and makes me go through all this stuff. If the story is really tight, it's really compelling, I get absorbed by it. If we're doing our job right, that story is going to be all encompassing. I love that even when I'm playing through it when we're building it, I find myself traversing the timeline and getting lost in it. I'm like, oh wait, I'm supposed to check something out or look for a button in some section, but I just got lost in it again. That part of it is one reason why I think that works.

So Mike, I've been reading a little bit about, and this sounds really sinister, some of the stuff you've done over the years - and Chris I know about some of the stuff you've done over the years. What you've made is I think one of the most complex media objects I've ever seen, in the way it brings together all of these different traditions. Do you think it helps to come from a background where you seem to have had experience of a lot of different types of media and how they work? Does that make it easier? Or more natural I guess is what I'm asking. To put something together which defies categories? Because I know you describe it as a video game but that's not what it instantly felt like to me. I don't know what it felt like. It felt like the weirdest, most magical book I'd ever found or something like that.

Chris Kohler: From my perspective it feels like writing a huge feature article or writing a book, but the end product is a video game. It's extremely lucky that most people on this team basically have some experience on the media side of things, whether that goes back to Next Generation magazine and MySpace. But people understand that. So to come in and essentially create Journalism: The Video Game - it's a very unique situation that we have here to be able to do that.

Mike Mika: I was a film student through college and I always wanted to make movies and documentaries. There's been a few documentaries I've helped produce. It's been a passion of mine over the years. And like Chris is saying, the make-up that we have here: we have people that come from all facets of entertainment. But the one common thing we all have is a love for video games and video game history. For us, it was almost a natural fit to bring all these things in because we've expressed ourselves in all these different ways and it just meshed so well.

Also, there's an immediacy to it because in the past with CD-ROMs, you click on something, it loads, and things are really choppy. But we have technology now to queue things up really fast, so to be able to go from a video and jump right into a game, and then jump right into a 4K scan plus a 16K scan, and zoom around on stuff without any load times: it's something we have as a benefit today that we never had before.

The timeline feels so nice. It feels like you're floating along in a Mercedes. It's got that lovely cloud feel - there's no friction there.

Mike Mika: Yeah we don't want stutters - we don't want anything to just be jarring in any way.

Chris Kohler: We cannot have that. Again, even if you look at previous products that we've done and go through photo galleries: sometimes it takes a little while for that photo to load in as you're going through the gallery. For this, it was like we just have to get past that. We have to have it be totally, totally smooth, because it is, you're right - just zipping through it, it's fun. It's fun if you can make that happen. It's a technical lift. You really need to have very talented engineers working on this, and that is not necessarily something that is visible to the end user, but it really is true.

Mike Mika: There's so many things that we've had to deal with that we never had to deal with before in standard game development. The way we fetch this media, the way it's organised, the expediency in which we want all that information. Normally, you don't have to worry about that, or you put up a load screen in games and you hide it and do whatever. But here, it has to be so immediate. And it goes without saying the tech team has been pulling off some miracles. I don't think people will understand how much work that really is, and that's good because they shouldn't have to look at it and realise it, but so much effort went into that.

I want to ask another impossible question again. So rather than ask you what's next, it's more like what do you think the challenges are for doing more of this in the future? And are there challenges which you feel haven't been solved yet? Obviously one challenge which speaks out immediately to me is that not everyone has kept as rigorous files as Jordan Mechner, who appears to have everything that has ever passed through his life - he's got a copy of it. Are there great games but just the documentation is lost?

Mike Mika: One of the biggest things is we have plenty of stories we want to tell, but there's so much legal work that has to go into finding rights - who owns what aspects of things, what we can and can't share - there's just such a tremendous amount of work to isolate that and conquer that. The other challenge here is it's in some ways a new genre for people we are trying to excite, so it's a big challenge to get people to understand what this is. That's why the naming choice of Making of Karateka was so deliberate, because we're trying to get people to understand this. No amount of PR and marketing or anything we can do really drives it home, until somebody picks it up and actually uses it. Then what we've discovered is that word of mouth beyond that, once people discover what it is, has been fantastic. But again, we're trying to get that audience built up.

Chris Kohler: Ideally what will happen is we get the next game in the Gold Master Series out there, and we get the next one after that. Essentially, the first people that are going to buy it are going to be the people that are bought-in to that particular game because they remember that game, they want to play it again. But then hopefully, after they see that, they're gonna say, "Oh, this is about so much more than these games. I'm going to go back, I'm going to buy the previous ones also." Ultimately that's it. We have to build up the reputation of what the Gold Master Series is so that people can then enjoy the full thing. And then it becomes something like the Criterion Collection, where if something is released in the Criterion Collection, even if you've never heard of that film, you understand that they are saying "this is something that you need to look at". Are we there yet? No. Can we get there years into the future if we really build this up? Yeah.

I'd never even thought about that. I know you did Midway Arcade Treasure, which I've mentioned several times because it's one of my favourite things in the world, but I spent an age trying to work out who owned that stuff now and it's Warner Brothers, I think, which is sort of weird.

Anyway, thank you. I really love what you've done and it's been so lovely to hear about how you put it all together. It's so funny because the thing that made me so interested for Atari 50 and then for this was, I heard someone saying "you've never seen anything like this". It was the same both times. And that was really what they said. They were like, "You are not prepared for this - no one has done something like this before."

Chris Kohler: You know what the challenge is? The challenge is right now we have that advantage of novelty. It's "no one's ever seen this before / this is like nothing I've ever played before". Eventually, once this form becomes something that people expect, then we really have to rise to the challenge of actually making the content in there something that is surprising and advances the form of the interactive documentary. So that's the ongoing challenge.

That sounds like a brilliant problem to have though right? Well look, thank you both so much and have a lovely rest of your day. And thank you Digital Eclipse for Midway Arcade Treasures, it's literally on my desk at work next to my potted plant.

Chris Kohler: The next game is not Eugene Jarvis, but any excuse we ever have to get him back into the studio, I promise you we will.

Mike Mika: I would do a Vid Kidz documentary in a heartbeat.