The Novelist review

Typecast.

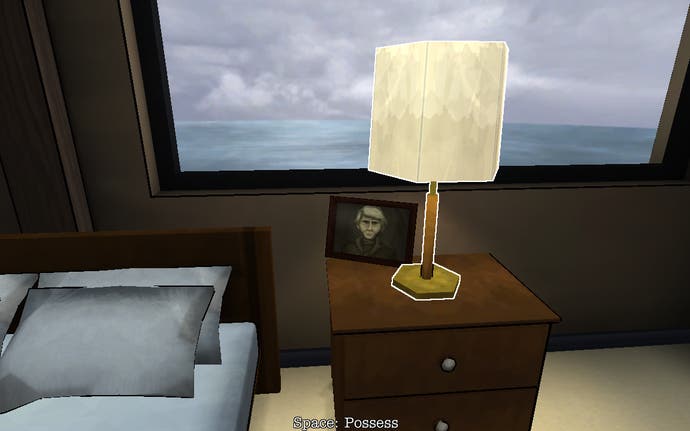

The Novelist is a game where you play as a voyeuristic ghost who possesses household lamps. Lamps you say? Why on earth would a ghost do that? What kind of - okay, okay. Back up. Let me explain.

The Novelist is about a middle-class family comprised of a budding painter and mother, Linda Kaplan, a father, Dan Kaplan, who is the titular novelist, and their cute son who mainly likes Crayola-ing dorky moustachioed pictures of his father. The player takes the role of an incredibly manipulative and nosy ghost who haunts the family's oversized American house. It is your job to read every piece of writing, scour the memories and thoughts of each family member, and then choose their destiny in each chapter by whispering the decision in the father's ear as he slumbers. The idea is to temper their family life, to have them each follow their dreams in a satisfying way.

You can choose whether you play on stealth mode or story mode. In stealth mode, you must snoop from light fixture to light fixture all around the house, pressing space to jump from one to the other. You can flicker a light to distract someone. If you are spotted by a family member as you try to investigate their memories or letters, your persuasive powers toward them become limited, and as a result this alters the outcome. In story mode, you are always invisible to the family, but your ghostly 'walking pace' is extremely slow, so you need to use the light fixtures to navigate quickly and simply without frustration.

I found my ghostly limitations surprising. Learning that as a ghost you have to use stairs is quite concerning. What kind of terrible ghost needs to go down stairs? I want to go through stairs! I want to go above stairs! Things ghosts have done in fiction include: throw books off shelves at people in libraries, vomit up hotel food on guests, haunt paintings and make rivers of slime. Admittedly, all of those ghosts were from Ghostbusters 1 and 2, but my point stands. I feel like the ghost in The Novelist might be depressed.

"I found my ghostly limitations surprising. Learning that as a ghost you have to use stairs is quite concerning. What kind of terrible ghost needs to go down stairs?"

The essential mechanic of the game works like this: the family move in to a vast, empty-feeling, slightly barren house to make a new start. You must guide them through the next few moments of their lives. Melancholic music plays throughout, Lifetime drama style. You, the sad ghost, are already a fixture in the house. You read the trappings of the family's life through letters and stubs of notes, finding clues as to what each family member is feeling. When you have enough clues, you investigate their memories, which manifest as freeze-frame tableaux that you, sad ghostman, float by and discover. You can do this for all three characters, or simply choose one character to investigate who will get their way or 'decision' at the end of the chapter. You're allowed one compromise to another character if you have investigated their life thoroughly enough. Then the game will give you the outcome of your decisions through cut-scenes, showing how your decision plays out for the family.

Initially, this seems like a wonderful concept - the nuance of real-life relationships has been under-investigated by games in the past, and Kent Hudson, the lead developer, nobly approaches the subject matter with guts and chops. But the writing just isn't strong enough to carry the game - the struggling writer who can't find time for his lonely wife and son feels like worn narrative territory, and the text and voiceover parts aren't tonally distinctive from each other, meaning each of the characters just sounds like the same person speaking about dry, everyday problems through three different avatars.

It often feels as though you're just lurking in first-person mode in a sad Sims house, without the excitement of someone wetting themselves, dying in a pool or making out with their own sister. The characters seem more like objects than people. The fact that you have to stealth around in stealth mode just makes the discovery of things in the house much more tedious and time-consuming to get to, and in story mode it's just too repetitive going around the same sparse house environment, again and again, picking up objects from the same locations. At night-time you don't even get to watch the mum and dad do the bad thing.

"As a writer myself, I often struggle with the actual act of writing, but Dan Kaplan seems unable to stop whining about how difficult it is while not even sitting at his desk."

More than this, the constant re-centring of the narrative on the father figure, and the ultimate placing of all 'important' familial decisions on him (you must whisper tomorrow's outcome to the father while he sleeps) seems slightly outdated and occasionally narrow-minded, even in a game named after 'the novelist'. As a writer myself, I often struggle with the actual act of writing, but Dan Kaplan seems unable to stop whining about how difficult it is while not even sitting at his desk. Writers are only writers when they write. Thunder only happens when it's raining. Open that faucet, buddy. You're like that person who sits on Twitter and announces they are writing something amazing that we never hear of again.

The reality is that I couldn't stop myself making a comparison. The Fullbright Company's Gone Home (another indie game made by ex-2K staff) has unfortunately spoiled many aspects of The Novelist for me by being much too good. Gone Home is a game that is also set in a creepy American house. It too can be melancholy and contemplative. It deals with issues of family and with hard decisions. It requires a lot of reading. But Gone Home's developers made it look easy to make the environment interesting, craft characters that are easy to empathise with and have the player feel like they belong in and are a part of the story. This last caveat I have found is incredibly important when thinking about games. You have to feel like you belong. But there's just no feeling that Mr Ghost should really be there.

The Novelist has illuminated for me that many of the best games are about making the player feel as if they belong, or the process of coming to feel as if you belong. Take Merritt Kopas' Lim, for example. You could argue that Lim is about the feeling of not belonging, or suffering in order to belong. But it directly engages with those issues of belonging, making the player feel like this is a process whereby they can belong, or might belong, though it is difficult to do so. This is at the core of games. The narrative has room for us: it includes us or is centred on us in some way.

The Novelist suffers because we are essentially examining a family that doesn't care for us or know about us and we don't really feel an emotional attachment to them. Even in god games such as Populous, the characters below the cursor directly react and relate to things you have just done, indicating they know about your presence. But in The Novelist there's no real reason set up to ever empathise with a white middle-class family that has a huge house, because their problems are never contextualised. In Gone Home, you played Katie Greenbriar, someone who was part of the family, and everything you saw was contextualised through that lens. Katie yearned to speak to her sister - it injected drama, she read about her sister's secret teen passions. It was tinged with humour, angst and sadness. In comparison, The Novelist's ghost lacks that human connection, and instead reads only grumbles written down, adding to your feeling of alienation and sadness.

It's an interesting short experiment in narrative choices, then, but perhaps I'm just missing the point because I'm single, young, childless, and will never be able to afford that house. In any case, I really hope Mr Ghost gets to flip a table over one day or spew some food just once, because he's really earned it.