The occult mechanics of Bloodborne, Cultist Simulator and Pyre

Grant us eyes!

All games are occult. We as players are not privy to the inner workings that define the rules by which we play. Unlike in a tabletop RPG, we're not even aware of the dungeon master's screen that hides the game's secrets and mechanics from us. Still, few games turn the inherent occultism of the medium into their central theme by making us acutely aware of the presence of the invisible screen, compelling us to piece together a mosaic of uncertain knowledge. And only an elect handful does so while invoking age-old traditions of magic and esoteric philosophy.

The most well-known of these is Bloodborne, a game which is notoriously obtuse and unwilling to reveal its hidden depths to the player. While deadly creatures may seem like the most obvious danger, it's ignorance that will be the biggest hurdle to the inexperienced. To glean some of the knowledge necessary for progress, intrepid hunters will either have to study the game's world closely or rely on the information collected by more experienced hunters.

The in-world representation of this striving towards understanding is the resource called "insight," inhuman knowledge gained by laying eyes on or defeating certain enemies as well as consuming items like "Madman's Knowledge" or "Great One's Wisdom". The item description of the latter tells us: "At Byrgenwerth Master Willem had an epiphany: 'We are thinking on the basest of planes. What we need, are more eyes.'"

Only with enough insight will hunters perceive the world as it truly is, and accumulating it will gradually 'change' the world, often subtly, sometimes dramatically as in the revelation of the giant amygdalas clinging to buildings. In the city of Yharnam, knowledge is a blessing, but it's also forbidden and not intended for frail human minds. Some have been driven mad by it, we are told, and amassing large quantities of insight also has its dangers, revealing stronger enemies and making your hunter more vulnerable to frenzy. Occult societies like the Choire or the School of Mensis jealously guard this arcana, conduct secret experiments and rituals that gives them access to dream worlds.

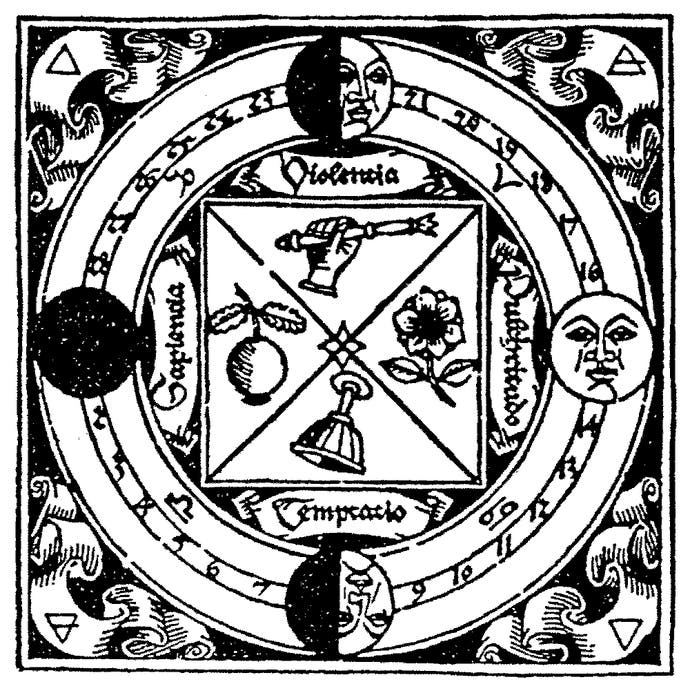

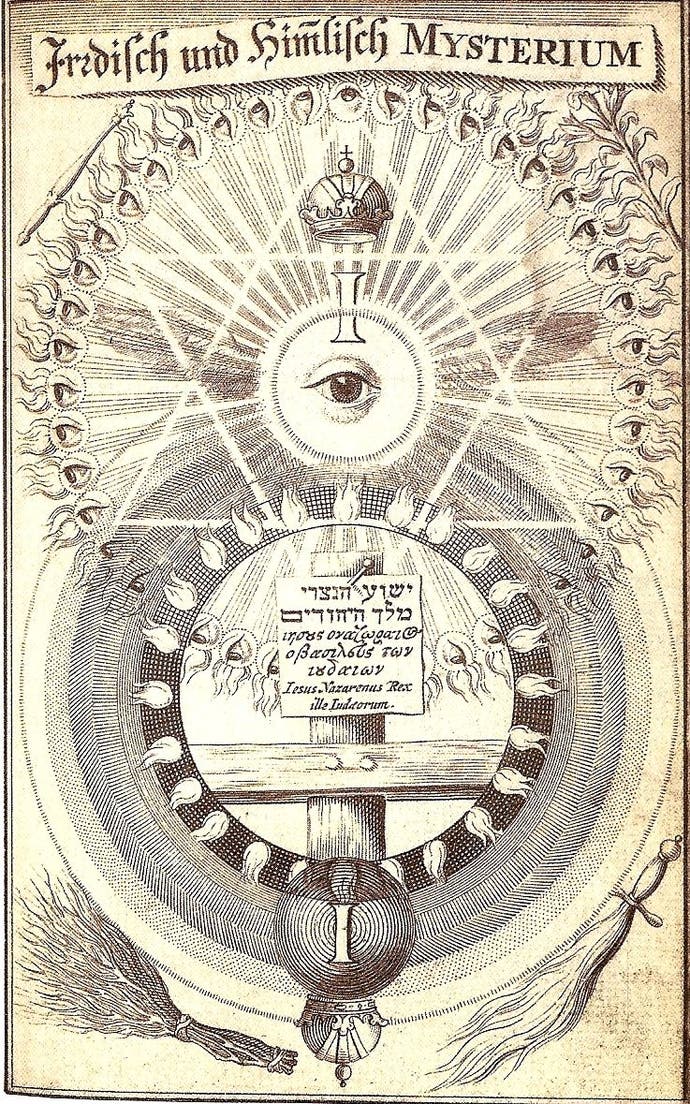

The theme of forbidden and dangerous knowledge is most often associated with the writings of horror author H.P. Lovecraft, but of course, he did not create this trope out of thin air. The tradition of Western mysticism is a long one, with tangled roots that bring together influences from Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Christian and Jewish religion, magic and philosophy. It was in this cultural melting pot that Hermes Trismegistus (the "thrice great"), a syncretic blending of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth, came to be seen as the founder of Hermeticism; a system of thought that shaped esoteric practices like alchemy and astrology or astral magic. The philosophies of Gnostics and Neo-Platonists, with their belief in hidden correspondences within the natural world that could be exploited to bring about desired effects, also had a major and enduring impact on this hermetic tradition. Over the centuries, mystics, alchemists and magicians developed a cryptic system of beliefs, practices and symbolism next to which the notorious obscurantism of Bloodborne seems positively welcoming.

Bloodborne doesn't reference these influences overtly but is still deeply marked by them. Its occult societies with their confusion of science and the arcane, as well as the importance of the moon and its associations with astral magic are some of its more obvious inheritances. The eye, a symbol of insight not just in Bloodborne, also makes an appearance in hermetic illustrations, seemingly answering Master Willem's call for "more eyes".

A more recent game in which the history of mysticism isn't just hinted at is Cultist Simulator. Like Bloodborne, Cultist Simulator is 'Lovecraftian', but here, too, the label seems an oversimplification of a richer history of influences. And like Bloodborne, Cultist Simulator is a cryptic game of experimentation, failure, and gradual insight into the mechanism beneath its surface. To a newcomer, the game seems impenetrable, puzzles wrapped up in mysteries. The aim of the game, simply speaking, is to 'feed' a variety of cards with different esoteric aspects into different nodes, which transforms, combines and multiplies these cards. In this way, we "refine" esoteric lore in the shape of cards, which in turn gives us access to a dream world; the deeper our knowledge, the higher we can ascend the steps of the so-called Mansus, the House of the Sun.

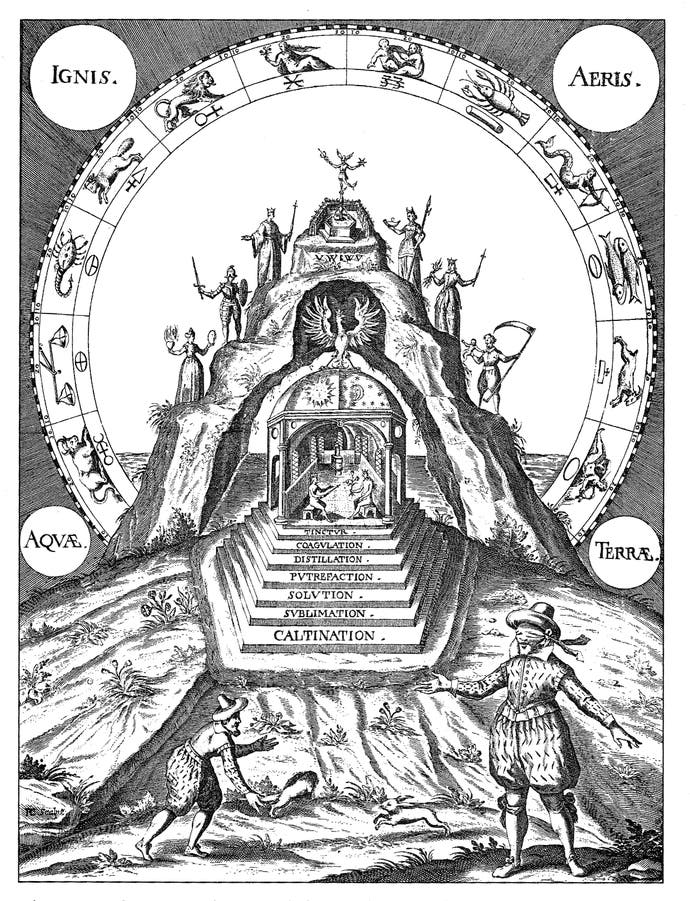

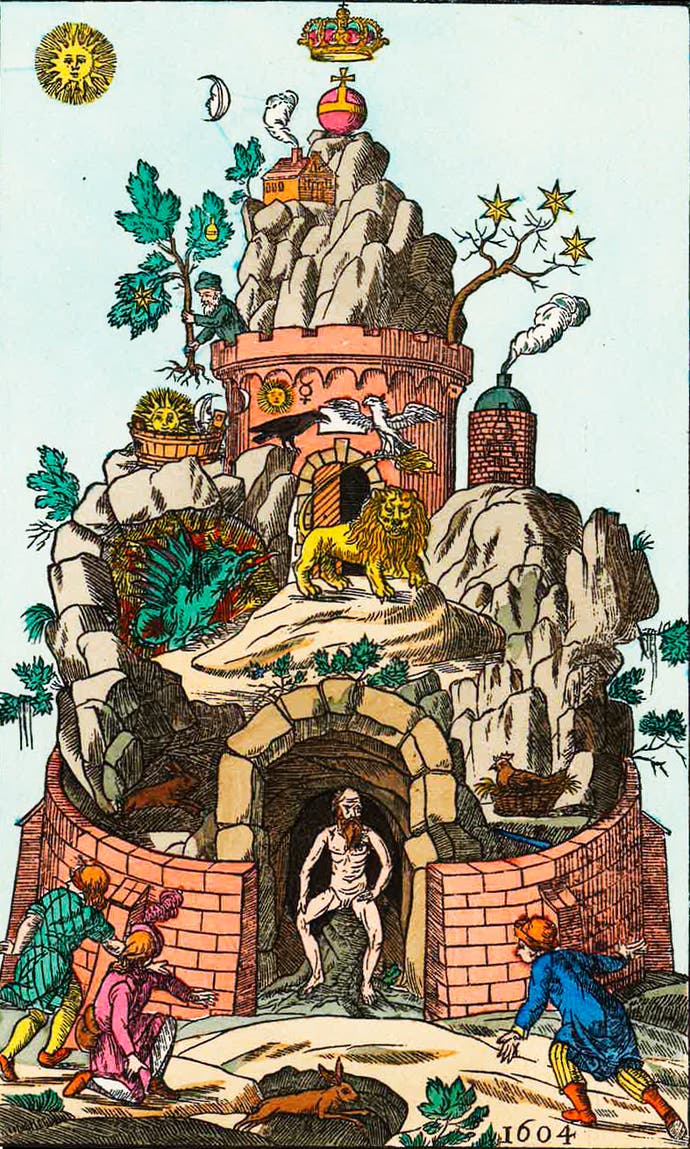

Set in the 1920s, a time that saw a revival and fresh popularity of esoteric ideas and societies, Cultist Simulator isn't shy about the occult tradition of which it is a part. Some of the books we study reference historical esoteric writers like Robert Fludd. The Mansus, with its steps and stages, echoes alchemical ideas about symbolic labyrinths, fortresses, mountains and stairways that represented the practitioners long and arduous path to enlightenment or the process of creating the famed Philosopher's Stone. It is perhaps no coincidence that the mechanics of transforming cards and gradually refining them seem to mimic the alchemical process of transmutation.

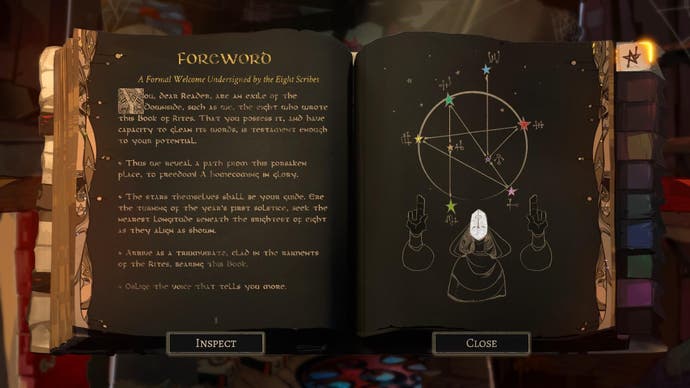

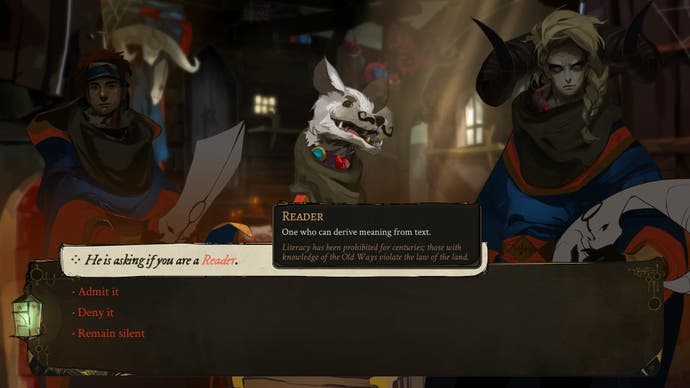

At first glance, a welcoming game like Pyre has little in common with obtuse and difficult games like Bloodborne or Cultist Simulator. But here, too, the exact workings of its systems are unclear in the beginning. While it seems almost simplistic at first, Pyre pulls away the rug from beneath our feet several times, leaving us tumbling down into unsuspected depths. This way, we learn about the cyclical nature of its cosmos, or the tricky rules of the Liberation Rite and the Ascension that leads those exiled to the underworld back into the upper world of the Commonwealth. Just as Bloodborne and Cultist Simulator, playing Pyre could be called an initiation into secret knowledge. So it should be no surprise that we're told that reading is a forbidden art in this world, that our protagonist is only known as "Reader", and that their holy book is full of mystic lore. The stars and constellations, too, must be read and interpreted, as Pyre's frequent use of astrological glyphs illustrates.

Pyre's Ascension, too, resonates with esoteric ideas. Being trapped in a purgatory-like prison world, the exiles long to return to their former home. The Ascension is not just physical liberation, but also spiritual salvation, as its name already suggests. The exiles are 'purified' and their crimes forgiven, and in one of the very last scenes, they are even shown with nimbuses around their heads. Ancient Gnosticism, a major influence on alchemy, was just as obsessed with the individual's return to a divine home. It taught that the human, divine soul had been trapped in or exiled to the corrupted prison that is our flesh and our material world, which had been created not by God, but an imperfect being called the Demiurge. Only Gnosis, that is 'secret knowledge', had the power to liberate the soul and return it back to its true home.

Bloodborne, Cultist Simulator and Pyre belong to the rarest kind of games that not only use the history and symbolism of magic as window dressing, but mimic, elucidate and interpret the deeper logic behind these esoteric philosophies through their 'occult' mechanics. Playing them means becoming privy to hidden knowledge and distinguishing oneself from newcomers and outsiders. The most persistent and knowledgeable of their players produce wiki page after wiki page of cryptic information that, just like your average alchemical tract, looks like pure nonsense to the uninitiated and has no 'real' meaning or use outside its own artificial system. If the result of this is elitist arrogance and pretentiousness in some, it only proves the success of these games to turn players into 'true' magicians and occultists.