The power and politics of Make it Rain

What the latest mobile sensation says about humans and the games we play.

In the strip club, to 'make it rain' is the ultimate act of macho showmanship: a man flicks notes of paper money in quick succession from the top of a wad. He usually aims the money towards a woman, who dances for him while the cash flutters to the floor like so much confetti. In this context - where money, rather than natural attraction talks - 'making it rain' is a show of male braggadocio. The flick of the wrist is masturbatory (and the words carry a plain sexual association, the image of perpetual gobbing orgasm). But more than sex, this is about power and the sexualisation of affluence. Through this act the man says two things: that he has so much money that he can discard it without thought and that, with this money, he can buy the person at whom it's directed.

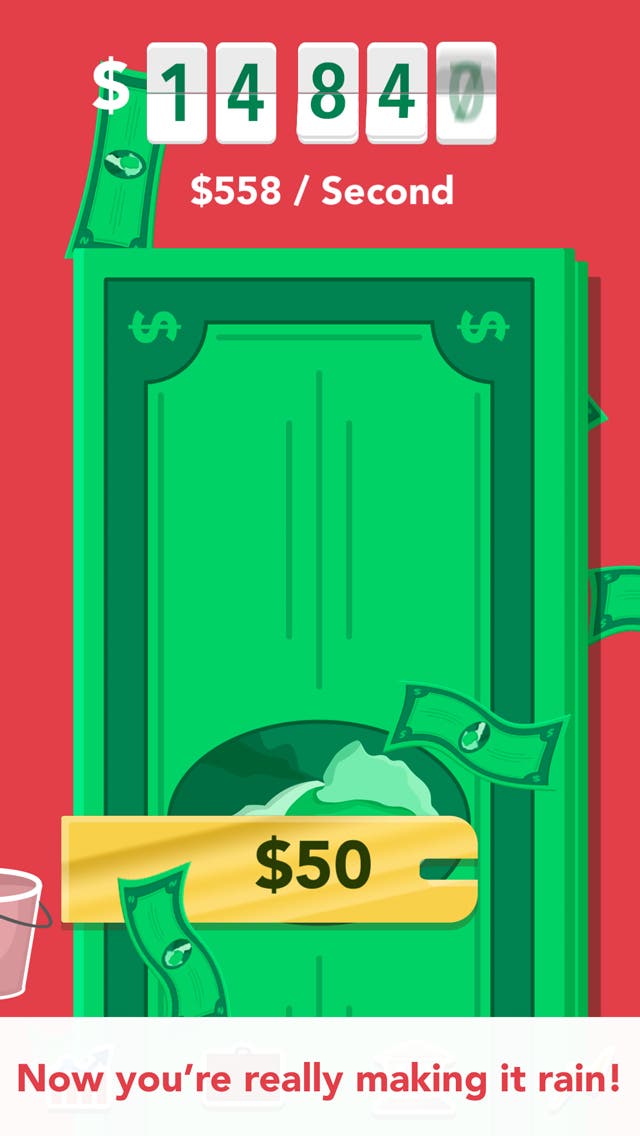

In video game form, Make it Rain: The Love of Money, the current iOS and Android sensation gathering in the cloud, displays a different sort of politics, but one that's no less suggestive. The physical act remains the same: you swipe at a wad of virtual money, causing notes to whoosh from the end of your finger. But here your money isn't aimed at a person. Rather, it's collected in a high-score table. The value of each flicked note is tallied. The more notes you flick, the higher the tally. This is a video game, like so many video games, about the simple human compulsion to make a number rise. But unlike those other video games, Make it Rain wears its capitalist system on its sleeve, while the others - the RPGs, the sims, the strategies - tuck it away in a theme.

Merely flicking money to earn a high score would quickly grow tiresome. So you are encouraged to invest the money that you've flicked into the 'pot' in a variety of different ventures, which enable you to earn money at a quicker rate. Investments fall into one of two types: active or passive. Active investments increase the value of the notes in your wad thereby, in the game's phrase, allowing you to "get more money per swipe". For example, buy a paper round and your notes will upgrade to fivers. Invest in a lemonade stand and they switch to fifties. The outlay for each investment will deplete your cash reserves, but you will quicken your rate of earning. By day two of playing the game, each note you swipe might be worth a million dollars. By the end of the game, when you invest in a banana stand - a nod to the TV sitcom, Arrested Development - you earn $10 billion billion per swipe.

Passive upgrades, by contrast, increase the amount that you earn while the app is switched on but you're not swiping - the rate at which your total earnings tick up of their own accord. Eventually you earn millions of billions per second simply by leaving the app open while you go about your day. You can also invest in upgrades that earn money while the app is switched off, collecting money in a 'bucket' that must be emptied when you next open the game. The bucket has a storage capacity and, when this is reached, the game sends you a notification, calling you back into the financial Skinner box to collect your windfall and make room for the money to, once again, begin to roll in. Your meaningful choices, then, are to decide in which of these three areas you will principally invest, in order to optimise the amount of money you earn in all scenarios.

Every now and again, adversity is thrown into the mix via an FBI investigation into your affairs. You spin a roulette wheel and, if you're lucky, the Bureau will find your accounts in order. If not, you must either pay a bribe (after the first bribe, these must be bought with real money) or incur a penalty, whereby your rate of earning is slightly decreased. But this peril is something of an afterthought; the game's natural rhythm and theme is about making virtual money as quickly and efficiently as possible. As the increments increase, the numbers involved begin to lose their significance, allowing us to feel what it must have been like to be a stock market trader in the months leading up to the financial crash of 2008.

If this were pure satire, it could be devastating. But Make it Rain forgoes (or, depending on your perspective, intensifies) any mockery by including genuine advertisements for real-world financial companies and products during play. There's the company that will pay money for your old gold. There's even an advertisement for Hargreaves Lansdown, one of the most prestigious 'investment shops' in the UK, inviting you to download the company's iPhone app in order to manage your share portfolio. Like this game? Why not play with the real thing?

Make it Rain offers a taste of capitalism's soaring highs without any of the risk or ingenuity

Make it Rain is well designed, but it is design without challenge. It shares similarities with Facebook compulsion loop software such as Mafia Wars and even last year's excellent web game, Candy Box. But, while Candy Box shares Make it Rain's compound interest play loop, it features many more opportunities for player expression and, later in the game, for skill. By contrast, Make it Rain simply offers a taste of capitalism's soaring highs without any of the risk or ingenuity. Tragically, there is no endgame. Buried in the options menu is the opportunity to reset your earnings back to zero; once you've scored the highest number, there's nothing left but to do it all over again.

The most wounding criticism that can be levelled at the video game medium is not the one that has filled the headlines through the years - the one about how games can inspire violence or turn good kids bad. It is, rather, that games give humans a sense of accomplishment that's so chemically authentic it can distract us from true accomplishment. What great works have gone unmade, great discoveries gone undiscovered, great lives unlived because of the opiate of the video game, with its potent imitations of achievement? Make it Rain gives us the sense of having lived the trajectory of a capitalist, from poverty to unfettered wealth - the achievement of affluence scaled up to ludicrous, Bill Gates-esque proportions. But it's a vacuous achievement, won through mild endurance rather than skill or interest. It makes clear the hollow heart of some video games. It is, in that sense, a cautionary game. Moreover, while we play at getting rich, the game's makers are, reportedly, becoming enormously wealthy themselves. This is both the game's genius and its tragedy.

Each time that you open Make it Rain, you're presented with a biblical quotation related to money. These are those familiar cautionary warnings: 'money is the root of all evil', 'it's easier for a rich man to pass through the eye of the needle than to enter the kingdom of heaven', and so on. They are flippant digs, perhaps, at the game's players. As I stood in a queue at the supermarket with my daughter, idly flicking at my phone's screen to 'make it rain', she asked me what I was doing. I sheepishly showed her the game. After a moment, she cocked her head and said: "Let me get this right. You flick the screen to make the number go up?" I nodded. "And how is that fun?" To paraphrase another biblical saying: sometimes, in order to see the truth, you just have to look at things through a child's eyes.