The Rise and Collapse of Yoshinori Ono

From the archive: How Street Fighter gave the Capcom director a life and then almost took it away again.

Every Sunday we bring you a selection from our archive, a feature you may have originally missed or just maybe would like to read again. This week, it's Simon Parkin's profile of Capcom's Yoshi Ono, the hard-working producer behind the revival of the Street Fighter series. The piece was originally published in June 2012.

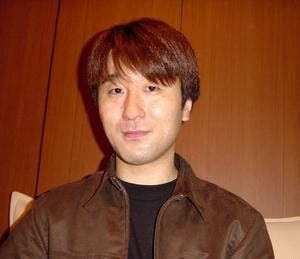

Rumours of Yoshinori Ono's death have been greatly exaggerated. As we sit together in the lobby of a Roman hotel, three weeks after his release from hospital, Street Fighter's creative custodian has a healthy red glow to his chubby cheeks while the irrepressible smile that has made him the approachable face of his employer Capcom in recent years is undiminished.

But appearances can be deceiving and Ono's sudden illness in April 2012 was both unexpected and serious. His employer's reluctance to issue a statement only compounded rumours. Indeed, his attendance here at Captivate, the company's annual video game showcase, was entirely unexpected, even to many of Capcom's own employees who remain as much in the dark as to the truth of the matter as Ono's fans do.

"So, what happened?" I ask.

Like all Ono's weeks of late, it had been a busy few days. Following the gigantic success of Street Fighter 4 in 2008, Ono was granted full responsibility for both the creative direction and marketing of Capcom's fighting games. After the release of a key title, his schedule becomes especially gruelling, making not only mental demands as he works to appear fresh and in high spirits for each new group of journalists he must address or fans he must hype, but also physical ones as he flies through time zone after time zone to each appearance.

The final leg of his most recent promotional tour ended in Singapore and Ono arrived back home in Osaka late on a Sunday night. He fell into bed, trying not to think about the alarm that would rouse him for a new week's work in a few hours.

"I woke up and walked to the bathroom," he tells me. "When I opened the door the room was abnormally steamy. Stranger still: the steam was rising. It kept rising, up and up, and I didn't understand what was going on. It was like I was suffocating. Then, when the steam reached my head level I passed out cold and collapsed onto the tiles."

"What happened then?"

"My wife was at home and heard the crash. Later she told me that she ran into the bathroom. There was no steam, just my body on the floor. She called an ambulance and I was rushed to hospital. When I came to, the doctor told me that my blood acidity level was on par with someone who had just finished running a marathon. He asked me: 'Ono-san, what on earth you been up to?' I told him that I woke up, went for a bath and simply passed out. He didn't believe me. I guess I have been working too hard. You could say my health bar was on the dot."

"Steam chip damage?" I quip, and Ono laughs hysterically. He laughs a lot: a hyperactive titter that punctuates his sentences like a court jester. He loves to make jokes, to see people laugh. Even when he's talking about falling into a near coma he sugars every sentence with generous laughter. Often it's unclear if he's masking true emotions, or whether he only sees the funny side to life's setbacks.

"When I came to the doctor told me that my blood acidity level was on par with someone who had just finished running a marathon. He asked me: 'Ono-san, what on earth you been up to?'"

"Capcom doesn't allow a trade union or any sort of worker movement you see," he says, giggling. "So if I complain I will probably get sacked. You have to say it for me, OK? I want you to write: 'Capcom overworks Ono'. That's your headline."

I shoot the PR guy an apologetic glance. He sighs and looks to the ground. Ono, catching our interaction, turns to him and says, with that impish grin: "Just you wait. It will be you passed out on the floor one day."

"That's not quite true though is it, Ono," I say, when the giggles die down. "I heard that Capcom was eager for you to stay at home for this trip; to take it easy?"

Never trust an interviewee who tries to write your headline for you.

"Whoever told you that is lying," he retorts, his smile shifting down gears to a rare frown. "The situation is the complete opposite. Nobody told me to take a rest. When I returned to work, Capcom didn't even acknowledge that I had been in hospital. There was no change in my schedule. I was at home for an entire week before the doctors allowed me to return to work. When I returned to my desk there was a ticket to Rome waiting for me. There's no mercy. Everyone in the company says: 'Ono-san we've been so worried about you.' Then they hand me a timetable and it's completely filled with things to do."

Ono has, in the years following Street Fighter 4's launch, become the face of the company, adding personality and humour to a publisher hitherto best known for the departure of its star game makers, Shinji Mikami, Hideki Kamiya and Keiji Inafune. I wonder whether Ono's collusion in overworking is down to his feeling the pressure to be the face of the company, its mascot?

He chuckles with pleasure at this idea: "Thankfully there's no pressure. I naturally like interacting with people, talking, laughing, I enjoy Twitter. People always write to me saying 'Capcom sucks' or 'Ono sucks' and so on. But there's a positive in that criticism because it means that people care and are interested in what I am doing. And I do listen to the community and its suggestions. It's not like they are going to stab me, right? As long as nobody stabs me I am happy to receive criticism."

This desire for attention defined Ono from a young age. At junior school, he was a geekish boy, fascinated by computers and programming. "Every week I would visit a large bookstore in the centre of town in order to read their programming books," he explains. "It had to be one of the major bookstores, as the smaller ones didn't carry these publications. They were quite rare. Anyway, I would read three to four pages and memorise them. We didn't have camera phones back then, so I had to hold it all in my head. Then I would run across the street to the McDonald's and write the code down in my notebook. When I had it all down, I'd go back in and repeat the process.

"I went home, made a demo tape of my guitar playing and sent it in. A few days later Capcom invited me to an interview for the job. On the evening following my interview, I had a call saying: 'You start next week'. These days there's a lot more process, but in 1993 it was that straightforward..."

"But when I started high school I found out that being this geeky guy who loved memorising lines of code wasn't very popular with girls. So I decided to learn an instrument. Girls go to concerts and scream at boys in bands. I wanted that. The thing is, I chose keyboard for my instrument. I didn't realise keyboard is the lamest instrument of all in the band. Keyboard players are always in the background - almost as bad as the drummer. So even in my high school days, when I was performing music, I had no luck with girls..."

Despite Ono's musical awakening in high school, it was his love of computers that drove his decision to study architecture at university. "My ulterior motive for applying to university was computers," he explains. "I wanted to join a faculty where there was a super computer available to me. Back then, there weren't many universities offering this kind of access. So I chose an architectural mechanics course, as it afforded students access to a super computer. As soon as I had that, I didn't care about architecture any more."

It was during this time that Ono taught himself to play guitar ("my university life was much more fruitful than my time at high school in terms of girls") and began to specialise in rendering fluid in 3D graphics programs. "I wasn't writing games at this time," he says. "But I was interested in graphics and interactivity. In the late 80s rendering fluid was a very high tech thing; very difficult. That was my focus and speciality. On my fourth year I was doing well so my mentor told me I could stay on to do postgraduate work if I wanted."

While Ono was deliberating whether to continue his studies or begin working instead, he read an advertisement in a magazine for the position of composer at Capcom. "I knew the name because I played a lot of Final Fight in the arcades," he recalls. "I thought: 'Wow. So I can make games, create music and get paid? This is going to be amazing. So I went home, made a demo tape of my guitar playing and sent it in. A few days later Capcom invited me to an interview for the job. On the evening following my interview, I had a call saying: 'You start next week'. These days there's a lot more process, but in 1993 it was that straightforward..."

It didn't take long for Ono's idealistic expectations to be shattered. "When I first joined I imagined I was entering this lucrative world where a composer could create art uninterrupted. In reality I was limited to 2KB data for all of the music I created. Unlike today, game music wasn't recorded at that time. It all had to be programmed by hand. And in order to keep file size to a minimum, all the music was written in binary; the shorter the string, the better. It was almost like encryption. I spent all of my time sitting down, figuring out my formulae for my code. It was far from what I had dreamt of."

Ono's first project was a wrestling game called Muscle Bomber. Soon after this he had his first contact with Street Fighter, the one-on-one fighting game series that would come to define his career in later years. "My second project was creating a port of Street Fighter 2-X, converting music by handwriting binary," he explains. "I lived out of the office. I'd work till 2am, take a nap and then start writing code again at 7am. I barely went home for two years."

"After I passed out, I was thinking in the hospital: there are so many people at Capcom that, over the years, have disappeared at one time or another. Suddenly, in that bed I understood what happened to them... The day after a game is finished and goes off to manufacture there are ten empty desks, their previous occupants never to be seen again."

This gruelling work was just a taster of what Ono would encounter on his next project. "Street Fighter Alpha was developed for CPS2, a very powerful arcade motherboard. But due to political reasons we still had a whole load of its predecessor, the CPS1 board, in our warehouses. So the company decided the game should be available for CPS1 as well as CPS2. In contemporary terms, CPS2 is like a PlayStation 3, while CPS1 is a PSone: the technological gulf between them is massive. I was ordered to port all of the music back to CPS1 in no more than three weeks. That was hell. Thinking about it now, even back then Capcom was very good at squeezing people to the last drop of their blood to get work done."

That wicked smile again.

"After I passed out, I was thinking in the hospital: there are so many people at Capcom that, over the years, have disappeared at one time or another. Suddenly, in that bed I understood what happened to them... The day after a game is finished and goes off to manufacture there are 10 empty desks, their previous occupants never to be seen again."

We laugh and I shoot the PR guy another apologetic glance. It wasn't easy for him to organise this interview: his seniors were reluctant for Ono to speak to any journalist so soon after his illness and with the sharp accusations being thrown around, I figure his own job as chaperone could be in jeopardy.

But Ono is a far smarter man than the scattershot front might suggest. Despite his relatively high position within the company, these outrageous attacks on his employer are too sustained and calculated to be a momentary lapse in judgement and, while he is clearly angry for having worked himself into hospital, there's a smile and quickness behind the eyes that suggests he is fully in control of all he's saying. He clearly takes pleasure in his irreverence, even if there is a genuine seed of resentment at its core.

Still, I wonder whether his experiences of overwork have made him more sympathetic with the junior members of his teams. "Quite the opposite," he says. "I am a middle-aged man so I am saying to the younger ones: 'You have the energy, the stamina, the get-up and go. You should be doing better.'"

Despite Ono's university background in creating fluid dynamics, he remained working in the sound team at Capcom throughout most of the 1990s. I ask him how the jump to his managerial role as producer came about.

"While I was working on Street Fighter 3 I began to manage human resources in terms of the external and internal sound teams," he says. "We weren't called 'producer' then, but that's what the role amounted to. At that time, Keiji Inafune was closely watching how I worked and asked me to manage all sound for Onimusha 1, 2 and 3. I co-ordinated and managed all of the sound and music talent at that time. The higher-ups saw that I had a talent for managing people and projects and they came to me to suggest that I try producing an entire title."

"When Third Strike came out R&D didn't really consider sales back then. We weren't as marketing orientated as we are today. We just wanted to make the best game and wanted to please our most hardcore fans."

While Ono's career began to take off within the company, there was still a nagging regret that he couldn't shake. "I played Street Fighter throughout my life. I was in the Street Fighter 3: Third Strike team when we disbanded and the series was laid to rest for a whole decade. As a result I've always had it in me - some feeling of regret that I was a part of ending the legacy of Street Fighter. A guilty conscience, I guess you could say."

Street Fighter, Capcom's defining game series that originated in 1987, had struggled to maintain an audience past the mid-'90s. At one time it was king of the arcades, drawing competitors to battle it out in 60-second bursts of speed chess, dressed up as bar-room brawl pixel fights. But following the release of Street Fighter 3: Third Strike in 1999, declining sales meant Capcom decided to lay the series to rest.

"When Third Strike came out R&D didn't really consider sales back then," Ono explains. "We weren't as marketing-orientated as we are today. We just wanted to make the best game and wanted to please our most hardcore fans. That's what drove us. Obviously, in terms of sales it didn't pay, so the company couldn't invest in a sequel with a decent rationale. Not only that, but we were adamant we had made the epitome of the fighting game with Third Strike. So from the company's point of view, if the team is stating that it cannot do any better combined with a lack of sales, it's a complete story and it's time to move on."

It was this guilty conscience that inspired Ono to write a design document for a fourth entry to the Street Fighter series immediately after he was promoted to producer. "I was working on Onimusha 4 and during that time I repeatedly submitted my proposal for a new Street Fighter," he says. "The company kept telling me: 'It's a dead franchise. It doesn't make any money. We have series that make money like Resident Evil and Onimusha. Why bother with a dead franchise?'"

"Eventually I was given a small budget to create a prototype. That wasn't really down to me pestering my superiors so much as all of the journalists and fans started making a lot of noise and pressuring Capcom. This was a strategic plot on my part. I had been asking all the journalists to make noise about the series when out and about. I would always tell them that it was their responsibility to tell Capcom, not me as I don't have the power. Journalists and fans have the power to move Capcom - not producers. With so many voices crying out for a Street Fighter game Capcom could no longer ignore it any more and so they gave the green light for a prototype and they asked me to create it. It's a miracle that happened after a decade..."

"There have been rumours saying Ono is dead or retiring. None of that's true. I want to support the next generation of fighting game."

However, it was a reluctant project for the company. "Until the day of release, Street Fighter 4 was an unwanted child," Ono says, his tone at once sad and defiant. "Everyone in the company kept telling me: 'Ono-san, seriously why are you persisting with this? You are using so much money, budget and resources. Why don't we use it on something else, something that will make money?' No-one had the intention of selling it, so I had virtually no help from other departments - they were all reluctant, right up to the day of release."

I wonder whether this is where the key to Ono's recent illness can be found. To Capcom, Street Fighter 4 was an unwanted baby. Ono was fully responsible for its conception, gestation and birth. Without him Street Fighter would still be buried in the graveyard of so many arcade games. He was undeniably responsible for its resurrection. Could he also believe he is responsible for its continued survival?

He bats the question away: "Calling it a baby seems a little over-dramatic perhaps. It might be better to describe Street Fighter 4 as the crystallisation of all of my tears, blood and effort. I'd call that passion and so yes, Street Fighter is my passion. That's all I'd say."

I sense I have hit a nerve and, perhaps, a truth. Ono's calls for Street Fighter's revival were ignored by the company. He was forced to leverage fans and journalists to force Capcom's hand. Even then, nobody at Capcom believed in the project but him. That's why he identifies with the fans so much: they share his passion, a passion that his company long lost. That's why he worked himself into a hospital bed: not for financial gain, but because the fans are his community, his people, and if he doesn't take his games to them, nobody will.

There's a lull in the conversation. Then Ono puts his own words to my thoughts.

"What fuels my passion is the community. In my philosophy, Street Fighter is a game, but really it's a tool. It's like playing cards or chess or tennis: it's really about the people. Once you know the rules it's up to the players to put themselves in the game, to choose the nuance of how they play and express themselves. I think fighting games flourish because it was this social game. If it had been a purely single-player thing, it would never have grown so popular.

"My aim is to construct a universal community. Back in the arcade days you had a small neighbourhood town community playing Street Fighter together in the arcades. Then the next town had its own community. But they were isolated from one another... With Street Fighter 4 my aim was to bring these communities together with the online system. I succeeded and now I want to create the 'Order of the Street Fighter', an online community where people can meet to play fighting games. They can engage in any game, it doesn't matter which one."

"The only rule is that every player has to pay me one Euro," he says, smiling. "This will be my pension."

We laugh but what Ono says next makes clear that he is not joking. "I want to sit in my office and plan this out. There have been rumours saying Ono is dead or retiring. None of that's true. I want to support the next generation of fighting game. It's my job. It's my calling."

It's true, then. Ono sees himself as the saviour, not only of Street Fighter but of an entire genre. The only question is whether he will have enough energy to save himself as well.