The Shareware Age

A brief history of the PC's first reinvention.

Sharing is caring

You've probably heard the term bandied about in relation to Doom and Wolfenstein 3D, but shareware's roots go back far earlier. The concept originally emerged (accounts vary, but probably no earlier than 1984) as a response to the high price of commercial business software, as well as a tacit acknowledgement of the tendency of computer enthusiasts to happily copy, swap and pass around software they liked regardless of limitations imposed by the license.

Shareware authors would release complete versions of their programs for free, uploading them to popular Bulletin Board Systems (from where they would be picked up by mail order companies - being sent parcels of floppies was still the preferred option for the majority of users who weren't sold on slow, expensive WarGames-style modems). If you obtained the program, tried it out and found it agreeable, you were encouraged to send a donation to the developer. In return you might receive product support and updates, additional programs, source code, or perhaps just the warm fuzzy glow of having supported the underdog.

While this infrastructure may not have been far removed from the catalogues used by 19th Century homesteaders to order feed, furniture and wives, the appetite for affordable PC software was so great that users embraced the concept immediately and shareware authors found a steady trickle of cheques coming in. A few programs became very successful and sparked a gold-rush among bedroom coders much like the current brouhaha surrounding the iPhone.

At first shareware vendors viewed games as a sideshow to the main event - an added bonus for people shopping for desktop publishing and book-keeping applications rather than a money-spinner in their own right. The games disks they offered (given evocative names like "Arcade Games 1?) collected together tiny, unofficial versions of golden age coin-ops (Space Invaders, Centipede, Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Pengo) or mainframe games (ADVENT, SpaceWar, Nethack, Star Trek). Most of these were developed by hobbyists (or in a few cases as promotional items for tech companies) and few made anything more than half-hearted solicitations for payment.

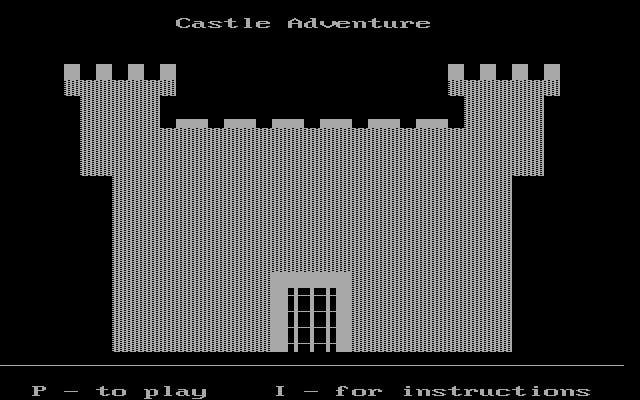

Among the waves of clones were a few intriguing original efforts. Flightmare involved piloting a light aircraft around a post-apocalyptic desert, shooting down gangs of planes and bikers before they could reach your factories. Dracula in London presented Bram Stoker's story as a turn-based adventure styled after an after-dinner board game (going as far as to suggest that the different characters in the party be controlled by different players). Slightly less pretty (in fact, possibly one of the most visually spartan games ever made) was Castle Adventure, a surprisingly competent mash-up of Zork and Atari's Adventure, with only the quirky spelling hinting that the author was only 14 years old.

All of the games mentioned thus far either used "text mode" (ANSI) graphics (a technique introduced to a new generation by Dwarf Fortress) or four-colour CGA, and as such are compatible with virtually every PC ever made.

Going professional

These early shareware games were a pleasant enough diversion, but they weren't exactly buying their authors lunch. The standard shareware model may have been successful for 'serious' software and utilities, but game developers quickly found that while gamers were happy to oblige with the sharing part, they were less inclined to pay up for games that they'd played for a while before casting aside. Devs needed to create an incentive to pay, but artificially removing features from shareware applications was frowned upon.

The solution to this dilemma arrived in 1987 with the release of Kroz. This was a vaguely Rogue-like maze game written by Scott Miller and published by his company Apogee Software (who would later become 3D Realms, best known today for spending 12 years working on Duke Nukem Forever). The game was divided into 'episodes', the first being offered as a freebie, with additional bundles of levels available on registration. Unlike modern game demos, the free episodes offered under this model were effectively fully-fledged games in their own right, typically offering several hours of gameplay, most of the game's features (weapons, enemies, powerups and so forth) and a climactic (albeit usually cliffhanger) ending.

The episodic model quickly caught on. The steady income that it provided would allow for investment in more ambitious projects (and in some cases, garagefuls of sports cars). Over the next few years Apogee would go on to become the leading brand in shareware with a string of hits which successfully kept pace with rapidly-evolving PC technology.

By the end of the 1980s PC gamers were starting to feel strange instinctive urges telling them that they should spend more money to get better graphics. At the earliest opportunity, shareware developers started to make use of the Extended Graphics Array (EGA), introducing the concept of the 'minimum spec' to PC gaming in the process.

EGA allowed 16-colour graphics, but was notorious for having a fixed palette which lacked even a vaguely acceptable approximation of a skin tone, resulting in a proliferation of games with unfortunate puce- or orange-faced protagonists. The move to EGA coincided with a trend for mascot-driven platform games. Initially these were flick-screen, platform-puzzle affairs similar to earlier games on the Apple II (such as Crystal Caves, Secret Agent and Pharaoh's Tomb).

Conventional wisdom held that smooth, full-screen, console-style scrolling was beyond the reach of the PC's weedy graphics chips. Conventional wisdom didn't know it was about to run afoul of John Carmack, and was going to have to get used to it happening a regularly over the next few years. Commander Keen, developed by id Software and released through Apogee in 1990, elegantly solved the scrolling problem and provided an engine which was used for six main episodes as well as other Apogee games.

For the first time PC gamers were being offered console-style action in a recognisable (if not particularly pretty) form. These games were progressively easier to market (being perfect fodder for magazine cover disks, for example) and provided good fuel for Apogee's episodic model. They would continue cranking out 16-colour action games for the next few years, including titles such as Major Stryker, Bio Menace, Monster Bash and Duke Nukem I and II.