"The Spectrum was bigger than all of us": the people behind the legend celebrate its 40th anniversary

Rubber love.

The Sinclair ZX Spectrum is 40 and Eurogamer isn't the only one celebrating the occasion. Such is the popularity of the iconic micro – particularly in the UK where it achieved sales of five million over a ten-year period – that its milestone anniversaries always attract mainstream coverage. Kay Burley is probably taking about the ‘rubber-keyed wonder' right now.

So while we all wallow in pleasant nostalgia, how do those that were actually involved in the development of the computer feel about it 40 years on? What impact has it had on their lives – and from their perspective, the lives of others? We got in touch with six of the original team to ask them.

Richard Altwasser joined Sinclair in November 1980 and designed the Spectrum's internal hardware, including the custom ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array) that sits at the heart of the computer. He later managed the design of the Spectrum Plus 2.

John Mathieson was involved in the launch of the Spectrum in April 1982, having joined Sinclair four months earlier. He supported the Spectrum throughout its production, working on the many PCB revisions, and designed the Interface 2 gaming add-on.

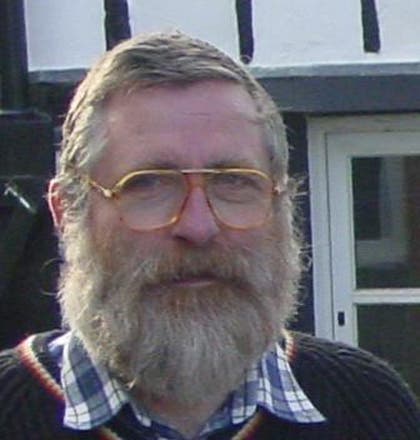

John Grant ran Nine Tiles, the small company that Sinclair contracted to create a version of the BASIC language for its computers. John wrote it initially for the ZX80 (in just 4Kb!) and this was later expanded for the ZX81 and Spectrum by Steve Vickers.

David Karlin was an electronic engineer and chief designer of the Sinclair QL, the 32-bit business computer that launched in 1984. He was heavily involved in the manufacturing side of the Spectrum.

Cliff Lawson was an Amstrad employee who worked on the CPC and PCW lines. Thanks to his familiarity of the Locomotive disk operating system he was involved in writing the disk drive code for the Amstrad-produced Spectrum Plus 3.

Rupert Goodwins joined Sinclair in early 1985 as a software engineer and developed the system software for the Spectrum 128. He moved to Amstrad following the Sinclair buy-out in 1986 and updated the ROMs for both the Spectrum Plus 2 and Plus 3.

Two notable omissions are Rick Dickinson, who conceived the singular look of the Spectrum, and Sir Clive Sinclair himself. Though both are no longer with us we remain greatly indebted to their contributions.

As the Spectrum celebrates its 40th anniversary, why do you feel that it's so well remembered? It has to be more than just nostalgia hasn't it?

Altwasser: I feel it's well remembered for several reasons. It was the most successful of the many personal computers from that era and therefore created the home computing market in the UK. It became an icon. Many users wrote their first code on a Spectrum, and then went on to careers in computing, so it impacted not just individuals but created a whole generation of coders. Plus, many businesses grew on the back of the Spectrum selling software and peripherals. Many entrepreneurs arose out of the success. Of course many more will remember playing games and the Spectrum will have formed an important role in their experience of life in the 80s and early 90s.

Mathieson: Games. The Spectrum was the first widespread home computer for gaming. Computers and game consoles got better later – much better – but it really was the first system that was good enough for games in the UK. It changed everything for a lot of people.

Grant: If by ‘well remembered' you mean lots of people being aware of it, well Clive Sinclair was a more newsworthy figure than [Acorn's] Chris Curry or Hermann Hauser. We all remember the C5 don't we? If you mean ‘remembered with fondness' it must be the software. It was one of the biggest sellers mostly because there were more games available for it.

Karlin: We lived in a world where computers were inaccessible, room-sized machines owned by giant companies. Computers like the Commodore Pet, Apple I and II, and, in its own way, the Sinclair ZX81, started the process of changing this. But when the Spectrum arrived it hit that magic point of being very capable and extremely affordable, to just about everyone of any class. For countless thousands it was their first experience of computing and games.

Lawson: I think you had to be there at the time. In 1980 my twin brother and I pooled our resources and bought and assembled a Sinclair ZX80 from a kit. It was very limited so imagine the revelation when our Dad later brought home a Spectrum and a copy of Manic Miner. It was like nothing we'd experienced before. We played Manic Miner to death and I can still get through most of 20 levels almost 40 years later. But it also had that same token programmable BASIC previously used in the ZX80/81. I learned a lot that would help me in the following 10-15 years doing Z80 assembler professionally at Amstrad.

Goodwins: For many people it is nostalgia, and none the worse for that. The 80s gets a lot of stick but it was a fiercely innovative decade with some amazing music and the birth of digital in the home, and the Spectrum was one of the first devices to be affordable to many. Every generation has its own music, its own fashions, its own culture, but the Spectrum marked the first time a generation had its own digital ecosystem. It had no past, no roots in our parents' culture. It was the gateway to the future and it was so much fun.

What impact do you feel the Spectrum has had on the UK computer and games industries?

Altwasser: From my own experience it has been clear that using a Spectrum as a youngster – particularly the ability to progress quickly from opening the box to getting code working on the screen – was a spark that initiated a career in computing for many people. It's also self-evident that the many providers of Spectrum software, particularly games, were greenhouses for learning the techniques of animated graphics. A wealth of UK technology expertise has since grown and developed as the hardware platforms have progressed.

Grant: Along with the ZX80/81 it was many people's introduction to programming, being quite a lot cheaper than other computers.

Mathieson: The Spectrum was a real computer. People could write code on it, progress to writing games, and generally develop their skills. And all this came naturally because the system was very open and very simple to learn. Neither consoles nor computers have this quality any more.

Goodwins: For techy types, it is more than nostalgia, it was a complete course in computer technology. You cannot look at the UK games industry and not find its roots in the 80s 8-bit wave, and of that wave the Spectrum was the most democratic, the most widespread and the most revolutionary. It had just enough capabilities to be rewarding to the inquisitive, but not so many that it seemed inaccessible, or too easy just to enjoy the gaming experience. You could bring one home from WH Smiths and a month later be taking your first dabble in simple machine code that made the screen ripple in psychedelic colour. If that doesn't hook you as a geeky teenager, nothing will.

Lawson: The impact the Spectrum had on the home micro market was immense. It set a level of features that any competitor would need to match. It was a glorious time to be involved in micros as almost every month saw something new being launched. I remember my brother getting interested in this new machine from the ‘crap hi-fi' company Amstrad. So he bought a CPC464 that I used for a bit during the summer of 1984. Little did I know I would be getting a job with Amstrad that following October and then working there for the next 25 years. The CPC was intended to be a UK/Euro Commodore 64 rather than trying to capture the Spectrum market.

Karlin: The Spectrum had personality. The design compromises born out of cost-driven necessity turned into endearing quirks – the spongy keyboard, the blocky colour, the slightly-too-small size – and that's down to the intuitive genius of designer Rick Dickinson and of Clive himself, both late lamented. And somehow, that quirkiness infected a horde of software developers who multiplied it manifold – necessity being truly the mother of invention.

How gratifying has it been for you, to have contributed to something that's so special to so many people?

Altwasser: I've always have been busy in my career, family life and other interests, and have rarely looked back, always forward. So this isn't a question that I've considered much. It is humbling to think that my efforts at an exciting time early in my career might have contributed to so many gaining a love of coding that pointed towards a career in computing. And to have provided millions with hours of fun and entertainment.

Karlin: For me, what I want most out of my career, whatever the field and whatever the product, is to touch the lives of as many people as I can. Having been part of the Spectrum story fulfilled that desire in no uncertain terms. A lot of people are very different today as a result of what we did. I can't ask for more.

Mathieson: It is gratifying to have worked on this, but the ZX Spectrum was bigger than all of us, and I think everyone was surprised by just how big it became. It started off as just a colour version of the ZX81 with sound and actual pixel graphics, but it ended up being so much more.

Lawson: I was happy to have played a small part, even if I was the person who made the mistake that rendered a whole load of 48Kb games incompatible with Plus 2A/Plus 3 – oops. I still like to impress people by being able to say that not only have I flown a Spitfire but perhaps my second greatest achievement was being involved in writing part of the firmware for one of the most iconic home computers ever made.

Goodwins: Personally I can't believe I was so lucky as to get to work at Sinclair Research. Teachers had told me off for years for neglecting my studies because I was hooked on the ZX81 and then the Spectrum, and indeed I mucked up my A levels. But suddenly all the stuff I'd obsessively inhaled had got me into the company that was seen as one of the most aspirational in the country at the time. That's heady stuff when you're 19. But that's nothing compared to what I learned there from the people, who were the brightest, strangest and best lot I've ever worked with. To be involved in new technology before it was public, to see new computers come to life, to have fierce arguments about what, where, when and why, and to be in a place where everything was about the future and nothing was out of bounds – and was also deeply dysfunctional – was such an amazing start to my working life. And at the centre of it all was that little polychrome box with its own quirky, smart, future-facing and, yes, dysfunctional, personality.

Grant: Yes, it makes it worthwhile and it's nice to still be getting the occasional fan mail.

Thank you to all of the contributors and to Colin Woodcock for supplying photography.