The story behind Marvel Snap's strangest card

WHAT?!

I've been playing Marvel Snap for months now, and there's a particular card that has been blowing my mind a bit. Agatha Harkness takes over your hand and plays your cards for you. She essentially turns the game into an auto-battler. And since I first encountered her, I've been trying to work out how she goes about all this, and why she's in the game in the first place. [Unsurprising spoiler: my theories were deeply incorrect.]

Rather than go online and Google the answers, I spoke to Ben Brode, the co-founder and chief development officer at Second Dinner, the creator of Marvel Snap, and the former game director of Hearthstone. Everything he told me was fascinating, so this is quite a long interview. And even if you already know how Agatha works, I do think it's worth reading what Brode has to say about the design and all the other points we touched upon.

Also: super quickly, Marvel Snap is that rare game that I think makes players feel a bit like game designers themselves. As players create decks and synergies, they're really starting to reprogram how they want the rules of the game to work for them. Speaking to Brode I was struck again and again by the sheer love for the minutiae of design that came through in everything he said.

Also also! This piece contains major spoilers for the TV series Wandavision. You have been warned.

Firstly, I saw your GDC talk this year about the development of Marvel Snap and it was fascinating. My colleague was at GDC this year and he said it was a great conference, but it also felt quite unsettling because AI was the big subject - the kind of big opportunity and fear that everyone was talking about. There were a lot of talks about what AI can do and a lot of people being afraid of what AI will do to their jobs.

And then I watched your talk and found it very moving, because you're talking about what feels like a very human process of making a game through hundreds of canny little decisions and revisions, right down to thinking about the nature of luck and how players experience and perceive luck. It was a wonderful talk and, even if this wasn't intended, it was fascinating to look at in the light of the AI discussions.

Ben Brode: I'm really glad to hear that. You know, it's interesting, the way that these AIs are trained anyway, is they're trained on human knowledge. And we're not done having new thoughts... You need someone to think outside the box, right? You need people for that I think.

I wanted to talk to you about a specific Marvel Snap card today, but before that I wondered: can you talk to me general about the process of designing a card? Because I was trying to sit here before we got on the call and I was thinking, does the process always start the same way? Or does it start many different ways? I'm wondering, maybe you have an idea based on a Marvel character, or maybe you have an idea based on a cool thing a card could do, and you're sort of fitting it together from there?

Ben Brode: Sure. And you're right, it's multi-directional. So in card games, we often call the two directions top-down and bottom-up. And traditionally with card games the name and the art is at the top of the card and the card text is at the bottom of the card. So top-down design you start with the name and art: 'Okay, this is going to be a Captain America card. What should he do', right? And then bottom-up design will be like: 'Okay, we have a lot of cards that have downsides. It'd be fun if you can make a deck where you could get rid of the downside somehow. So let's take a card that removes the context of the next card you play.' Now, who could do that? What kind of Marvel characters have power nullification abilities? I'm gonna go through the encyclopaedia and the wikis and try to find somebody who kind of matches that thing and then slide them all together.

So we do both things. They have pros and cons. Going bottom-up, you get designs that could really help bring new deck archetypes into play. Key role-players. Like, we need a card that moves a card if we're going to have cards like by Multiple Man, right? You have to have stuff that does this. So, maybe Iron Fist could punch him to the left or something. I don't know. So you come up with the thing you want to do first, and then you put the best fit flavour on top of that.

But going top-down really expands your brain. As in, what would a cloning person do in this game? What would Mirage, who causes hallucinations, do? What would she do in this game? Or what would Mysterio do? Thinking like that, you're not thinking about mechanics, you're thinking about delivering on a fantasy and some of the craziest designs come from that.

Is there a world in which sometimes you have three or four potential ways you could take one character? So, I'm picking Squirrel Girl for this example, just because she popped up in a match the other day. Was there a point at which maybe there were three or four competing Squirrel Girl designs? I can already tell that's a bad example.

Ben Brode: Oh, yeah, certainly, certainly. So we often start out just spitballing. So, for example, Colossus, right. What is the fantasy of Colossus? What is it about him that makes him, like, uniquely him? I think it's that he can't be hurt in any way, he transforms, and so he's got a form that can be hurt, but then he can become unhurtable? Maybe it's the fact that he throws Wolverine at somebody? That's a core fantasy of Colossus. And which of those fantasies do we want to explore? Because all of them, I think, are pretty iconic.

And so we'll just like write designs for all of them. And see if any of them stick. Sometimes they have multiple ones that stick, and we've got to choose one. And then we save the other ones for other future cards. And sometimes we go with one and we try... For example, our initial Debris designs? When you played her, she used wind powers to blast everybody else away from that location. But we didn't like having this kind of mass move affecting the game so much, so we started toning it back. Eventually, we needed a new design for her. And so, okay, well, let's go back to the list of crazy ideas we had, and think a little bit differently. And so now she creates debris across the board instead.

One of the interesting things from your GDC talk comes in here, I wonder? You mentioned a comment from George Fan, the creator of Plants vs Zombies, who said that when it comes to in-game instructional text, eight words is really about as far as you can go with things - people won't read more than that reliably. I thought that was a brilliant observation. But when you put it into action, when you talk about minimising text complexity, I started to wonder: do you ever get an idea for a card which is so cool, but it's just inherently complicated? I'm thinking about, do you ever have, like, the Thomas Pynchon equivalent of a card where the joys are really joyous, but the barrier to entry to even understanding how it works is so high, you just can't go with it? Does that ever happen?

Ben Brode: Yes. All the time. Constantly, that's a constant thing that we have. But the thing is, we can almost always get there, okay? It just takes a lot of work. So in card game parlance, we have this thing called templating. Because if you're going to have two cards that do similar stuff, they should have the same template? So how do you say 'destroy a card'? Let's just have that be the way that we say it and then every card that destroys a card, we always say it the same way? So that's the template.

So we have templating meetings where we get in and we say, 'Look, this is how we're thinking about saying this.' And everyone's like, 'Well, that is just completely not understandable.' Or they say, 'It's way longer than the other cards in the game.' How do we use our wordsmithing to, you know, try and get it simpler, get it smaller. What's the essence? What really matters? Maybe this card is doing two things, can they just do the one thing?

There's ways to cheat, also! For example, Storm creates a location that has its own text that turns into another location that has its own text. Snowguard has three cards. Well, that's a lot more text than most cards, but it's kind of spread in a way that they're all individually understandable.

It sounds almost like you have moments where you're suddenly realising, 'Oh no, I'm actually a writer by this point.' Because those are writerly problems? Contraction and clarity. I really struggle with that every day. This isn't really a question for anyone other than me, just being a writing nerd. But it's really interesting to see a point where a discipline I kind of understand overlaps with other disciplines. Suddenly I realise: 'Oh, you're experiencing the same glorious hell that I experience every day.'

Ben Brode: So there's a talk I've never given publicly, but I gave it at Blizzard before I left, which is about the language of video games. And how just critical it is writing tooltips, writing dialogue boxes, writing the buttons that you put on dialogue boxes. If you put out a big dialogue box and the buttons are 'Okay' and 'Cancel', then you, the player, have to read the box. And if you have more than eight words in the box, you're not going to read it. People just smash one of the buttons and are like, 'Wait, what happened?' But if the buttons are 'Swap them' and 'Keep it as is' you're suddenly thinking, 'Oh, I don't have to read the dialogue box. This is a dialogue box confirming the swap, and I know this, and I'll hit 'Swap''.

In Heroes of the Storm there was a thing where they gave you a reward and to confirm it, the button just said 'SWEET!' They told you how to feel about the event. It wasn't just, you know, 'Okay'. It had some flavour and some emotion behind it. In every word we use, everywhere from changing, 'You lose' to 'Escaped', changing 'Concede' to 'Retreat', every one of these choices has an impact on the player experience. And so I think it's part of game design. It's writing, but it's part of what's important about game design too: we control the player experience, how players feel. And words are the frontline defence. That's the thing that players experience most.

This is wonderful to hear. There's so much I want to ask you about that, but I won't or we'll be here forever.

Right. I wanted to talk to you about a specific card, Agatha Harkness. I'm not knowledgeable about Marvel, even though I play Marvel Snap. I've been really gripped by this game. And I've been talking to people about this card, Agatha Harkness, and saying, 'Oh, there's this character called Agatha Harkness and her card is really wild.' And they're all like, 'Oh, no, she's really quite famous. She's been doing this TV show now and everybody knows about her.' But I was so fascinated get this card, not because of the character but because what the card did sounded so strange. I don't think I've ever seen another card like her in a game ever.

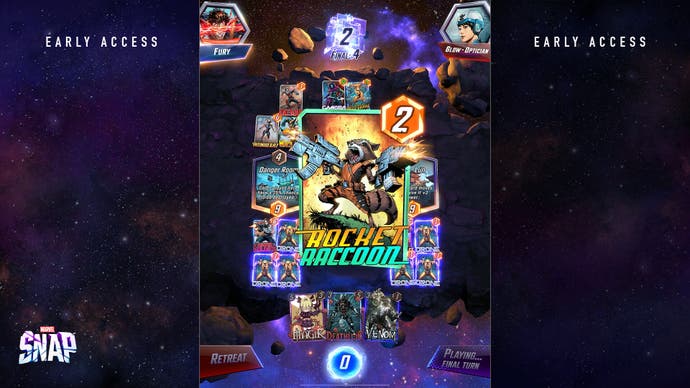

Just to clarify this for readers, if you have Agatha in your deck, she will appear in your first hand and then she will play every card for you in the game. She's six mana, so she plays herself in turn six. She just takes over your game and makes all the plays! First off, I wondered: when you're making a card like this, do you know it's a bit special from the start?

Ben Brode: Yes. 100 percent. So this is important, when making collectible card games, if people are coming to your game and going, 'Oh, yeah, I've seen this before', or, 'This is not exciting and new and different?' You need something that blows their mind and makes them think: 'Hold on! Anything could happen in this game! I don't know what to expect! What else do these cards do? I have to see all of these cards now! This is wild!'

I think one of the ways to do that most is by using design, like highlighting what's unique about your design space, right? So the design space is basically every possible card that could exist in your game. You're never going to get every possible card. But that's that's the space you have to play in. And for collectible card games, you need something unique. And it's great if people who don't even know how to play the game, if they can see those cards and go, 'I understand exactly what that does! I don't know how to win, I don't know how to play, but this card takes over and makes your plays for you? I get that!' That just requires no game knowledge. And that can be one of those things that captures people and makes them think, 'Oh, this game has got something special about it. I gotta check this out.'

Once you knew what you wanted Agatha to do, how does she do it? It's strange - I know you have bots in the game, but I never think of Agatha as just a bot. She feels different. Is she different?

Ben Brode: Here's how she works. She always tries to play herself. So if she can play herself, she'll play herself. Most times she can't, because you don't have six mana, but she always tries to play herself first each turn.

If she can't, she plays completely randomly.

[Long pause.] She what? I'm not ready. I'm not prepared for this. This is the most shocking thing I've ever been told. She plays randomly?

Ben Brode: Completely randomly. She will take a random card, play it to a random location and do it again and do it again until she's out of mana. That's it.

One of my questions later on, which I now don't have to ask, is that, sometimes when Agatha does certain things, I feel like I'm reading something into her design which is maybe not there. You know, I read all these stories about how people are fooled by chatbots and how there's a Google researcher who thinks that his chatbot became sentient. And I'm always like, 'Oh, how could you be so stupid?' But then I put the Guardian down and I'm reading quite deep things into Agatha, and you're telling me none of it is real? So one of my theories has been that there's a quirk with her because she doesn't know how to play Medusa, who only makes sense if you play her in the middle location. Agatha plays Medusa all over the place. But it turns out I'm reading absolutely everything into that? Was that the plan from the word go? Complete randomness?

Ben Brode: I mean, I think the goal of the card is not to give you a path to Infinite. I would rather you don't play Agatha, actually. I'd rather you be making hard decisions and try and puzzle out the right play. But we want there to be this really unique thing in the game. And so having Agatha be somewhat, somewhere below the midpoint line works. I want a really fun experience. I want to do something different. Yeah. Well, how do you build a deck that takes advantage of her? [Laughs] Probably don't put Medusa in it!

I was actually afraid to tell you that I have even used Medusa recently. I was thinking I should probably pick another example and lie about it all. I've just grown attached to that card for some reason. But this brings me on to something, actually. As you've said when you create this card, you know it's unique. It feels like it's going to be controversial, just because of what it does. Did you have a sense of what people might make of it? And did that turn out to be correct?

Ben Brode: Yes, sort of, I will say this. The development process here? We were terrified for years of this card, okay? Because, you know, it's like legal botting? And botting causes problems for card games. But we also knew that people would maybe bot our game whether Agatha existed or not? So if our game broke when people botted it, I would rather know about that and solve those problems in advance. And the existence of Agatha made it not something we can sweep under the rug and just forget about. 'Hey, guys, Agatha exists! We have to tune our system so that people who are playing eight hours of Agatha a day don't break the game.' That's an important thing. So she actually helped us keep in mind ways that our game could be broken, and design systems in ways that they were kind of Agatha-slash-botting resistant.

The randomness has still blown my mind. I'm going to have a glass of whiskey and stare out the window like Rick in Casablanca all night because of this. But I'm interested: even internally, when you know that Agatha is random, do you still have those moments where people on the team are almost tricked by her?

Ben Brode: 100 percent. Anytime you have any amount of pure randomness, people believe it is not random. Right? It's just how humans perceive randomness. Just you know, 'Hey, I got heads five times in a row, the coins broken!' Like, no! No. This is how randomness works. It's a bell curve of distributions right?

I should say, it's almost always a mistake to have pure randomness. Because it doesn't actually match our expectations of what a random system should do. In this case, it's fine because with Agatha, every point in the random curve is okay for us. We don't mind that she has done some really dumb stuff and some really brilliant stuff sometimes. It's just gonna happen randomly.

How do you want people to feel when they lose to someone playing Agatha? Because when the final turn comes and you've lost and your enemy has just dropped Agatha onto the board, that was already a wonderfully dark moment for me, even before I knew she was random. Dark, frustrating, but also kind of magical?

Ben Brode: Ah! This is why the card is Agatha Harkness in the first place. So this card was not Agatha to begin with. It was Adam Warlock once upon a time. It was a bottom-up design. I wanted to explore this design space. But then Wandavision came out. And there's a moment - this is a spoiler, I'm sorry. But there's a moment in Wandavision, where there's a character who suddenly reveals that she was the bad guy all along. It's Agatha and she has a theme song that plays. The theme song is incredibly catchy. It's called, 'It was Agatha all Along' [He sings it for a moment.] Like super, super catchy.

This became a very viral moment. Everybody loves the Agatha theme song. It was an incredible moment in this really, really good TV show. As soon as that episode aired, we said, 'Wouldn't it be amazing if this card was Agatha Harkness? And when, like, the whole game, you're probably like, 'What the fuck are they doing? Why would they play Medusa? To the left side? What is happening?' And then on turn six Agatha comes down, you're like, 'Oh! IT WAS AGATHA ALL ALONG!''

It perfectly matches that moment. That's what I want. That's what I want players to experiences.

Last thing. I like decks where things are slightly out of my hands. I like, morph, for example, I use them just because I like the fact that I don't know what I'm playing before they transform. So when I got Agatha, I played her for, honestly, a number of months. Non stop. And that was all I did in the game. And halfway through that, I suddenly realised, I'm probably not meant to be doing this? I'm meant to be moving on and doing other things. So I wondered: how long should I have played Agatha? How long do you want people to play her before they get on with their lives?

Ben Brode: This is one of the great joys of collectible card games, in that you can play it however you want. Do you want to play a more controlling strategy? Do you want to have a deck of high rolls sometimes and just win out of nowhere, nothing your opponent can do about it? Do you want a deck where you have lots of decisions? Lots of counterplay and you don't like losing so you put in Shang-Chi and Enchantress and Cosmo and just handle your opponents to make sure that you can get your strategy. There's like many ways to play and so however you want to do it, like the game supports, and you can do what you want.

As for moving on eventually, I think like this is true of basically any deck right? Whether it's Agatha or Silver Surfer or Onslaught, people are going to enjoy a deck and play it for a while. And I hope that at some point, we can inspire everybody to try another deck and try another deck and try something else after that. I think eventually people have had a lot of the fun, and while it's always the fun, the fun trends down down over time if you're not learning as much with that deck and you're not having new experiences. Agatha does provide a lot of new experiences for a long time. But eventually people want to go off and discover new fun.