The story of Exile, one of the greatest sci-fi games of the 1980s

Consider Phoebus.

Hello! Welcome back to the last entry in Captain's Log, a mini-series on the things we love about space - and how video games so brilliantly engage with it. You can read all of our pieces in the series in one place as they go live, here at the Captain's Log archive. Enjoy!

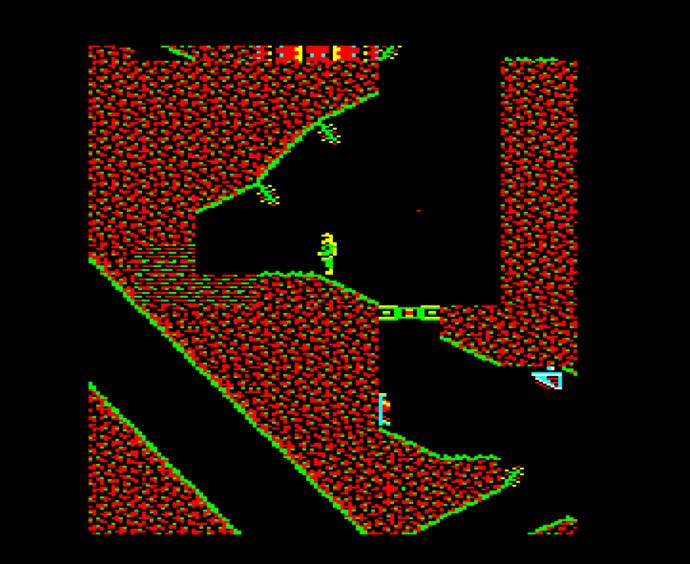

I didn't know what a Metroidvania game was when I played Exile in the eighties - probably because the term didn't exist yet. I also didn't appreciate how pioneering this BBC Micro game was. Realistic gravity and inertia; a procedurally-generated map; non-linear gameplay; advanced AI, and a coherent world to explore - this game had the lot, and bags of atmosphere, too. "We knew and intended to create something novel," says one-half of the creative team behind the Superior Software game, Peter Irvin. "But didn't know how much anyone else would like it. We wanted to play it ourselves, and it was always fun play-testing - a good sign." While the story of Exile ended in tragedy in 1992, it remains one of the eighties' greatest and most innovative games.

By 1988, the 8-bit market was beginning to shrink. Arcade conversions and budget games dominated, and original products were becoming rare. "It was still a reasonably strong market," says Superior Software boss Richard Hanson, "but it was starting to show some signs that it may have passed its peak." This failed to deter Irvin and his colleague, Jeremy Smith.

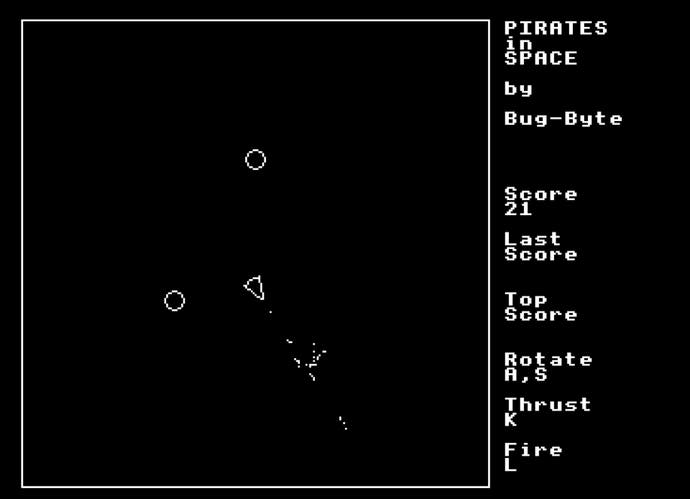

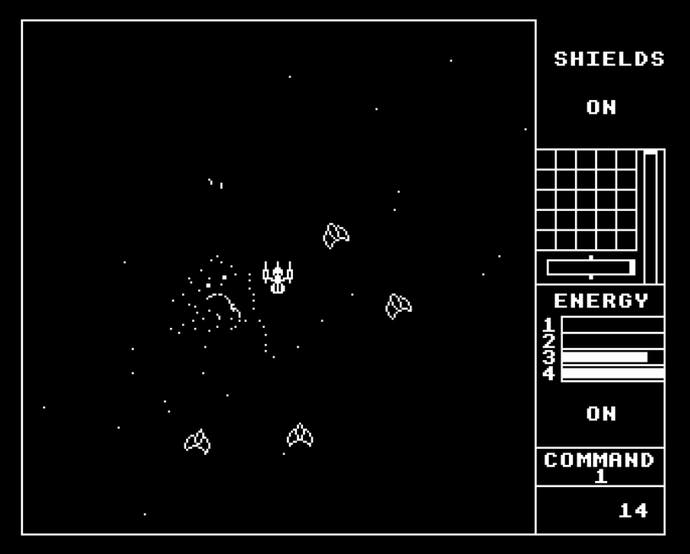

Irvin and Smith were old school friends from St Albans. Says Irvin: "There was a group of us who were excited by the home computers that were starting to appear. Ian Bell [co-author of the legendary space trading game, Elite] was a friend, too." Their school purchased a handful of Tandy TRS80 computers, and by the time Irvin and his friends were in Sixth Form, the BBC Micro had arrived. "In my gap year, I developed a game called Starship Command - while Jeremy did Pirates In Space. After university, we decided to carry on with games development."

Published in 1982 and 1983, Pirates In Space and Starship Command are aesthetically similar, evoking the Atari classic, Asteroids. Once he returned from university, Smith chose another arcade game as inspiration for his next effort. Published by Superior for the BBC Micro and Firebird for the other 8-bit computers, the Gravitar-inspired Thrust was a big hit. Irvin abandoned work on his own game, Wizard's Walk, and the two self-taught programmers finally joined forces.

Having cut their teeth on space adventures, Irvin and Smith settled on a game based around a lone astronaut. "Initially, it was just finding out what was fun to play," says Irvin. "And what was possible on the BBC in terms of speed, graphics and RAM. The game evolved as we became more experienced in building up technologies and creative ideas. Later, we created the story that fit what we could do."

In Exile, the player is Mike Finn, an elite soldier of the Columbus Force in the 22nd century. While returning from another mission, Finn must investigate the planet Phoebus. The crew of the starship Pericles, captained by Commander David Sprake, has met a gruesome fate at the hands of Triax, the slightly-unhinged scientist obsessed with genetic engineering, and the exile of the title. Alone, weaponless and stranded on the planet, Finn delves deep into Phoebus's caverns to eliminate the dastardly Triax before he unleashes his malignant creations on the Earth as revenge for his exile.

Irvin and Smith used the latter's experience with gravity-based mechanics to develop a natural physics-based engine, with the player walking, jumping and flying around a huge map infested with robots and strange creatures - all within the standard 32K of the BBC Micro Model B. Explains Irvin, "Exile expanded in ambition, yet got increasingly squashed into the machine's limited resources as we were forced to think hard about developing better ways to recode features." For example, Exile's plot code is able to extract four-colour rectangles, each capable of being expanded and remapped to up to eight display colours and reflected on the X and Y axes. "This large selection of big terrain tiles actually overlap each other a lot in the source bitmap, saving tons of RAM."

The scale of Exile is impressive, but there's so much more to the Superior game. The game's physics engine, with object collision, friction, mass variation, wind and explosive forces all influencing movement, was innovative. Testing was paramount, as Irvin describes. "It was all carefully tweaked over time so that the various puzzles worked without loopholes. The object and terrain collision tests had to be finely tuned so they were fast and felt right. Solving problems like walking into a low ceiling corner was difficult - the objects would oscillate into the roof with each game cycle. We couldn't afford the RAM to prevent it properly." Even better is Exile's AI, with enemies reacting according to a "mood" value, influenced by inputs such as friends/enemies in line of sight, hunger, pain and time. "For instance, some imps might go up [in mood] when it sees an enemy and down if its food is eaten," notes Irvin.

The realistic physics and improved AI were all part of Irvin and Smith's drive towards an immersive adventure, also the reason why Exile eschews lives in favour of constant player reanimation. "Having lives detracts from the principle of an immersive adventure," comments Irvin. "So, we decided that the player couldn't actually die. We already had a personal teleport system, so we just had to make it so that whenever your protection suit detected low energy, you were automatically teleported back to wherever you last saved your position." When Finn's suit energy gets low, the space adventurer warps away from potentially lethal situations, allowing the player to recharge and consider their next move.

As Irvin reveals, the concept took considerable work: "We had to design the game so that salient objects or puzzles could not be permanently damaged. Nevertheless, you could still get into situations where you'd used up all your grenades or nukes and could not progress as intended." From here, if available, the player could only reload from an earlier position or restart the game. It's a minor flaw in an otherwise pioneering and extraordinarily immersive experience.

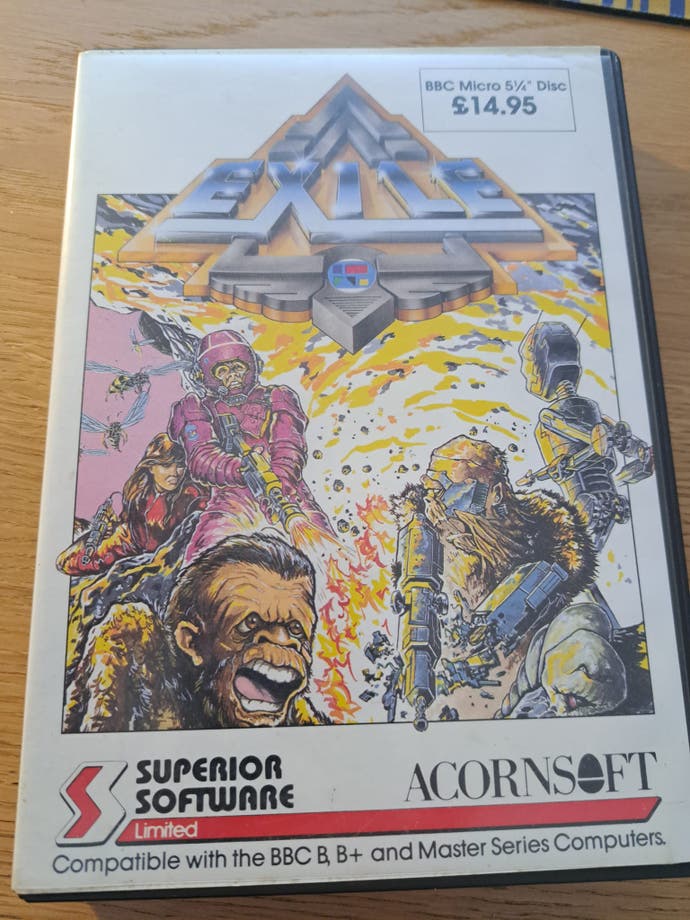

With Exile nearing completion, Irvin and Smith approached the BBC Micro's most prominent publisher, Superior Software. "I'd worked with Jeremy Smith when he produced the stylish game, Thrust," remembers Hanson. "[They] had largely completed the game - about 80-90 percent finished - when I first saw Exile. I was very impressed by its appearance and mechanics." That final thrust to completion included synthesised speech, a real treat for BBC Micro owner with enough RAM and a novella written by another friend from school, Mark Cullen. "Because the game was complex, it needed the earlier background scenario. The earlier story about what happened to the colonists was very much an interactive process with us and Mark, and he fleshed it out further."

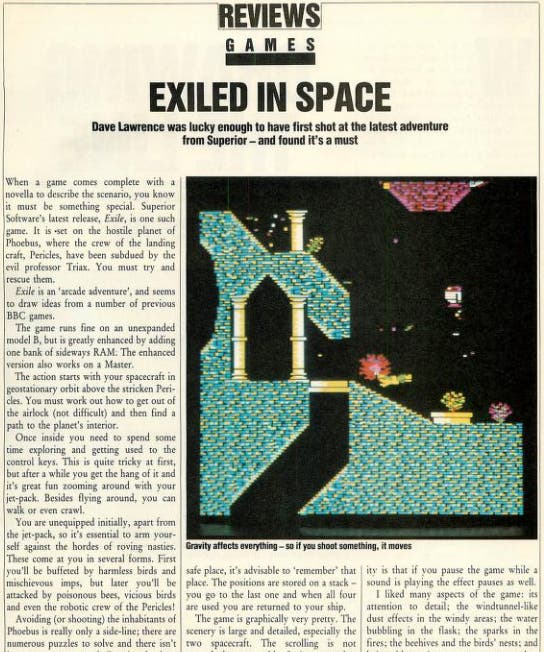

Recognising the original and groundbreaking game it had on its hands, Superior released Exile in a video cassette-sized box, incorporating the novella, instruction manual, keyboard guide and game disk. A dramatic cover, created by Superior regular Les Ives, completed the package. To everyone's relief, the reviews were uniformly good. "Exile is certainly a contender for the best Beeb arcade adventure for a long time - it's definitely the best game this year." gushed Acorn User's Dave Lawrence, and when Exile appeared on other formats, the reception was equally effusive. "The Repton games may have sold in higher quantities," notes Hanson, "but Exile performed quite well in terms of its share of the BBC Micro and Electron market. It's certainly a special game in the Superior catalogue and one of our most technically advanced."

After Exile, Peter Irvin dabbled with console development at Audiogenic and Activision. Then, in 1992, he lost his longtime friend and co-developer in a tragic accident. "Jeremy was a good friend, and it was devastating losing him. He was one of a group of us who'd known each other since school. He was bright but by nature a quietly creative person - not just technical, but also artistic and musical."

Exile was the only game the pair would collaborate on - a sad but proud legacy. "I think people did realise how much Exile stretched the boundaries of these early computers," concludes Irvin. "And I still get contacted by people today, how they remember racing home from school to play Exile, taking turns with friends and family to solve particular puzzles or even inspiring them to get into games or coding as a career due to it. That's the best reward for me."

Thanks to Peter Irvin and Richard Hanson of Superior Software for their time. Irvin hasn't completely abandoned his plans to bring Exile to Android phones. If you want to know more, keep an eye on this.