The story of Mean Machines magazine

"You have to believe that it was a special place and time".

The video game landscape in the UK at the turn of the 90s was perhaps more confused and fractured than your fading memory can recall, assuming you're old enough to have lived through it. Home computers like the ZX Spectrum, C64, Amiga and Atari ST were still the main conduits of interactive entertainment in the majority of homes up and down the country (despite the fact they were often purchased by naive parents with the intention of helping their children with their homework), and the invasion of Japanese consoles from the likes of Nintendo, Sega, NEC and SNK was yet to begun in earnest.

After years of politely tolerating fair-to-middling home computer ports of cutting-edge coin-op hits, British players were more than ready for truly dedicated gaming hardware which could accurately replicate the kind of intense gameplay seen in local amusement arcades - which is why consoles like the PC Engine and Sega Mega Drive made such a massive impact when they began appearing on the shelves of independent importers towards the end of the 1980s. It was the beginning of a period of console dominance which persists to this very day, and in the United Kingdom there was one magazine which stood at the vanguard of this gaming revolution: Mean Machines.

Mean Machines' origins can be traced back to two separate publications from rival publishers: Newsfield's Zzap!64 and EMAP's Computer & Video Games. The former - headquartered in the historic market town of Ludlow and focused on the Commodore 64 home computer - would present a teenage Julian Rignall with his first serious education in games journalism, and along with sibling publication Crash challenged the established order by elevating its writers to the status of celebrities. Each staffer had their own set of illustrations courtesy of in-house artist Oliver Frey and were permitted to gleefully stamp their personalities over each and every piece of content they produced, ultimately forging an intimate connection with the reader that in turn generated a legion of loyal fans. Perhaps most importantly of all, Newsfield employed genuine gamers straight out of school. Rignall was a case in point; prior to joining Newsfield and Zzap!64, his biggest claim to fame was becoming the UK Video Arcade Game champion in 1983 - an award bestowed by CVG itself.

Newsfield's pokey Ludlow office was the perfect hotbed for a revolution in the way in which the specialist media covered video games, but this love affair couldn't last forever. "After putting our hearts and souls into Zzap!64 for several years, Steve Jarratt and I got fed up with Newsfield's drama and politics and left the company to work together as a freelance team," Rignall explains. "We secured a retainer with EMAP and produced articles for CVG and Commodore User for several months. At that point, Eugene Lacey - then-editor of CVG - tried to get me to join the magazine as a full-time member of the editorial team, and although I initially said no, he eventually made me an offer I couldn't refuse. It was a really, really tough decision, and Steve was understandably livid at me for breaking our partnership, but I joined CVG as Deputy Editor in the autumn of 1988." On a side note, if the name Steve Jarratt seems familiar, it's because he went on to be the launch editor of Total!, Edge and Official Nintendo Magazine at Future Publishing.

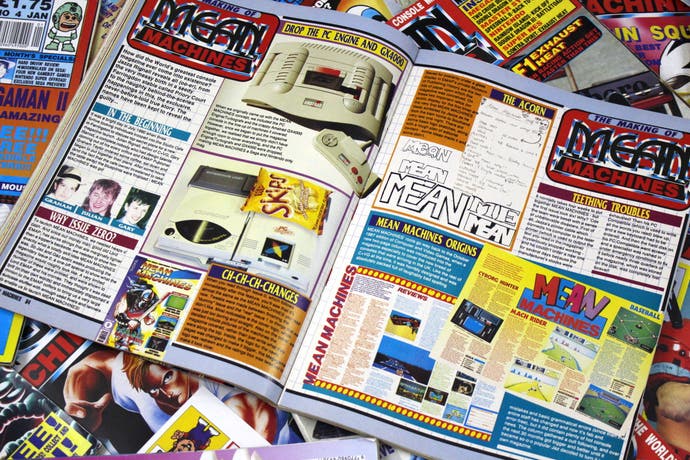

The publication Rignall joined was the UK's leading multi-format games mag, but it was undergoing seismic change which reflected the turmoil of the global gaming industry. After covering home computers for the best part of a decade, CVG was slowly but surely turning its attention to the new wave of Japanese console hardware which was arriving on British shores. The Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Master System were the first to find fame, but these 8-bit platforms were about to be superseded by a new generation of powerful 16-bit challengers. To accommodate these new pieces of hardware the decision was made to give them their own section at the back of the magazine. "The very first Mean Machines column was published in the October 1987 issue," explains Rignall. "It was originally written by freelancer Tony Takoushi and covered console and import games - which was quite forward-thinking for its time. I ended up taking over the column in early 1989 after I'd been at CVG for a few months. At that point the console market was really beginning to kick off, and I was extremely excited about the Mega Drive and the PC Engine - both were manna from gaming heaven as far as I was concerned."

But a few pages at the back of a magazine which was still primarily focused on home computers was never going to be enough to contain this explosion of thoroughbred gaming goodness, and Rignall cannily sensed that the time was right for a publication which could lavish its full attention to these thrilling new systems. "I pitched CVG publisher Graham Taylor the idea of potentially spinning off Mean Machines as a solo publication multiple times during the spring and summer of 1990. He kept on saying no, but I eventually wore him down like water on stone. There were signs everywhere that it could work - the import market was booming, the Mean Machines column was getting tons of its own mail so reader interest was obviously very high, we'd produced several 'Complete Guide to Consoles' magazines that had sold well, and ultimately there was a huge gap in the market. Few, if any magazines were really covering consoles, and to me they were the most exciting aspect of gaming - a market that was just waiting to explode. I remember talking to Graham about it one afternoon during the height of summer, and he finally said okay, and gave me the budget to produce a dummy magazine - the legendary 'Issue Zero'. That focus-tested well, and we launched the magazine proper in October of 1990."

To begin with, the core Mean Machines team consisted of Rignall and fellow staff writer Matt Regan, with Gary Harrod and Oz Browne on art and design duties. Richard Leadbetter - whose name (and indeed, face) will be instantly familiar to those of you who keenly follow Digital Foundry's coverage on this very site - would join the ranks later, while fellow CVG staffer Paul Glancey, another former Zzap!64 and Newsfield veteran, contributed reviews as the workload grew. The dawn of the new decade saw the NES and Master System duking it out for dominance of the living room while the Nintendo Game Boy created a new awareness for the potential of portable gaming; all three would feature in Mean Machines. Virgin Mastertronic was about to launch Sega's 16-bit Mega Drive officially in the UK, making it another obvious inclusion for coverage in the mag. However, despite the fact that Rignall and the rest of the CVG team had passionately championed the import-only PC Engine and had included it in the aforementioned Issue Zero, that particular pint-sized console didn't make the final cut. In a decision which is easy to criticise with the benefit of hindsight, the recently-released Amstrad GX4000 took its place.

"The GX4000 was, how can I put it politely... unfortunate," says Leadbetter. "Ultimately, I think it quickly became clear that it was simply not worth our attention." Rignall reveals that the inclusion of Alan Sugar's latest disasterpiece was largely to do with more mundane matters; as a console which was officially available in the UK, it had the potential to draw in advertising revenue, whereas the PC Engine was still only available on import. "The GX4000 was a publisher thing - Graham wanted it on the cover because he felt that it might lure in a few advertisers. Once it was clear that it was a complete and utter failure, it was replaced with the infinitely more exciting Super Famicom, which of course became the SNES in the west. The Neo Geo was considered for inclusion but in the end we felt that it was a little too niche to be emblazoned on the front of the mag, despite being very cool."

The timing of the first issue of Mean Machines was fortuitous to say the least. Despite being a distant second to Sega in the UK market, Nintendo was gaining traction thanks to the fact that it produced the only home console with a Teenage Mutant Ninja (or Hero, if you prefer) Turtles game, and that was wisely selected as the basis for the debut issue's cover image, with in-house artist Harrod creating an entirely bespoke piece of artwork. Harrod - these days employed as Creative Manager at Square Enix Europe - would fill a role similar to that of Newsfield's Oliver Frey; his art imbued the publication with its own unique identity.

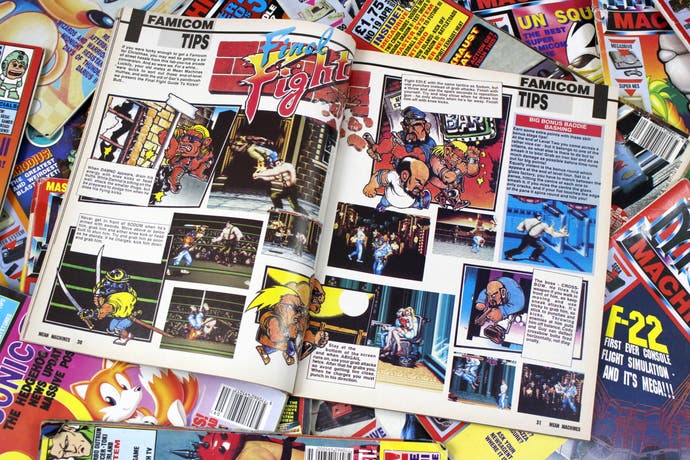

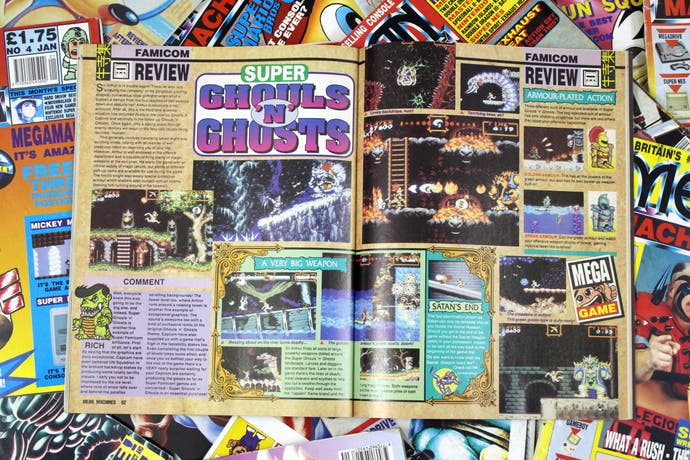

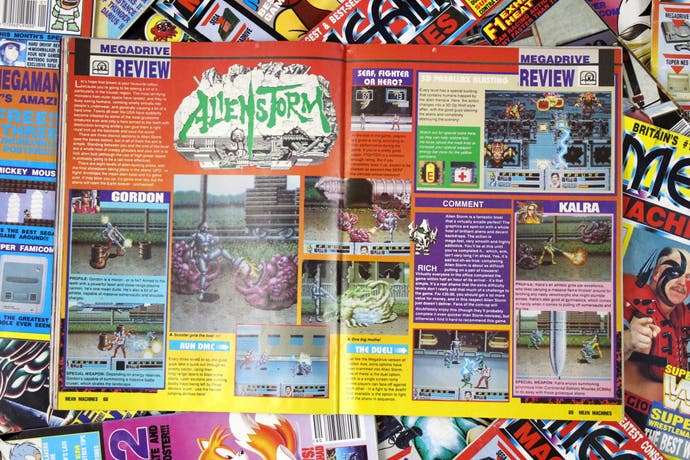

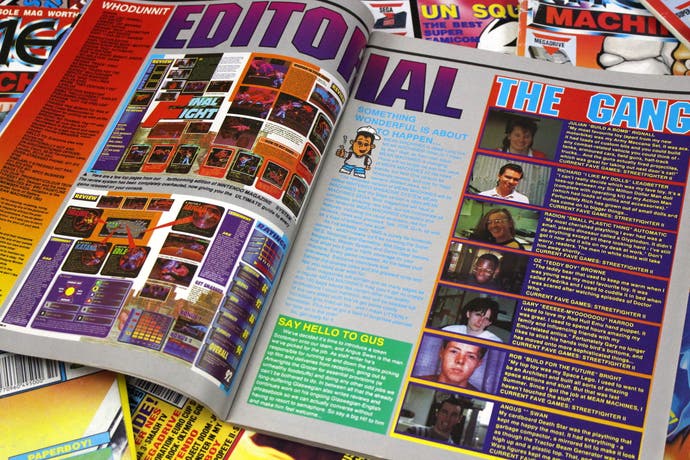

"I think Gary's work was hugely important in establishing Mean Machines' visual style," says Rignall. "He was heavily influenced by manga, and that Japanese art style worked perfectly with all the import games we were covering at the time. To me, the most iconic part of the magazine were the little illustrations of us that we used for the reviews. They really gave Mean Machines a unique look that no other British magazine had at the time. The other thing to consider is that we worked very hard to break Mean Machines' content up into bite-sized chunks. We didn't want massive walls of text, and instead went the opposite route, breaking down reviews into a series of extended captions and box-outs, with plenty of pictures and information. That gave Mean Machines a very busy, dynamic look, and made the magazine feel like there was a ton of content on each page."

In the days before the internet, physical mail was the most obvious way for readers to ask questions, supply feedback and generally connect with the people who produced the magazine, and the Mean Machines team actively encouraged this process from the very start. "We wanted Mean Machines to be as interactive as possible, so that it felt like a community of gamers," adds Rignall. "That's why we went to such lengths to make sure that there were always a myriad of ways to contribute to the magazine as a reader. We'd try to make competitions creatively entertaining, and asked people to send in all sorts of stuff, from pics of crashed cars to bizarre photos of themselves and their pets. I think it helped make the magazine feel down to earth, irreverent, and funny - we absolutely didn't want to be a publication that kept everyone at arm's length and spoke down from on high." It worked. "There was literally a new big grey sack of mail arriving every day which someone - me, specifically - would have to sort out," says Leadbetter.

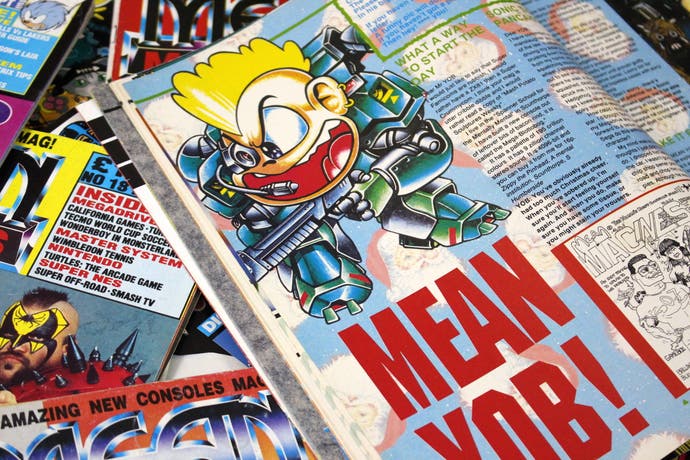

The letters page was overseen by the fictional Mean Yob, who quickly became the magazine's mascot. This section of the magazine saw insults being dished out with side-splitting regularity, but who on the team was responsible for these witty ripostes? "That would be me!" chuckles Rignall. "I actually started answering the letters in CVG under the Yob pseudonym to spice up what was otherwise a pretty humdrum page. I then took that character over to Mean Machines and amped up the manic rhetoric by several degrees. I tried to find a balance between being funny, while not being overtly mean - which I didn't always get right - but I do think it was a pretty amusing read for the most part, even if I say so myself. I basically just riffed on what the readers were sending in. If they were being silly, combative, or asking stupid questions, I'd respond in kind, but if they were serious, I'd try to come up with a sensible answer."

The capacity for causing offence was obvious, but readers saw it as a badge of honour to be insulted by Mean Yob, as did the staff themselves. "Let's not forget that Jaz upped the ante there by specifically asking readers to send in photos of themselves so that he could insult them," points out Leadbetter. "Good old 'Insult Corner' - I still can't believe people sent in pics," Rignall adds. "Although I have a sneaking suspicion that what they were actually doing is sending in pictures of their friends. Either way, it was highly entertaining, and readers seemed to love it. I can't believe some of the jokes and double entendres - and indeed single entendres - we used to write, but for the most part we got away with it. We'd occasionally get complaints from parents, but fortunately they were rare, and we always just laughed about it. Mean Machines was basically a reflection of how we all talked and joked with one another - a natural editorial style that evolved out of our general office interactions and banter."

Connecting with the readers in this fashion often had unexpected benefits. When an intriguing fellow who shared his name with a popular brand of washing powder submitted an amusing comic strip detailing the fictional exploits of the Mean Machines team, it was printed in the magazine. "I'd been sending comic strips into Mean Machines mostly to try and get free games as I didn't have a lot of money, but also wondering if I could somehow one day make a go of cartooning," recalls Eddy Lawrence, better known to Mean Machines readers as Radion Automatic. "Then one day Jaz got in touch to say they didn't need a cartoonist, as they already had Gary Harrod, who can actually draw (fair point), but they were looking for a new staff writer, and would I be interested? Spoiler alert: I was indeed interested. I came down to London for an interview and Jaz kept me waiting for about two hours while I cacked myself, worrying there was going to be a gaming proficiency test. In the end, he asked me about two questions, warned me the money wasn't great and then offered me the job. It was amazing, and I have to say quite a leap of faith on Jaz's part. To be honest, I don't know if I've ever properly thanked Jaz for taking a chance on me. Him and Rich taught me so much, and it completely transformed my life, and led to so many other awesome experiences. As time goes on, it actually gets harder for me to believe it ever happened."

After crossing the divide between reader and staff writer, Lawrence began to appreciate what a massive impact the magazine's fanbase had on the evolution and success of Mean Machines. "The readers basically gave us permission to be ourselves. A lot of the humour in the mags came from either in-jokes in the office that were taken to increasingly illogical conclusions - such as Gary being a vagrant and Rich's 'phone box frolics' - or just us being really snarky, or losing our minds. So it was a big confidence boost to know that the readers got it, and liked it. There were a couple of other mags that you could see were trying really hard to be 'down with the kids, yeah?' It was really transparent, like having a Christian youth group do a 'special assembly' with skits about not smoking, or not denying the Holy Trinity. We never had to second-guess the readers, because they were an intrinsic part of the mag. It went both ways, of course. The first issue I worked on gave away a free plastic model of Jaz on the cover. I can't think of another magazine ever where a figurine of the editor would have been seen as an actually desirable free gift."

Perhaps the most famous example of the readers taking a throwaway Mean Machines joke and running with it is the legend of Dwayne Milton of West Wormwood. "There's not much of a story behind Dwayne unfortunately, he was just a product of my rather strange sense of humour," admits Rignall. "While compiling the masthead for Mean Machines issue one very late one night, I thought it'd be fun to spice it up by sprinkling in a few irreverent jokes. As I wrote out the competition rules, I thought it would be entertaining to have someone banned from entering them for a really arbitrary reason, and made up Dwayne Minton on the spot. That then developed into an ongoing in-joke where we'd mention him every month." Readers would write letters chronicling Dwayne's shambling exploits and he was even featured in pieces of reader artwork; a largely aimless joke concocted during the stupor of a late-night work session had been given life.

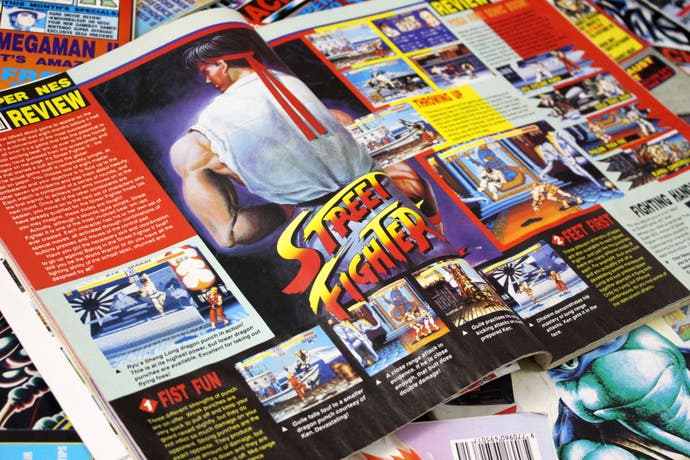

Such humour made the process of creating each issue of Mean Machines more bearable for the team. "The first week was always a comparative doss for several reasons," explains Lawrence. "Namely, you'd be in recovery from the punishing onslaught of the last press week. It was like we didn't realise that deadlines aren't like earthquakes - 'Oh, we had one of those last week, it'll never happen again'. So there'd be endless Mario Kart and Street Fighter 2 tournaments, and you'd spend a lot of time either catching up on big games from the last month that you'd missed, or really getting into playing your lead reviews for that issue. You'd also spend a lot of time just watching people play stuff, especially the big games, hoping you could get a go when the reviewer went for a wee. The next two weeks were more like having a proper job in terms of knuckling down. The last week was, without fail, a total clusterfuck. You'd get in early (or in my case, marginally less late), stay until maybe 11, and perhaps be in at the weekend as well, trying to catch up on all the stuff you should have done in the first week, and swearing that you'd definitely do that next month."

"It was a really odd way to work, but it has a tempo that you eventually get used to," adds Rignall. "Mean Machines was a complex magazine to put together, with a quite sophisticated page design that needed tons of pictures, captions, and sundry other info. That made it very labour intensive, especially for the art team, and we were always making last-second changes when we spotted mistakes and pictures in the wrong place. Most months, we used a courier to ferry the final pages to the printers at some ungodly hour of the morning so we could hit the press deadline." Lawrence also points out that the team's dedication to creating the best content possible contributed to the often fraught nature of the monthly production schedule. "The reviewing process was very time-intensive, even without doing screenshots. I'm very proud that we never wrote rush reviews. One of the major strengths of Mean Machines was definitely its critical authority. I think the readers could definitely tell that we all knew what we were on about. So every game got the attention it deserved, unless it immediately apparent that it was a shambling mockery of a parodic travesty of a farcical charade. We'd agonise about the percentages, especially once you were scoring something in the 80/90 per cents, and there would be heated rows about some games. It wasn't something we could just churn out."

Of course, being surrounded by video games on a daily basis presented its own problems when it came to workflow. "Let's not talk about the weeks we'd spend playing Super Mario Kart, or when the Street Fighter 2 arcade machine turned up," laughs Leadbetter. "Literally no work would be done." Rignall smiles at the recollection. "We used to have John Madden Football leagues, too. Everyone worked incredibly hard, but somehow we always managed to find time for plenty of gaming. For me, playing a few rounds of Street Fighter 2 really helped blow off steam when things were getting stressful." As if any more distractions were needed, there was always the threat of an unscheduled celebrity visit. "I remember Brian and Terry from East 17 doing their best 'Beavis & Butt-Head' laugh at a Take That poster Gary had stuck up behind his desk, which he'd graffitied over so it looked like they were having an orgy, complete with a bottle of champagne relabelled as 'cock lube'," recalls Lawrence. "They were in the office for a Street Fighter tournament. Their management had rung up saying they were big fans and wanted to be in the mag. I remember going to the smoking room with Brian and asking him how long he'd been reading Mean Machines, and him laughing and saying 'About five minutes'. We ended up spending most of the day sitting in the pub with them while they talked about smoking weed. They were great."

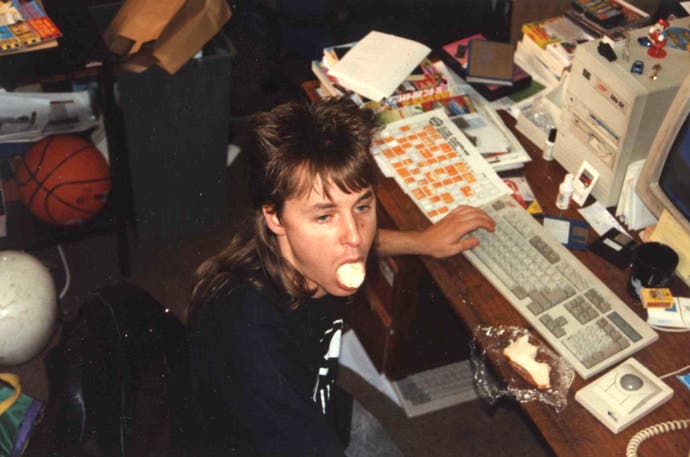

Set in the bustling heart of London, EMAP's Priory Court offices were the base for the company's magazines, including CVG and Mean Machines. The ageing building - which was a stone's throw away from Farringdon Station - holds some particularly grim memories for those who dutifully slaved within its walls. "It hadn't been decorated in years and there was no air conditioning so it stank to high heaven, particularly in the summer when certain staff members' lack of personal hygiene became brutally obvious," winces Leadbetter. "Piles of junk and magazines everywhere, no real evidence that we had cleaners of any description. Oh yeah, and actually illegal by today's standards as quite a few people smoked in the office."

"We had fruit flies around the Terence Piper vending machine, which served something called coffee," says Rochdale-born Paul Davies, who would join EMAP in 1992. "The cleaners would leave notes saying 'please keep this area clean' which I found confusing. Somebody once made an awful mess in one of the downstairs toilets, and to this day nobody knows who that was. Somebody peed on the floor of the CVG toilet. This might've been me on a deadline day when all I could see was kaleidoscope patterns." Despite the potential for health and safety violations, Rignall admits that he still has fond memories of Priory Court. "The office was pretty damn rank - especially the photography and game room. Lots of mystery stains on the carpet, and rubbish everywhere. Every so often we'd have a cleanup, but it was pretty tough keeping the office in any kind of order because we were working so hard all the time, and received bags of mail every day. Still, even though it was a bit of a pig sty, it was a great place to work, assuming you could put up with the death metal and gangsta rap that Gary Harrod endlessly played on his ghetto blaster."

Priory Court was dirty in tone, as well. "Aside from my feet, the filthiest thing about Priory Court was the minds of the people who worked there," laughs Lawrence. "That place was like the Renaissance, Left Bank and Vietnam of vulgarity, all rolled into one. It was never mean-spirited, but we just used to sit there utterly ripping the piss out of each other in the most obscene ways. Pretty much every interaction between us would have been a sackable offence in any other workplace. Jokes about fisting each others' mums were so frequent that they were ultimately reduced to a universally-recognised mother-fisting noise, that was somehow an acceptable response to pretty much any comment or question."

Despite the proliferation of worrying matriarchal insults, a keen sense of camaraderie is still felt by practically everyone who worked within the walls of EMAP at the time. "It was like college, and feels like family today," Davies adds. "Everybody was themselves, no pretensions. We had jobs to do, and it would get serious, but Jaz would always hop down the stairs two or three at a time swinging on the handrail and being super cheery, while Rich would exchange disgusting noises across the office with Gary." The common theme is that despite the insane deadline crunch and often irksome working conditions, a job at EMAP was a chance to turn your pastime into gainful employment. "We had a great team of people that really got on well, and what you read in the magazine was basically an extension of the banter and exchanges that were going on in the office," says Rignall.

"It was liking living in a zany sitcom," adds Lawrence. "I was working with my best friends, nerding out over games, pretty much writing whatever I wanted, and almost getting paid for it. It was fucking wicked. Right from the start, Mean Machines had always been quite anarchic, but it just kept evolving and improving. Jaz had always encouraged everyone to experiment with words and pictures and stuff, so as new people came on board it just got better. For me, I was surrounded by these constantly inspiring, hilarious, and passionate people, and they really made me want to raise my game. We spent pretty much all of our time together, in and out of the office - if you missed a night in the pub, it was like missing a week of normal human time. There'd be three new running jokes and a radical reappraisal of Atomic Robo Kid to catch up on. All of that fed into the mag, and really contributed to its quality."

Given that the team at EMAP was, in the early years of the magazine, working with equipment that might cause William Caxton to stifle a chuckle, it's understandable that the stress regarding the production of each issue was felt rather keenly by Rignall and his team. "We had monochrome 286 PCs, just about good enough for playing Prince of Persia and not much else - though I recall that Jaz had a colour screen and a top-end 386 for gaming," says Leadbetter. "We would type up reviews, then Jaz or Paul Glancey - who's now at Criterion as a Senior Designer and Producer - would sub the copy, then copy and paste it into a package called Ventura, which produced the 'galleys' - the text as you would see it on the page. It was then printed on a gigantic, super-expensive laser printer and given to the artists who would cut out all the text and stick it on a page, mark it up for colour and add the screenshots. We shot these using a Minolta camera, onto 120mm film. I dimly recall we'd get maybe 15 shots on a roll, then we'd pop across to a studio in Farringdon Road then get them processed. If you were lucky, you may have seen the odd naked lady."

"Taking screenshots of games is my recollection of one of my earliest staff writer tasks," says Scotsman Angus 'Gus' Swan, who joined the magazine in 1992. "It was done in the games room with the aid of a camera, tripod and ripped bit of black cloth to drape over the monitor and camera, Victorian photographer-stylee. People were continually walking in to play games and it was a bit shambolic really." Lawrence has similar memories. "The Holy Grail was what we called 'perfect pause', which is when the screen just froze when you paused the game. A blinking 'pause' sign was acceptable. Loads of games would pull up some pointless stat screen or a crappy bit of artwork, or an unnecessarily ornate 'GAME NOW PAUSED!!!' logo, and your heart would sink. Once you'd got the screenshots developed, they were filed in hand-labelled envelopes in these massive filing cabinets, which you'd have to search through any time you had to look for a screenshot of an old game. And Odin help you if Oz had labelled the envelope. He had a rather idiosyncratic attitude to checking the spellings of titles, so they could have been filed under literally any letter of any alphabet."

The process of putting together this 'cut and paste' style publication might sound painfully old-school, but it was far from being the worst example of the period. "Even though our production process seems positively Neanderthal these days, it was really advanced for its time," Rignall says. "When I started at CVG we were using typewriters, typesetters, copy editing using a red pen - basically doing everything the really old-fashioned way. Mean Machines was the first EMAP magazine to essentially be produced using computers and desktop publishing software, and even though the initial outlay for the gear was quite expensive, everything paid for itself within a couple of months. That helped make the magazine very cost-effective, which resulted in it generating a considerable profit, which Lord EMAP very much appreciated."

Lawrence keenly remembers the massive change that occurred when this new technology was introduced. "When we first got our Macs, we had people come in to train us in how to use them. When they showed us that you could do things like bold text right there on the screen, we freaked out. It was like the chimp-people and the obelisk in 2001: A Space Odyssey, except the chimp-people didn't immediately use the obelisk to sample 30 seconds of William Shatner's version of 'Mr Tambourine Man' to use as an error message." On a more serious note, Swan feels this new way of working enriched the publication, and indeed all of EMAP's other magazines. "DTP on Macs was really revolutionary at that point," he says. "EMAP was a company that really exploited the opportunity it presented for extremely slick and colourful magazine layouts. Designers went mental - particularly on double-page spreads which are this amazing canvas to present a powerful design idea."

The team allowed their love of Japanese design to heavily influence the overall look of the magazine, using publications like Famitsu as a resource for artwork and imagery. "We relied on flyers from the Consumer Electronics Show, books from The Japan Centre store and a flagrant abuse of copyright when it came to ripping off Japanese magazines, if memory serves," says Leadbetter when how Mean Machines sourced much of its official artwork and imagery. Rignall concurs. "Very occasionally we'd get official artwork for the cover of the magazine, but for the most part it was as Rich says - we plundered import magazines and books and anything else we could get our hands on. We had to be creative, because most companies just didn't have any illustrative or photographic materials to support their games. If we were lucky, we'd get a boxed copy of a game that we could cut up, but most of the time we received pre-production ROM carts that had no supporting media."

The connection with the far-east was strengthened by the magazine's intense focus on import software. "What you read in Mean Machines was very much a reflection of our personal interests," reveals Rignall. "During the late 80s and early 90s, many of the very best games were being made in Japan, and as a consequence imported games were seriously hot stuff. All I wanted to do is write about them and spread the word - once I'd played them to death, of course." Review copies were often sourced from UK-based independent importers, many of which advertised within the magazine. In these cases, the retailer who supplied the copy would be credited in the review, making it a reciprocal arrangement and thereby ensuring a steady flow of new games. "We had a number of favourite importers with great Japanese connections, and we'd regularly call them up or go visit them if they were local, and get games from them fresh off the boat," continues Rignall. "I think an endorsement from us was fairly valuable in helping them establish their credibility as a quality importer, so we never had any problems getting hold of games in exchange for a mention. The other thing to consider is that a good review from us would help them shift their games, so it made a lot of sense for them to ensure we had the latest stuff."

Mean Machines' obsession with Japanese (and to a lesser extent, North American) software did throw up some problems, however. The magazine would often cover titles many months before they were officially released in the UK, which predictably threw the best-laid marketing plans of platform holders and publishers into disarray. "Our coverage definitely caused some friction with Sega and Nintendo," admits Rignall. "They put up with it because we were generating tremendous advanced hype for their games and systems. Ultimately there was nothing either company could do about it anyway; the games and systems existed in the wild, so we covered them - and reader interest was very high."

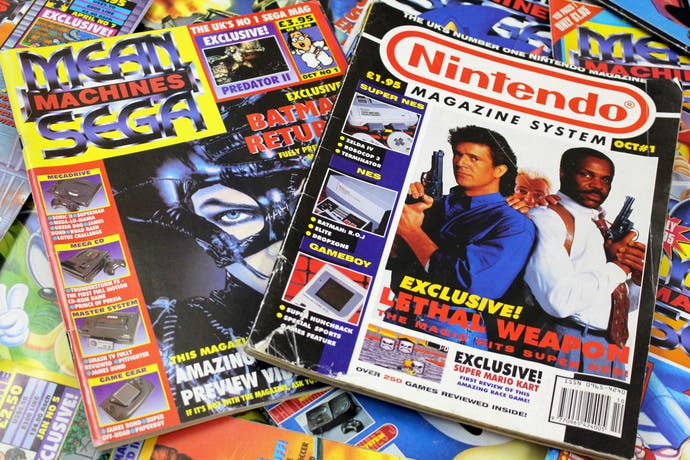

A combination of factors - the passion and talent of the team, the burgeoning popularity of games consoles and the arrival of culturally significant titles such as Sonic the Hedgehog, Street Fighter 2 and Super Mario World - bestowed Mean Machines with a fearsome commercial momentum, and within 12 months the magazine was challenging its sister publication CVG in terms of circulation. "We were actually quite conservative with our initial Mean Machines print runs - I think the first issue was only around 35,000 copies," remembers Rignall. "Fortunately it sold out, so the following month we upped the circulation by a few thousand. Even though we increased the number, demand outstripped supply, and we had a lot of people asking newsagents to reserve a copy for them - which made them order more the following month. That helped Mean Machines really grow quickly as a magazine, and by the end of the first year it was selling over 100,000 copies a month. I can't remember the exact numbers, but in its second year, Mean Machines was the biggest-selling console magazine of the period. I think the official circulation peaked at somewhere around 130,000 copies a month, just before it got split into Mean Machines Sega and Nintendo Magazine System." Purely for reference, Edge magazine sells less than 20,000 copies a month today.

After 24 issues, the decision was made to split Mean Machines down the middle. It was becoming increasingly clear that the ongoing console war was being fought almost exclusively between Sega and Nintendo, and while some lucky players owned systems made by both companies, many would simply pick a side and defend it to the death. With the SNES arriving officially on UK shores and the Sega Mega CD also hitting the market, the timing of this schism was ideal. However, behind the scenes other events were taking place which made the division even more inevitable. "Once we got the official Nintendo license, it made sense to split Mean Machines into two," explains Rignall. "I remember receiving a fair number of complaints from readers, but the bottom line is that it was a really good business decision. Both magazines sold incredibly well - Mean Machines Sega sold pretty much the same as the original Mean Machines, and the Nintendo mag went through the roof - I think the first issue sold around 170,000 copies!" Leadbetter is in agreement. "I'm pretty sure the biggest-selling issues were the first Mean Machines Sega and Nintendo Magazine System issues, because we gifted the hell out of them with the free Sega video and the Nintendo Game Boy keyring - which I strongly suspect was actually a Chinese knock-off."

It was around this time that the team switched from taking photographs of a TV screen to a more up-to-date solution - albeit one that wasn't without its own problems. "We started 'grabbing' screenshots in the worst screen capture software imaginable," says Davies. "We had to take these pics with our nose while playing the game with our hands. It would crash all the time in hot weather." Swan goes into a little more detail. "The screen-grabbing equipment was called Radius and you passed the console SCART output through it. This eliminated the need to process film and allowed you to easily manipulate images in Photoshop. I thought I'd do something wonderful and capture the entirety of Kakariko Village in The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past to be stitched together by the designer. However, the Mac crashed and I lost about 50 unsaved images and an entire afternoon's work. I cried." While pointing a camera at the screen in a darkened room might seem positively archaic by today's standards, Leadbetter feels that the relentless march of technology did have some drawbacks. "Getting dynamic images was much easier with frame-grabbers, but our concern at the time was that the images didn't really reflect the way games looked, CRT scanlines and all - something that photography did offer."

While EMAP's money men hailed the fact that its console arm was now bringing in more than twice the monthly readership, for many fans the split marked the end of the 'classic' era of Mean Machines. Both publications were arguably slicker than before and the games they covered were, if anything, even more exciting, but Rignall understands this sentiment to a degree. "Both Mean Machines Sega and Nintendo Magazine System were quality mags, but they essentially lost the irreverent, anarchic edge that the original Mean Machines had. New staff members came in and the office vibe changed somewhat, which was reflected in the way we wrote the magazines. It was like changing a band's members - things just weren't quite the same."

Entering into an official relationship with a platform holder also had an impact, of course. "I remember going to multiple meetings where we pitched Nintendo the concept of the magazine," says Rignall. "They really wanted us to do it, but we had to spend a lot of time figuring out exactly how it was going to work - the tone and style of the magazine, and the way that reviews would be done. In the end they accepted our argument that we needed complete editorial freedom; any review where we pulled our punches would destroy our credibility and cause the magazine to lose readers. That said, the general tone of NMS was a lot more mild compared to Mean Machines, and while the team did take the piss a little, it was done very carefully to make sure that we didn't say anything too untoward that might upset people. Nintendo read the magazine from cover to cover, and scrutinised every detail, so we had to be mindful about what we said."

Mean Machines Sega lacked official backing, but EMAP would eventually collaborate with the platform holder on Official Sega Magazine in early 1994; this would morph into Official Sega Saturn Magazine - which Leadbetter would edit - at the end of the follow year. "We'd had some back-and-forth with Sega about doing an official magazine for years, but they weren't really interested," Rignall says. "I think once the official Nintendo mag was established, it made sense to Sega to go that route too. We had some interesting conversations with both Nintendo and Sega about keeping the editorial teams very separate and on different floors - something that they both felt was incredibly important, for some reason. I don't quite know what they thought we were going to do, but we did make sure each team was completely independent - I was the only common link."

By the time the 32-bit era began in the middle of the '90s, things had changed at EMAP. In 1994 Rignall - the man who had championed the cause of the console and generated millions in revenue for his employer - bid farewell to Priory Court and moved into games development. "While visiting Virgin Interactive Entertainment's studios in Southern California in late 1993, I was offered a job as a design consultant - essentially playing all the games in development and offering review-style feedback to hopefully make them better," he explains. "The opportunity came along at a time when I was a bit fed up with EMAP. I really wanted to launch a new magazine to cover gaming from a higher-end perspective - it would have been similar to Edge, which came out a few months later - but it was turned down by CVG's publisher in favour of an ill-fated hi-fi and home entertainment publication that failed after only a few issues. That made my decision to leave EMAP a little easier, and I left the UK for the states in very early 1994." To make matters worse, the publisher began making some questionable calls with regards to its existing magazines in the hope that it could claim even more market share in an increasingly competitive sector. "EMAP was focused on the success of FHM and tried to roll out that success into its games magazines which were then supposed to be brands," laments Leadbetter. "At this point, management were embarrassed by the products and the people that made them millions, and went down a different route."

"The publishers started believing their own hype," Lawrence adds. "Basically, the success of the mags meant Lord EMAP started getting the attention of Grand Moff EMAP at the Imperial Court Of EMAP, and things started getting a lot more corporate. I remember one year they held a lavish Mean Machines party at the ECTS that the staff weren't allowed to attend, because they were worried we'd drink all the booze and scare off the advertisers (although, in retrospect, that was a fair assessment). Ultimately, the fatcat breadheads didn't understand the cyclical nature of the business. Once we hit about 150,000 issues a month and the team were appearing on telly, they assumed things were going to be like that forever, whereas I think the team had a bit more of a realistic understanding of things. So a couple of years later, when the consoles starting ageing and the circulation started to normalise, the management assumed we were suddenly doing something wrong, and started putting more pressure on us. The atmosphere changed for the worse."

While Nintendo Magazine System soldiered on under the somewhat snappier moniker Nintendo Magazine, Mean Machines Sega was eventually culled in 1997, judged as surplus to requirements alongside the aforementioned Official Sega Saturn magazine. The Mean Machines name lived on in the form of Mean Machines PlayStation, but it lasted just a handful of issues before the plug was unceremoniously pulled. "It was combination of factors really," says Leadbetter when asked why the final magazine to bear the Mean Machines name flopped so badly. "First of all, Mean Machines worked because it brought in raw enthusiast talent and Jaz knew how to shape that into a team. I don't really remember much about Mean Machines PlayStation but I dimly recall that EMAP tapped into existing, established staff to do it. I also think it was aimed at a 'demographic'. At this point, EMAP was starting to try to do things more professionally and lost the enthusiast and fanzine-style edge because of it."

While the brand was retired, the spirit of Mean Machines ironically lived on in CVG, which by this point was enjoying a much-deserved resurgence thanks to the efforts of Paul Davies, who had left his position as Deputy Editor at Nintendo Magazine to take the reins on what was, at the time, a fading publication. Davies steadied the ship and transformed CVG into a magazine which took inspiration from EMAP's past glories.

"Mean Machines was more than a magazine that we wanted to emulate, it was a formula built around the personalities as much as the presentation," he explains. "Tom Guise and I were devoted fans of Mean Machines, we shared the same view and were so much on the same page that we almost didn't need to spell it out for each other. And the guys we sought to bring on board fitted that profile exactly. We loved how Mean Machines took a chance on the legend that was Radion Automatic and we hired Ed Lomas for similar reasons. He was a prodigious talent in our view and also a bit crazy, which was perfect. We required that the design team got to grips with the games too, with Jaime Smith greatly contributing to the clarity of layout, while Tom Cox had a great humour to match talent. CVG became very console-oriented - we completely ditched Amiga and ST games, although we cherry-picked great PC titles, such as Quake and Half-Life. We also wanted to be as close as possible to our audience. The concept of Mean Yob was brilliant, and we wanted to share our passion on the letters pages in the same way that Jaz did in his Q&A, where he gave his opinion and boasted about things he might've seen but couldn't talk about yet. Finally, we looked up to Jaz, Rich, Gary, Rob, Rad and Oz as the way we should be as professionals, which in some cases wasn't very grown up, but in terms of getting the job done so that the magazine shone, we borrowed all of that from the Mean Machines team." Former Mean Machines art editor Oz Browne would even join the new-look CVG for a short while before moving onto Titan Books, further cementing the connection between the two.

The fortunes of CVG during this period are worthy of a feature of its own; suffice to say, the hard graft of Davies and his team paid off handsomely and attracted a loyal and committed audience, selling around 80,000 copies at its height - a striking achievement at a time when the growth of internet use was beginning to eat away at magazine circulations. During this time EMAP moved offices from Priory Court to the more swanky London Docklands, severing a huge historical connection with the hugely successful Rignall era. After a few years of success EMAP decided CVG should abandon its hardcore focus and aim for the mainstream audience to secure bigger sales. The team splintered, Davies was relegated to staff writer and Matt Howell - who had previously helmed a motorcycle magazine - was drafted in as editor. To the surprise of absolutely no one the ploy failed and CVG hemorrhaged readers, eventually dwindling to the point that it was offloaded to Dennis Publishing. Dennis later sold the brand onto Future Publishing, which turned the UK's longest-running video games magazine into a website before closing it entirely in 2015 and retiring the name. EMAP's deal with Nintendo would last until 2006 when Future won the licence and relaunched the magazine - complete with Rignall's old Newsfield accomplice Steve Jarratt at the helm - as Official Nintendo Magazine. In 2008, Bauer Media Group purchased EMAP Consumer Media and EMAP Radio for £1.14bn. What remains of EMAP's business-to-business publishing and events arm is now known as Ascential, while the EMAP name was formally retired in 2015 following the decision to move to digital-only publishing.

While there have been rumours of some kind of revival in the past, it seems that Mean Machines will forever be a part of history. "Outside of YouTube, I don't think any media outlet enjoys the same affinity with its readers as Mean Machines did at the time," says Davies. "When I joined the team, I fitted in because I knew what they liked since it was what I liked too. We were hired to contribute to a team, not to fulfil a role. Mean Machines and CVG were allowed to be run like little gangs with very little interference from the publishers." An online revival would arguably make the most sense, but Rignall - whose career has seen him hold senior roles at IGN, Future US, Walmart.com, Bank of America, GamePro and more recently Eurogamer sister site US Gamer, where he currently holds the title Editor-at-Large - feels that the sensitive nature of the internet would rob a resurrected Mean Machines of its anarchic edge. "If it was a full-on daily site with the kind of hyperbolic opinions, piss-taking, and irreverent humor that underpinned Mean Machines, it would likely cause controversy and drama these days, especially on social media. I'm sure some people would love it, but I can imagine others being offended by the jokes, or not understanding them, and fans of the games we made fun of becoming deeply upset. That said, I think Mean Machines might work as a podcast, where I think there's a little more leeway to have a bit of fun - but even then, some people might get pissed off."

While many of the staff involved have gone on to forge successful careers both inside and outside the games industry, Leadbetter feels that the Mean Machines team - and the wider stable of talent at EMAP - were somewhat exploited. "Looking back, we should have left EMAP, done our own thing and taken control of our destinies," he muses. "Instead, we ended up with fuck-all and EMAP literally coined it in. I remember a few issues into Mean Machines Sega, we'd put out a really poor cover - Fatal Fury, I think - and sold maybe 10 percent less than the preceding month. Later on, I heard the publisher mumble something about maybe only making a million quid profit that year because of it. Only!" Lawrence's regrets are a little less dramatic. "I regret trying to be cool when Chris Evans rang me when I was on 'Judge The Grudge' on The Big Breakfast, and coming across like a massive bell-end. Not starting a record label and signing MC's Nick & Steve (of "Do Me A Favour Mastermix '90 fame); those boys would have been my retirement fund. Not really paying attention to what Eddie Vedder said to me and Jaz after we saw Pearl Jam play Southend Esplanade; turns out they got quite popular after that. Sharing a bedroom wall with Gary Harrod. Camera phones not having been invented when Dexter Fletcher got thrown out of the SNES Street Fighter 2 launch - that he was hosting - at HMV."

"I regret not having a clue about career, and trusting that hard work and a true love for games would keep me in employment until I retired at 60," says Davies after a prolonged pause. "If I don't say now that I loved everybody that I worked with, even when we were bickering over nothing, I would regret that, too. You have to believe that it was a special place and time."