The two-player swing and the Shaman of Play's legacy

"I really want to see this in my playground before I go."

In Hove, there is a playground by a lagoon with an odd-looking swing. Next to the sandpit, across the way from the pirate ship but still within throwing distance of the spinning rope cage (which, by the way, reminds me of the cage Fallout's super mutants keep corpses in) is a swing designed for two.

Most weekends, my wife and I drive down to the playground to entertain and - I'll hold my hands up here - tire out our 20 month-old daughter so she goes to sleep at a reasonable time on an evening. What I love about the swing is we get to swing together, rather than me push her, and we're face to face as we do it. She's not a huge fan, I think because she prefers to do pretty much everything on her own without daddy's help, thank you very much. But when she loves it, she really loves it. And I love it when she loves it.

I don't tend to think about things particularly deeply, so I had declared this odd two-player swing awesome and that was that. It turns out, there's a very good reason why this kind of swing is so awesome - and it took a chat with a designer who is fighting for his life to understand why.

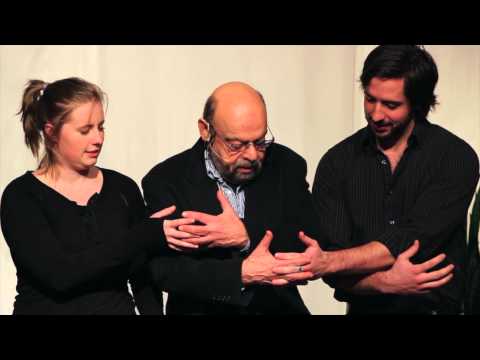

"I knew I had cancer," Bernie "Blue" De Koven, a 75-year-old designer from Irvington, Indianapolis, tells me over Skype, his tone optimistic despite the gravity of his words. "I was in stage four. It's incurable. They don't know how long I have to live. At one time I thought I wasn't going to be buried; I was going to get cremated, because I like the poetry of that, of ashes spread on something delicious and beautiful..."

De Koven is a leader in play studies, but the word "leader" probably underplays his influence on the way we think about play. He has studied and explored play in all its forms since the 1960s, and his ideas are cited by some video game developers as inspirational. De Koven wrote a book - the book - on play, called The Well Played Game. Rob Davis, designer of Insane Robots, an upcoming turn-based strategy roguelike by British independent game studio Playniac, tells me his ideas are "fundamentally important for everyone". It's no surprise to learn De Koven's nickname is the "Shaman of Play".

This spring, De Koven was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. Faced with his own mortality, he began to wonder about his legacy. That's where this two-player swing, called an Expression Swing by its creators, came into play.

"At that time I was a frequent visitor of our local playground," De Koven says. "I liked the way people were in it. You could say hello to somebody and they'd say hello back to you. If you paused to admire a dog, they would tell you it was a rescue dog they saved from imminent death. If they had a motorcycle you could say, 'hey, what a nice bike,' and they'd say, 'yeah man, thank you man.' Everybody was open. I really appreciated that. I said, 'maybe I should have something built in my playground, something I would like to see in the playground there.'

"I decided, I really wanted to see this in operation in my playground before I go."

The company behind the Expression Swing donated two for De Koven's local park, and money was raised for their installation. Thus, now sit two Expression Swings in Ellenberger Park, De Koven's legacy complete.

"I like swings a lot because I'm old and I like to sit down," De Koven says with a chuckle. "And because there's a lot of nice play that goes on around swings. There's a lot of cooperation and creative play. We have a wide variety of people, from autistic children to old people who just like to rock. But the interaction I like the most in swings is the interaction between parent and child. There's some kind of sweet, very direct connection between parent and child that goes on, as the parent tries to give the child a safe experience on a swing, yet playful and exciting and loving."

It's when De Koven gets into the nitty gritty of the design of the Expression Swing that I begin to understand why it's so great and why I love playing on it with my daughter.

"It's a major break in the whole design of swings," he says. "Instead of the parent being behind the child and not being able to connect with the child other than, 'push me again daddy! Push me! Push me!' the parent is able to look at the child's face as the child experiences glee from being driven on the swing.

"I said, man, if I had to create a metaphor for the kind of play I want to see happen in the world, this would be the metaphor. I want to see people supporting each other in play, people enjoying the experience of helping each other to play and to have fun and to experience glee. In that little Expression Swing I found everything I wanted instantiated in that design.

"The parent is looking at the child and the child is laughing and the parent starts laughing. The child is very safe so the parent doesn't have to worry about the safety. There's something very intimate about the connection. I see the same thing happening in my experience with play in games."

De Koven uses the term "coliberation" to describe the experience of playing on the swing with someone else. This is the spirit of playful interaction, the idea that each player sets the other free in joyful play.

There's a video gameness to this two-player swing, too. My daughter isn't yet two-years-old and so is too young to play video games, but that hasn't stopped me looking forward to the moment she picks up a controller and presses the start button (she already, quite annoyingly, turns on our PlayStation 4 and Xbox One by pressing the big buttons in the middle of the controllers). I can't wait to play the latest Lego game co-op with her, or teach her how to fireball in Street Fighter. But as De Koven talks more about the Expression Swing, I realise I'm already playing a game co-op with her of sorts, and that game is the swing itself.

What I want, like any overbearing father, is for my daughter to like what I liked as a child. Of course she'll love football. Of course she'll love Street Fighter. Of course she'll wear a Star Wars T-shirt. The truth is, she might not love all of these things - or any of them. But you know what she does love that I loved as a child? Swings. And this two-player swing lets me share one of my favourite childhood toys with my daughter.

"You're creating this continuity of play experience, across generations," De Koven says. "Every parent wants to give the gift of their best memories to their children, and this is exactly what happens."

Davis, like me, has enjoyed the Hove swing with his child. And he says its design has helped inform his own video game design.

"There are no rules; just sensation, movement and joy," he says. "Looking at this in game design terms, there is a refreshing simplicity in the close interrelation of the mechanical system, the resultant actions of those at play as they co-operatively shift their weight, and the emergent experience of mutual fun."

Kids - and adults - mess with the Expression Swing like modders tinker with their favourite video game. They find new ways to play with it, create their owns rules, make new and different fun. Teens, for example, stand on it precariously as they swing higher than is probably safe. Some like to pile on top of it in an attempt to work out how big the human tower can get before it collapses.

"Once, I saw a young child, must have been six or seven," De Koven remembers. "She put her doll in the seat for the infant and sat in the adult seat and started swinging. She kept on talking to the doll and saying, 'oh isn't this fun?'

"All kinds of ways emerged I hadn't anticipated, all of which gave further evidence to the value of that device as an extension of the play experience for children and for adults."

Despite his battle with cancer, De Koven still gets excited about the potential of play. He seems genuinely delighted that my daughter and me enjoy the swing in Hove, and thrilled I have come to a better understanding of it through his work. I get the impression that if he could, he'd fly all the way over to Brighton just to see us play on the swing.

He's also up for a new challenge, despite everything else that's going on in his life right now. After installing two Expression Swings in his local park, he helped design a new game that's the subject of a successful Kickstarter. This game is about legacy, "evoking what it means to pass something on to someone else". Tassos Stevens, who put the project together and spent a week with De Koven ironing out the design, tells me the game itself is a secret, but it will arrive as a parcel. The idea is a number of parcels will be unwrapped during play, with the help of De Koven and Stevens via phone.

What a brilliant idea, I think as De Koven swiftly dances onto another topic of play. Taking to De Koven about his cancer and a swing and how the two have come together is strange. I'm reminded of a lot of things, of a lot of sadness. My father died of cancer when I was 17 and I find it increasingly difficult to remember the times we played together. What troubles me most is I'm not sure whether that's because I've forgotten or we just didn't spend much time playing together.

I'm determined that, whatever happens, my daughter remembers us playing together, knows for sure I was there for her when she was a kid. For now, this two-player swing in Hove is the centre of our world. It's helping establish those memories.

And then De Koven will say something that instantly lightens my mood. "All my career, my major thrust has been to find another way to bring a new kind of play into the world," he says. "This Kickstarter was perfect because it gave me another chance. The lectures I give, every designer I advocate, every article I write, each one gives me a chance, an opportunity to take everything I learned about play and find another way to embrace it and make it happen, or make it more acceptable, or shine a light on it.

"I'm delighted!"

De Koven's legacy extends beyond those two Expression Swings in his local park half the world away. But whenever I go on the curious two-player swing in Hove, I'll be thinking of him.