The Unfinished Swan Preview: PS3's New Indie Marvel

Wonder swan.

In comedy, they say, timing is everything. And so, too, in gaming, if you're Giant Sparrow's Ian Dallas.

"Some of my most powerful experiences growing up were games and I thought I was going to go in as a writer," he says. "Coming out of college there weren't really a lot of interesting jobs as a writer in games and I figured that, five or ten years later, that might be different."

So he started writing comedy instead. "I worked in TV, which is super-fun - you're just in a room with a bunch of other guys trying to make each other laugh for 40 hours a week or often much more. But one thing led to another and I discovered programming."

The Unfinished Swan is his indie studio's first game since setting up in Santa Monica late last decade (having previously worked as a designer on The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom and Sam & Max). The timing was right, and so was the audience.

"I have no idea why they do it!" Dallas chirps with animated bemusement, discussing Sony Santa Monica's commercially risky, passionately applied strategy of nurturing local talent.

"I'm just grateful every day that the right people are in the right places so that they can make games that are not necessarily trying to appeal to the biggest audience, but that are trying to create the most interesting experiences," he adds.

Dallas's Giant Sparrow struck a similar deal with Sony to the one Thatgamecompany secured, which resulted in the fabulous trio of fl0w, Flower and Journey. Sony, very unusually amongst its giant corporate peers, loves to take a punt on weird stuff it likes the look of.

A case in point: The Unfinished Swan was very much still The Unfinished Idea when Sony snapped it up in a show of faith, bankrolling years of development.

The title, a concept video of which has been kicking around since 2008, is: "A first-person painting game set in an entirely white world," explains Dallas. It's now releasing exclusively on PSN later this year.

And what you see in that 2008 demo was effectively as much as Dallas and his team had figured out when Sony signed it. "It was essentially a mechanic and a feel," he says. "I think a lot of publishers really loved the idea, but they didn't love the idea of supporting a really unproven team.

"It took almost a year to figure out what the game was out of that. Then two years of crazy prototypes and a lot of terrible ideas."

The paint - chucked via a shoulder button or the trigger of PlayStation Move (you can play either way) - spreads across any object in its path, gradually revealing the environment as the protagonist, an orphan named Monroe, makes his way through the world.

The game begins with a sweet, storybook opening that explains the title. "Monroe's mother had always been much better at starting things than finishing them," the female narrator reveals. "When she'd gone she left behind over 300 canvasses, not one of them finished. Along with Monroe, who felt pretty unfinished himself."

Monroe's orphanage allows him to keep just one painting: he chooses The Unfinished Swan, "his mother's favourite". One day the swan disappears from the picture, leaving orange footprints that Monroe follows into a strange world.

If it sounds like a children's story, it's supposed to. Dallas wanted to make a game that would "surprise" players and make them feel "awe" and "wonder". The mechanics, if you will, of children's literature directly inspired the design of the game.

"That feeling of exploration and discovery," he says. "What is it about the physical experience of reading a children's book that works? Size. They're small, and when you're flipping through them, you know how far you are into a story. It's a different approach to a 500-page novel.

"There are great games that feel like 500-page novels," he quickly adds. "But we wanted to make something with a sense of wonder that is antithetical to that."

That sense of surprise begins with the very first playable moment of the game, in a completely white room. It is only when the correct button is pressed, and the first ball of paint cast out, that the world begins to take shape.

"We try to be very minimal in what we show to the players so they feel like they're discovering it for themselves," says Dallas. I watch a demo of the first section, which gently introduces the themes and structure.

You can be super-OCD about it and splatter every pixel until it's black, but then you'll have the exact same navigational problem in negative. Sound design, therefore, is a key piece of the puzzle.

Indeed, audio cues have been created in such a way that it is possible to "get through the whole space without looking at the screen", says Dallas - stressing that it's possible rather than the point.

Different sound properties and reverb effects for objects mean the player can deduce how wide an area is without looking, for instance. Rather like fascinating iOS title The Nightjar - which Dallas isn't familiar with - it can also be, he says, "a simulation of what it's like to be blind".

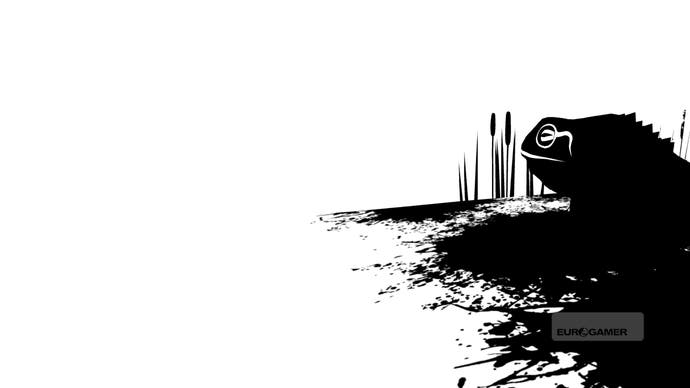

The only section of the game Giant Sparrow is showing is a simple navigational exercise to highlight the basics. Paint catches a frog as it leaps across Monroe's path; the ripples of water on a pool; a creature as it leaps above the surface, swallows another, and dives back beneath.

After a short while, more swan footprints appear as a guide. This is an example of just how iterative the development has needed to be in a project that began as a vague idea rather than a painstakingly mapped-out design.

The footsteps weren't there originally. But Dallas realised how quickly the player's uncertainty could turn to frustration. "If you don't give players any context, it's interesting for a minute but then their attention starts to wander."

The story itself is revealed through short sequences unlocked by collecting letters littered around the environment. The world has been created by a king with a magic paintbrush, with each area "a time capsule of what he was interested in at a different time", says Dallas.

He's being deliberately vague because he doesn't want to spoil it for me or you. All I'm told is that the rest of the game may pan out very differently from what I'm seeing here. The only nugget he lets slip: "There's more than one mechanic in the game, but they feed of same central idea of spatial exploration."

Charming, fascinating and fresh, it's still hard to know what to make of The Unfinished Swan while it remains a PR cygnet. And that's central to its appeal.

"In a way our game is almost like an extended tutorial," says Dallas. "The part of the game that to me as a player I often find most interesting is when I'm first learning how to do things.

"A lot of games can't wait to tell you everything they have that you can do. As a player I would much prefer to discover that on my own. So that's kind of what this game is: it's supposed to be all about discovering the game mechanics, and then the world as well, and in order to do that we needed to mix things up.

"So the approach we took was, maybe it's no longer about paint at all, maybe it's this totally new thing and we take what players have learned in terms of moving around the world and throwing the paint and go in a totally different direction from that."

In a world where every last feature and detail of a game is tiresomely drip-fed by publishers in limitless cut-and-paste press releases up to the day of release (and, yes, breathlessly reported by us hacks - we're part of the problem), it's heartening to see a major publisher just letting an idea breathe for a change.

It's a tough marketing conundrum for Sony in terms of how on earth it sells it to the public, but the great success of Journey both justifies the Santa Monica studio's laudable support for the weird and wonderful and provides a blueprint for how to hype a game without ruining it.

Once again, it all comes down to timing. "If you'd made a game like Journey five years ago, even if it was exactly the same game, it would be hard to find a place for people to want to do that," suggests Dallas.

"Now there's enough ground that's been broken that people are willing to, in the case of Fez for example, spend five years of your life making something and have a hope that you might actually find an audience and not just make a free Flash game out of it - which ten years ago might have been your only option. It's a great time for indie developers."

I can't tell you how his game will finish up. But colour me interested.