The Untouchables brought ragtime and ultraviolence to 8-bit

Naughty but Ness.

When film scholars talk about the magic of cinema, you increasingly wonder if they mean being hit by a Skyrim Vampiric Drain spell. There is nothing enchanting about the fiddly process of online booking, of navigating the drab corridors of a 13-screen multiplex, of breathing in the aroma of foot-long hot dogs apparently doomed to stew on heated rollers for eternity. Even if you manage to find your allocated seat among the choppy, often chippy sea of humanity, there's a deafening prelude of crass house ads, spoiler-filled trailers and Kevin Bacon hawking 4G before the magic can even begin - and that's usually the exact moment someone opens a gigantic bag of crisps.

Going to the cinema is borderline unbearable, then, but millions of us still do it because even with all the joy-sapping obstructions, there remains something uncanny about a movie - it's reality, and then some. We usually experience the world in a way that feels like a read-only file. But on that enormous screen, it's possible to witness a world that seems disturbingly real that is also bending to a creator's will. Using camera movement, editing and shot composition, this intense hyper-reality can be sculpted, shaped, even shredded. It might not technically be magic, but it's a really great trick.

That's why movies stay with us. Everyone has a personal canon of films that have been in their brain forever. In the years before Timehop and Letterboxd, you might not even remember when or where you first them, but Lady and the Tramp, E.T: The Extra-Terrestrial or An American Werewolf In London are so deeply ingrained, they're part of your firmware. Things only get confusing in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Ocean Software were licensing major Hollywood action films willy-nilly, then enthusiastically marketing their game tie-ins to consumers who were often too young to go and see the actual movie. In these cases, the experiences of game and movie sometimes become so entwined that it's impossible to separate the different memories.

For good or ill, I'm part of a generation that can't think of Terminator 2: Judgement Day without picturing Arnie's ruined robot face recast as a sliding block puzzle. In some extreme cases, playing the adaptation could put you off seeing the film forever (anyone who got Nightbreed: The Action Game bundled in with their Amiga is unlikely to be ordering the recent director's cut Blu-Ray). But mostly, the overlapping associations complement each other. Total Recall puts me in mind of a cute, chunky Arnie clodding about, entirely in keeping with Verhoeven's vision, while thinking of RoboCop makes me wonder whether they should have had more chainsaw-wielding maniacs in the film, even though they were an absolute pain to get past in the game.

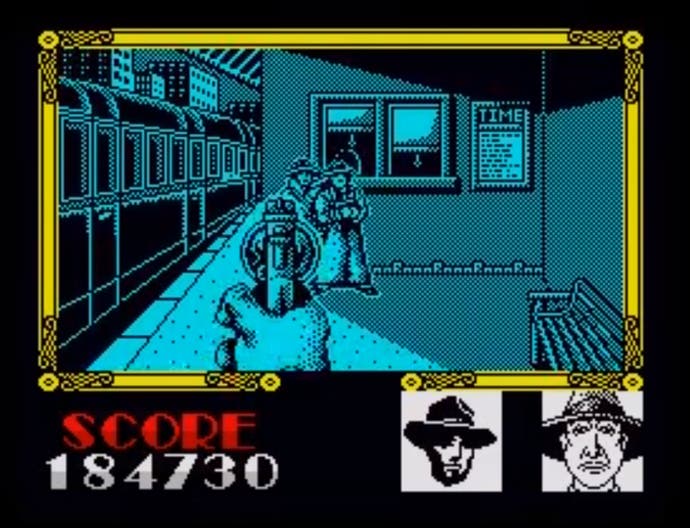

The Untouchables, which arrived on 8-bit and 16-bit almost two years after Brian De Palma's 1987 movie had been a sizeable critical and commercial hit, felt marvellous at the time: an expansive, polished Prohibition-era shoot-em-up that offered up six relatively distinct mini-games. Thankfully, none of them involved completing a sliding block puzzle of Sean Connery's scowling face as Irish beat cop Malone, although many included the illicit thrill of a bootleg liquor gauge, even if your dogged G-Man was mostly destroying the booze rather than imbibing it. My experience on the Spectrum should have been the most lo-fi of all the home computer versions, but it somehow seemed like the classiest - enviably crisp sprites rendered in a consistent palette of black and cool blue, accompanied by a series of digitised mugshots that kinda, sorta looked like at least some of the actors.

Intentionally or not, The Untouchables was also a system-seller, as the downside of having six completely different levels was having to load almost every single one of them separately. Ownership or access to a disk-drive-enabled Spectrum +3 was absolutely essential for maximum enjoyment. On old-fashioned cassette, the tussle for Chicago supremacy between Eliot Ness and Al Capone became a downtime-punctuated crawl. To exacerbate matters, the first level was actually the worst - a platform scramble round an anonymous warehouse, with you as Kevin Costner's dourly single-minded Ness, tasked with gathering evidence against the notorious crime boss through the time-honoured process of wasting gangsters, hopping between precariously-stacked pallets and picking up violin cases to access a Thompson sub-machine gun.

Even Ocean must have suspected that floaty platforming didn't showcase their game at its best, as they widely released the second level as a demo instead. This turned out to be a masterstroke, because that instalment - based on a bootlegger shoot-out on a bridge at the Canadian border - is the best of the lot. In the spirit of the arcade game Cabal, it's a thrilling shooting gallery where your character is also visible on-screen, rolling across the ground while firing off rifle rounds and destroying hooch barrels. A separate binocular scope nominally shows where you're aiming, but it's pretty easy to gauge from the trail of dustclod ricochets and trenchcoat-wrapped bodies you leave in your trigger-happy wake.

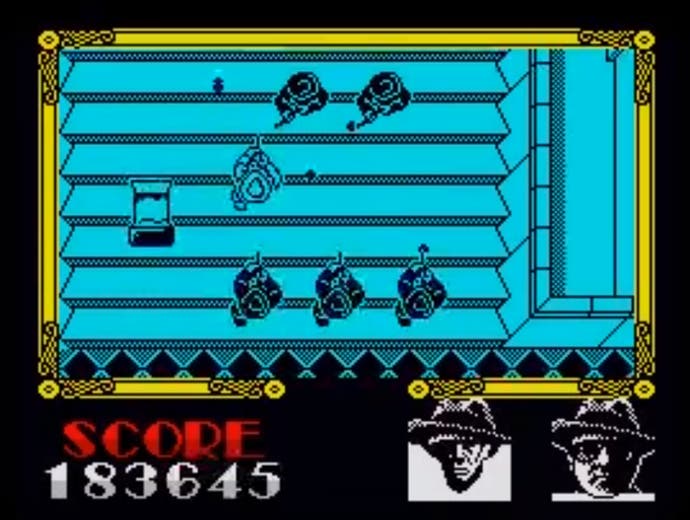

The third level, where you heft a shotgun in a tense alleyway shootout and swap between your four Untouchables to keep the mission-vital ones alive, is almost as good. But it's level four - where the action switches from side-on to top-down - that is especially memorable, as it recreates the most iconic scene in the movie, a haphazard shootout at a railway station that takes place while a baby's pram bumps through the crossfire. It was De Palma's celebrated, agonisingly drawn-out tribute to the Odessa Steps massacre in the silent movie classic Battleship Potemkin.

Just as BDP atomised and expanded what must have been a pretty sparse page of script - there's no dialogue, apart from a mimed scream of "my baby!" from the panicking mother - so the game extends it even further, charging you with managing the health of both Ness and the baby. Admittedly, it's another shooting gallery, albeit one that gives you the morally questionable option to use the pram as a temporary shield, safe in the knowledge that you can subsequently hustle it toward a restorative first-aid kit at the next landing. But 25 years on, another thought occurs: did The Untouchables accidentally invent the dreaded escort mission?

In the movie, the sharp suits for gangsters and G-Men alike were designed by Giorgio Armani. The score was just as lavish and lovingly tailored: a sumptuous, thrilling, Oscar-nominated suite by Ennio Morricone, It's unclear whether Ocean ever had the option to try and recreate the work of the Italian master, although 8-bit sound chips would certainly have struggled to recreate the querulous mouth organ and slightly detuned piano that characterise his soundtrack.

Instead, they opted for a very different but ultimately inspired route. Jonathan Dunn, Ocean's astonishingly talented in-house maestro, adapted the chirpy rags of Scott Joplin, imbuing the game with a bouncy, cheery energy that - while slightly at odds with the demands of mowing down dozens of wise guys - gives it an undeniable vim and vigour. It may have triggered a little cognitive dissonance in historians and cinephiles - ragtime was on its way out by the time Prohibition kicked in, and the syncopated style was also indelibly associated with The Sting, another sharply-tailored period piece - but it undeniably helped synthesise a cohesive identity for a potshot-pourri of a game. Deployed alongside the uniform colour scheme, it helped bind the disparate levels together, and make The Untouchables one of the most aesthetically successful video game movie adaptations of all time. If only the same could be said of Ocean's adaptation of that other Kevin Costner movie classic Waterworld - but that's another story.