The Video Game City Week: on the vivid authenticity of Midgar's slums

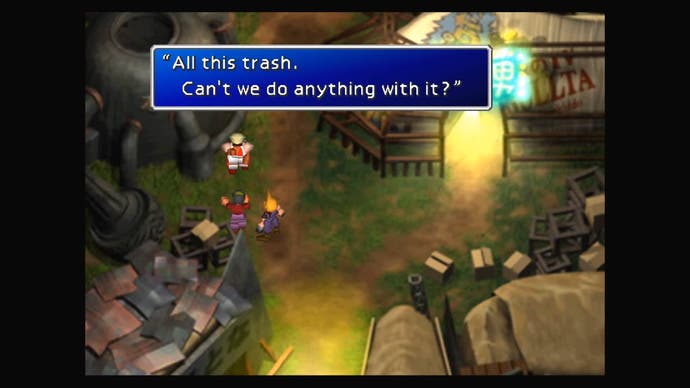

Bricolage.

Welcome back to The Video Game City Week. Next up, a visit to some familiar slums.

Midgar's slums

I often think about the playful, deceptively mundane poetry in the word ‘skyscraper’; a building so tall, so gross, that it can wound the skyline. Midgar’s slums have no real sky. And yet, in their vivid authenticity, stand taller than the places above them. Shops and houses hewn from a hodgepodge of discarded industrial scrap, made warm with smatterings of personal effects. Inside giant pipes, abandoned vehicles, and steel shacks, the people of the slums live and work. Midgar isn’t the only video game city to craft class division into its spatial topography, subterrain to skyscraper, but it’s the one that sticks with me as the most effective: a depiction of a marginalised class refashioning their segmented, stingy share of a city, turning a disused space into a physical extension of struggle, ingenuity, and resolve.

In the visual arts, the word bricolage refers to works made from recycled or disparate materials. It’s French, essentially meaning DIY, which means it’s also a loanword to english. I find this nerdily satisfying, since the word itself refers to a kind of syncretism. Midgar’s slums are an act of transformation born more immediately of necessity than defiance or self expression, for shelter and safety, for self-sufficiency. But the defiance comes through in its style, in its refusal not to be beautiful as well as functional. A more adherent cyberpunk setting would pull this off through patches and studs, bulletproof vests under aluminium-sheened puffer jackets. The residents of the slums do it with plant pots and tin patchwork, with girders and bulkheads, all reclaimed and reshaped into a distinct aesthetic identity. After all, you can spray “Fuck the Man” on all the tenement walls you want, but they’re still his walls.

Midgar as we know it in Final Fantasy 7 was originally several smaller settlements, before being gathered and reformed into metropolitan uniformity by Shinra. Midgar’s plate blots out not only the sun, but the shared cultural identity of its inhabitants, subsuming them into the rushing tide that power the water wheels of its destructive industry. Their futures halted, they shape fresh tommorows through a syncretic reclamation of that same industry. It brings to mind a subversion of the way ancient artefacts ‘acquired’ from overseas and locked up in the British Museum strips those artefacts of authentic context and freezes them as spectacle; the slum’s repurposing of ahistorical, acultural industrial layoff into useful spaces for living is a meaningful, if quiet, revolution against the theft of their own futures.

For me, the perfect video game city needs to show not only the social stratification that is sadly, but inevitably, part of any authentic metropolitan environment, but the ways these communities can reshape the space afforded to them, with the materials available to them, to better represent who they are as people. In architecture, bricolage refers to the effect of buildings from different periods and styles in proximity to each other, either incidentally or to evoke a deliberate post-modern muddle. In Midgar, you’ll occasionally find a greco-roman pillar scattered among the detritus. Ancient ruins, or discarded casino props? Neither would seem out of place, non-place as the city is. Time, then, to gather the remains of stolen futures, and build something new.