The week I went to Art Sqool

Brushing up.

I had a friend once whose father was an artist. He had a gallery for a bit, and had done a stark, mesmerising painting of a tiger that my friend hung in his living room. I close my eyes and I can still see that tiger, the paint piled up thick on the fur, the frightening energy of a beast frozen in movement, one paw raised, eyes fixed on the rest of us, that bland and deadly tiger confidence purring deep inside. "Did your dad like William Blake?" I asked. "YES!" said my friend. "It's that tiger! How did you know?" How could you not know? That's art I guess.

His dad had gone to art school in the fifties. Back then, I remember my friend explaining, for the first few weeks of art school you learned how to draw a circle. "Just a circle?" I asked, but there was no just about it. You had to learn how to draw a circle freehand. The circle had to be perfect. It took weeks. This was the foundation. Art school, I learned, back in the fifties, seemed whimsical, but when you tried the whimsy out for yourself with a pad and pen, you discovered it was actually a sheer form of rigour.

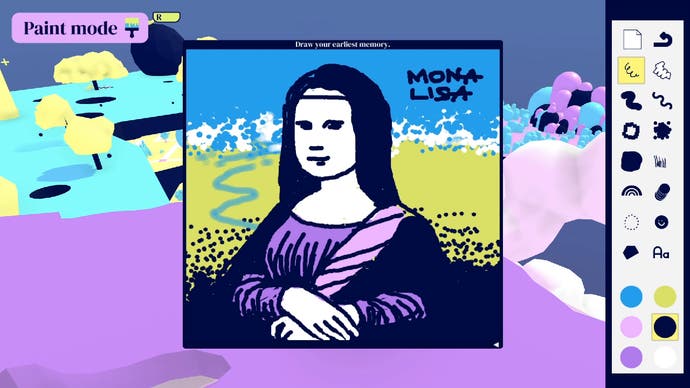

That's art school, then. But what about Art Sqool, which I have been attending for the last few days? Art Sqool is a game by the artist Julian Glander that has been out on PC and Mac for a few years, but which has just found its perfect home on the Switch. In Art Sqool you go to Art Sqool. Your teacher is a neural network. There are projects. You wander a campus. All that's missing really are those huge folders art students carry around that seem to act like rudders whenever it's windy out.

Listen: for a while, I felt slightly ashamed at how much fun I was having with Art Sqool. Slightly ashamed because somewhere, deep down, I mistook Art Sqool's breezy fun for a sort of archness. Arch Sqool. Was this secretly a game taking the piss out of the idea of art school, and by enjoying it I was one of those bourgeois clowns who doesn't know when he's being made fun of? Then I reckoned: does that actually matter? Honestly: I am a bourgeois clown already. I'm having fun here, let's just go with it. Then I had more fun. Then I read a brilliant piece by Emily Gosling that revealed Glander really did just want people to enjoy themselves and create stuff, so I felt dimly ashamed for having doubted him. Then I had a donut for lunch and felt better.

There is something of the donut to this game anyway. Something of the donut, something of that beautiful curly Q inserted into the word 'school' where it seems so mischievous. It is noodles with a donut chaser. Everything in Art Sqool is curved and rounded and glossy and perhaps glazed in strawberry. This is a campus I would eat. Speaking of things I would eat, early on I discovered an art brush to use called a rainbow brush. It basically creates tubular marshmallows of shifting colours: art that I would happily squirt straight into my mouth.

That campus, though! Art Sqool is pretty easy to get your head around. One by one, you are given a range of art projects by the neural network, and then you are left alone to wander the campus and collect brushes and whatnot and then have a go at the current project when you feel up to it. The campus is a delight: a series of floating dioramas strung amongst the clouds. The colours are the colours beloved of early home computer games - pale yellows and tart purples and hazy blues. There are swamps and climbing frames and upside-down buildings and sculptures that are almost definitely art in-jokes. At one point I came across a sort of out-door theatre with a huge projection screen. At another a tiny building had a table and a chair on top.

It's surreal but filled with the suggestion of mysterious utility. Which means it's a bit like wandering a university campus really. You understand your bit of the university, but the rest of it is just so...strange and wonderful. Bewildering.

I have spent hours here, wandering with my pad and pen, huge cartoon eyes staring at everything. Funny bushes, rabbits made of wire, big squiggly things on plinths. And then those projects! Draw an egg hatching - what's coming out of it? Draw the last person you said 'I love you' to. Draw an extremely technical patent diagram of an air conditioner. Astonishingly I got an A for that one.

Projects are marked by the neural network. Colour, composition, linework and approach. I love how random it is - again, a bit like university marking! Maybe the value of a professor is often not what they say, but the fact that they get you at it in the first place. I drew an egg with an arm emerging from it and I got an F. I tried again and this time I drew an octopus coming out. Reader, I got an A. I smashed the technical patent of the air conditioner assignment with a sort of wireframe box with a bow-tie on the front. I have repeatedly failed to "draw music".

It's a mark of the game, I think, that I spend a lot of time thinking about how to tackle these projects. And it's another mark of the game that I eventually give up thinking and just mess around with the art tools. Think MS Paint from about 1992. These tools are wonderfully imprecise, even before you start unlocking some of the weirder brushes. They are helpfully imprecise, to be honest: their innate clutzishness combines with my innate clutzishness to ensure that every artwork is a surprise. The Switch's touchscreen is not brilliant and that probably helps. I think this would probably be very frustrating if you were actually good at art, but if you were actually good at art, why would you be at art sqool anyway?

More than anything I love the rhythm of Art Sqool. You get your project and you wander the campus and observe and think. This is art, I guess: the objective, but then the process, and the process is often about letting things percolate, letting happy accidents and coincidences occur.

And most of all studying the real world. Rigour, even here. Looking at it. Charles Schulz, who I think would love Art Sqool, once said that he was always drawing with his mind. He would be chatting to someone and in his head he would be sketching the way their clothes creased and bunched at their elbows, say. He said that to abstract things you had to really understand them first. And you have to look at things as much as you can, look greedily.

My friend, the one whose dad went to art school in the fifties, told me about a time he came home from school with a black eye. His dad was concerned, obviously, but then he got out his pens and paper. "Hold it there," he said, "tilt your head, get in the light." He started to sketch what he saw. "Just fascinating."