The year in apocalypse

Looking back on 2017's dystopias and end-of-the-world tales.

Among Rain World's best tricks is that it doesn't end with you. Fall afoul of the reptiles who coil and flop through its moulting, fungal catacombs and you'll be dragged to a crevice and swiftly guzzled. The restart prompt appears, but you're under no pressure to hit the button, and really, what's your hurry? Death is an opportunity to enjoy Joar Jakobsson's chiselled 16-bit aesthetic and the game's AI ecosystem at leisure, freed from the rat-race of its core mechanics.

Predators come and go from boltholes: depending on where you've copped it, you might even see them fight, tumbling through the muck in a writhing knot, coughing up bright bubbles of neon blood. Light drifts over backdrop layers, burnishing dead machinery and throwing the shadows of unseen structures across the view, an effect that rather uncannily places the environment behind the player, as though you were perched on a rail in the foreground. It's mesmerising and, given Rain World's difficulty, reassuring: where other game worlds turn on the player's motions and decisions, your participation here is never represented as essential. This grotty, inhuman reality was getting on just fine before you arrived, and however hard the rain may fall, it will continue long after you are gone.

Games are fond of ending the world or staging its total corruption, and 2017 has (appropriately enough) delivered a bumper crop of post-apocalyptic and dystopian fantasies - all thrillingly distinct, and each a commentary on or unwitting reflection of historical forces that threaten disaster in reality, from climate change to religious fanaticism. Some of them take a guilty pleasure in the idea. For a role-playing shooter like Destiny 2, the apocalypse continues to be wish-fulfilment for compulsive hoarders and gladiators, a return to a simpler, more permissive "heroic" era, steeped in the pomp and hubris of the Space Race and the work of venerated sci-fi illustrators like Syd Mead and Chesley Bonestell.

The events of the Destiny universe follow a Golden Age of human exploration and expansion, a legacy that endures chiefly in the shape of arcane weapons and armour. Given Bungie's extensive borrowing of motifs from NASA and the Soviet space programme, each to some degree a proxy of the military, this says something in passing about what we, too, risk passing on to our descendants - the ICBMs that sleep in silos across the globe, the undetonated bombs and landmines that strew countries like Somalia and Iraq. The game's ability to actually comment on all this is, as ever with Destiny, blunted by its obsession with earning mechanisms and equipment tiers: it is much more a weapons factory than a story about how weapons become legacies. But if you weary of Bungie's well-oiled acquisition loops, you can always play it against the grain, picking at the architecture and mulling over connections rather than grinding those drops, much as you can linger posthumously in Rain World to see what the simulation gets up to in your absence.

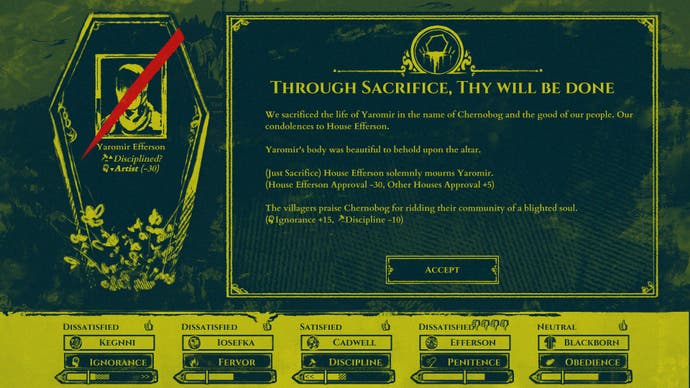

Kitfox's The Shrouded Isle also regards the apocalypse as a return to simpler times, a bloody and bureaucratic wiping of the slate. It puts you in charge of an island cult, tasked with preparing for the arrival of a death-god by weaselling out and sacrificing heretics, free-thinkers and anybody you think nobody would greatly miss. Stupidity is to be cultivated, spontaneity frowned upon, curiosity reviled, the urge to create stamped out. Among this very cynical tale's winning qualities is that the player's own ignorance becomes precious. Most of your victims are an even mix of vices and virtues, and it's important not to expose too much about the latter before you lay them on the altar, lest the other villagers rise against you.

It speaks to the doublethink integral to any absolutist ideology, the need to actively protect yourself from certain, infectious truths or perspectives, a feat that bizarrely involves recognising something of what it is you're trying desperately not to understand. This is also captured by the game's magnificently nasty character portraits, their eyes scraped away as though in self-mutilation, which arise from a design economy that chimes nastily with the story's sense of the cheapness of human life. As artist Erica June Lahaie has explained, eyeless characters are harder to distinguish, which makes the reuse of those assets from session to session less noticeable.

For Bloober Team's Observer, the end of the world is the end of a meaningful distinction between meatspace and cyberspace, or possibly the revelation that this distinction was always meaningless. It means scuffed brick and dank wallpaper that are sporadically swallowed up by a holographic haze, either generated by the building's advertising and surveillance fixtures, or inserted by your own, unreliable eye implants. It means prying open corpse brains like warheads to expose a range of contrasting playspaces, many confusingly overlapped, all of them raked by video noise and glitches (a tacit anthology structure that is intriguingly reminiscent of the rather sunnier What Remains Of Edith Finch). It means wandering through endless forests that are also grubby repairshops, and gazing up at cables that are also sinews and tendons.

There is little optimism and fellow feeling to squeeze from Observer's septic torso of an apartment block, but what moments of warmth the game does offer linger in the memory: helping a resident overcome a panic attack, for example, or gently unspooling the loneliness of a murderer who feels trapped in the wrong body. Part of the game's achievement is that detective protagonist Daniel Lazarski is of a kind with the ruined people he interrogates, granted a certain license but ultimately just another damaged thrall of the corporate state, kept obedient by a drug you must take constantly to stave off the degradation of your visual feed. In practice there are no real consequences for doing without your Synchrozine, but it's a powerful statement nonetheless of how the minds and bodies of the downtrodden may come to reflect the ruptures and discords that surround them.

Ether Interactive's LOCAL HOST is a great companion text. It, too, explores a dystopia in which flesh and tech feed into one another without seam, and broaches a revolutionary solidarity between machines and humans while probing at the construction of gender identity. Players assume the role of a contractor at a greasy tech lab who is ordered to unlock and wipe four hard drives, the difficulty being that the programs on those drives portray themselves as sentient. To do your job you must plug each drive into a beat-up robot body and "persuade" the AI either that it is time to die, or that it was never alive in the first place. As with Observer, LOCAL HOST is fundamentally a game about the possibility of empathy in a world that no longer has a social fabric, in which we are all bound together by capital and circuitry yet always alone. It's a smart, troubled exercise in acknowledging or refusing personhood that benefits from a canny script and some delicate visual flourishes. Each AI has its own body language and accompanying musical theme, and the sight of the robot's mouth gaping in shock as each construct loads never loses its chill.

For Dishonored: The Death of the Outsider, the apocalypse means the end of god - not just the loss of a key character, but of the game's primal scapegoat and structuring element, the black-eyed deity whose gifts animate every protagonist in the series and thus, give rise to each environment's intricate assemblage of routes and opportunities. Every Dishonored level ever made is at heart a conflict between the Outsider's ethic of transgression and self-determination and Gristol's various calcified monastic and aristocratic orders. The Church of the Everyman's Seven Strictures are an all-but-explicit denunciation of the game's own design "pillars", its patterns of exploration, infiltration and experimentation. Do not look, do not roam, do not trespass, do not steal, do not admit contrary thoughts; in short, do not acknowledge the existence of options.

This world's future is, like that of the franchise, uncertain, but turn your eyes upward while stalking a thug from corner to corner, and you might scry a certain hopefulness in the windmills that shadow Karnaca's plunging streets. The second game's introduction of renewable power is no mere cosmetic touch or show of topicality, but integral to its preoccupation with the links between ecological decrepitude, social malaise and sickness of the soul. Dishonored's quasi-Victorian archipelago remains dependent on whale oil for power, a profound desecration that tethers the realm's prosperity to the ocean's abused depths and thus, the seductive, treacherous, cetacean Void personified and contained by the Outsider. Those whirring, sunlit blades suggest a kind of freedom from that, energy and agency obtained without the immense spiritual cost.

In the event that Dishonored 3 does get made, of course, I doubt things will pan out that smoothly. Gristol is a society in which people are lobotomised for studying magic and gentlefolk literally get high on the blood of paupers: it's hard to imagine a hearty dose of renewables turning the place into an earthly paradise overnight. But it's a nice image to end on, and a reminder that post-apocalyptic and dystopian fictions are always, for all their extravagant bleakness, works of secret optimism. In reality the world is always ending, as generation gives way to generation, ideologies rise and fizzle out, unforeseen natural catastrophes take their toll and technologies displace one another. To tell stories about and after that end is, in itself, to insist on continuity and the chance - always the chance - of something better.