Tomb Raider: Underworld retrospective

How low can she go?

You can tell a lot about a videogame character from the way they climb a ledge.

Mario, for instance. He's a hyperactive, middle-aged toddler, hooking his leg around the ridge of a platform with the eager enthusiasm of a one-year-old clambering up the sofa all by himself for the first time. Nathan Drake meanwhile, with his amateurish swagger, heaves himself around with the kind of casual athleticism that derives from bravado as much as ability. But Lara, the old Lara, the Lara Croft of Tomb Raider: Underworld - she climbs ledges with style.

Pulling herself upward simply by the strength in her arms, Lara doesn't stop like Drake and Mario would when her waist is above ledge height. Instead, she keeps going, her limbs straightening and raising until she's perfectly, exquisitely balanced - her whole body extended perpendicular to the ground, upside down. Only then does she dismount, tipping her legs forward with masterful, gymnastic elegance until she lands, feet first, on the platform. This is Lara's handstand, her elegant spine-bending signature move.

Watching Lara in action is like watching expensive brandy flow into a glass. The handstand's the kind of pointless, gymnastic flourish that reminds us that Lara isn't some eager amateur but a trained, talented professional, at home in a world where tombs and cave systems are built from neat, straight lines. I like to think it hints at her privileged, aristocratic upbringing too - perhaps the young Lady Croft was treated to some private gymnastic tutoring along with all the roast swan and pony rides when she was a child? And there's no point denying that, for better or worse, it's a manoeuvre that's a little bit sexy. There's something faintly languorous about the way her legs drape downwards on the dismount, just as there's a pause to the fraction of a second she holds herself taut. No wonder it's a move that Eidos would frequently have their official Lara Croft models perform, much to the delight of the red tops.

But the genius of Lara's handstand actually derives from the fact it's entirely optional. Should Lara be hanging from a ledge and the player merely taps the jump button, she'll clamber upwards with tidy efficiency. It's holding jump that activates the handstand, that extra effort and deliberation to your input echoed and amplified by Lara's showing off in return. It's this blend of character conveyed through motion coupled with precise control that summed up the old Lara Croft, and it's at the heart of Tomb Raider Underworld.

Underworld is a game about descending, that tight control scheme coupled with level design that - true to the title - frequently sees Lara push further and further underground. Tomb Raider has always been a series about its environments as much as its star, but here Croft really is dwarfed by the vast, cavernous spaces she explores. It's hard to believe, given quite how long it's lasted, but Underworld is to date (Guardian Of Light aside) the only Tomb Raider game released to have been developed with this generation exclusively in mind, a brand new engine helping to give the crumbling mausoleums and ruined temples a rare sense of depth and scale. So much scale, in fact, that Lara had to be positioned hundreds of feet above them to properly take it in. Why else would Crystal Dynamics take the relatively risky manoeuvre of building the opening moments of its adventure (explosive prologue aside) around underwater controls?

Core Design cast Lara adrift once or twice, of course, but Underworld's underwater sections make Tomb Raider 2's 40 fathoms look like a splash in the shallow end of a paddling pool, as Lara floats in the ocean's yawning expanse and vast structures come murkily into view, begging to be explored. Neatly bookending the adventure, these two sequences are Underworld at its most majestic, letting players admire the scope of the tombs they'll be raiding before they're forced to ponder their intricacies. There's some basic lock-and-key puzzling to be done beneath the waves, of course, and small schools of sharks occasionally provide a more urgent distraction, but for the most part these underwater sections, despite the heavy presence in promotional material, were just the briny, scene-setting starters before the more conventional main course.

Inside Underworld's tombs, things still ran like, well, clockwork. There's a mechanical logic to Underworld's spaces that means that I can never believe in them as places, as fun as they are to explore: statues fall to pieces just as Lara's in need of a weight to depress a switch on the floor, chambers are ridged with handhelds that just happen to make up for their ruined stairs and almost every room will be studded with brass rings that - by gosh! - fit perfectly with her grappling hook. GLaDOS couldn't have come up with spaces this contrived, and she was working with a self-assembling, semi-automated testing facility.

But if there's a price to be paid in the form of suspension of disbelief, then players are treated to some wonderfully deliberate, acrobatic platforming in return. It's commonly accepted wisdom that Nathan Drake has supplanted Lara as gaming's adventurous-archaeologist-in-chief, but Uncharted's platforming is entirely different to the careful spelunking found in Underworld. Whereas Naughty Dogs's games offer clearly defined routes enlivened with desperate leaps and fumbling near-falls, Underworld is all about figuring out your path, and methodically working through it using Lara's supple, flexible move-set.

The grapple is the star here, a context-sensitive tool that seriously bolsters Lara's adventurer credentials. As well as being used for the swinging and wall-running seen in Legend and Anniversary, Underworld added the ability to rappel up and down walls. Obvious additions, maybe, but ones that introduced a greater sense of verticality in Underworld's level design. You're constantly descending through these dungeons, moving downwards rather than horizontally, and there's a quietly spine-tingling thrill to watching Lara dangle as she lowers herself into a dusty, long undisturbed chamber.

But if Crystal Dynamics perfected Lara's movement, they still failed to provide engaging combat, even if a generous lock-on ensures that killing things is more a distraction than a chore. In fact, there's a faintly apologetic feeling to Underworld's enemy encounters: monsters and mercenaries charge straight into to the path of Lara's bullets, seemingly as eager as you are to empty the room and let Lara explore.

Boring shooting is part of the Lara legacy, of course. And if the imminent reboot suggests that Crystal Dynamics was tired of working within the template they'd inherited, then I don't think it's too fanciful to suggest that the seeds of that malaise can be spotted here. Blowing up Croft Manor looks like a rather desperate move, with hindsight, an attempt to strike at the heart of a character who didn't actually have one. Old Lara was too cartoonish to care about, really, which is why killing off a member of her supporting cast was equally ineffective. It's easy to see the dialling up of Lara's vulnerability in the new game as symptomatic of ingrained sexism in narratives featuring female leads, but looking back, perhaps it's merely overcompensation.

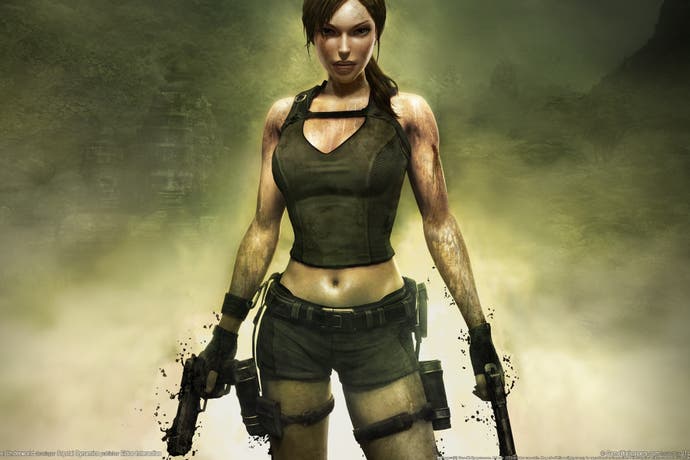

The biggest pieces of Lara baggage, of course, come as a pair. Lara's sex symbol status runs awkwardly throughout Underworld, a game that gave Lara a no-nonsense ponytail after years of plaits but then hurriedly stuffed her in wetsuit cut halfway up her arse. Clothes were a sticking point for Crystal Dynamics, it seems: each mission begins with you choosing Lara's outfit, and the choice is invariably between something sensible for the occasion and something that leaves a few extra inches of flesh bare. Plenty of games offer costume changes, but it's hard not to see this as indecisiveness of Crystal Dynamics' part, an awkward stepping-stone on the way to having Lara finally give up the hot pants.

It's funny really, that a game so concerned with ransacking temples for their long-forgotten treasures should itself so quickly become a relic. But that's what Underworld is, half a decade on from its release. It's throwback to a time when shooters had lock-on buttons, not cover systems; a time when platforming meant planning and deliberating, not scrabbling madly from one crumbling handhold to next. And it's a throwback to a time when Lady Lara Croft vaulted elegantly onto ledges, rather than dragging her bruised and battered frame across them.