Tomodachi Life review

A life less ordinary.

Where does the line between toy and game lie? You get the sense that with Nintendo it's never mattered too much, as evidenced by the chunky playfulness of its hardware - the DS was built to withstand a tumble from a child's bicycle basket - as well as the exuberance of its software. When you're revelling in the joyous arc of one of Mario Kart 8's drifts, or in the tactile bound of Mario himself, the line is gleefully blurred.

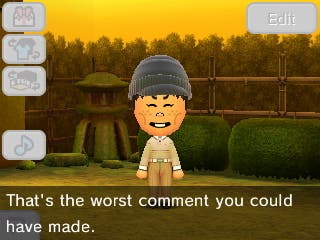

In Tomodachi Life, the 3DS life simulator making a belated outing in the west after a couple of successful series releases in Japan, that line comes more sharply into focus. It's an odd game - quite aggressively so - yet its excessive eccentricity isn't really enough to excuse how little room it leaves the player, and how boring it all quickly becomes.

The oddness shouldn't come as much of a surprise, since Tomodachi Life has emerged from Nintendo's SPD Group 1, the team behind the anarchic WarioWare series and a studio that stars Metroid creator Yoshio Sakimoto. The lack of interactivity, though, should. WarioWare's always been about deconstructing what it is to be a game, while Tomodachi Life goes out of its way to avoid every really becoming one.

You start off by taking your Mii, or more truthfully a Mii fashioned in your likeness, to an island full of hazy distractions, where there are parks to wander, cafés to idle away time in and fairground attractions to ride on. It's all held at arm's length, though, and you're never given direct control over any of the characters. Instead, it's a case of prodding them through menus, seeing to their wants and desires, and slowly populating the island with a cast of your own creation.

There's fun to be had in observing the island, for sure, and the quirky humour that's held together the rough-edged aesthetic of the WarioWare games makes for a likeable distraction for the first few hours. You're encouraged to put friends as well as celebrities in the apartment blocks of your island, which makes for some curious partnerships. I placed Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr together in the hope they'd hit it off and have a child, but he's become besotted with Princess Zelda while she spends her nights round Fernando Alonso's house, lost in starry-eyed conversation.

The incongruity of it all makes for a novelty that takes its time to dull: by night you can peer in on the inhabitants' strange dreams, while by day they'll pair up for rap battles by the fountain, meet for coffees and idle chats or simply roll around the floors of their apartments. You're never much more than a voyeur in any of this, though for a while you're a happily bemused one.

Islanders make friends with each other or perhaps even fall in love - and with a little encouragement here and there, they'll even get married, move in with each other and have children who are free to stay on the island or travel, via the wonder of StreetPass, further afar to inhabit other islands. They each have their own wants and desires and their own tastes: it's perfectly possible to dress each and every one of them in the style of your choosing, culled from one of the many shops around the island that are restocked on a daily basis, but there's no guarantee the set of rabbit ears you're so keen on won't set the islander off in a huff.

The thin thread that keeps you coming back is the happiness of your islanders, each of whom levels up the more attention you pay to them, while a simple star system reflects the well-being of the general populace. It's a thread that snaps all too quickly, though - keeping islanders happy is about nothing more than a succession of mini-games that quickly become repetitive, and simply throwing more stuff at them to numbly consume.

The grim economy soon chips away at the game's slightly forced grin, and the joy that once met each appearance of an islander soon becomes something a little less upbeat as they blithely seek more attention only to waste your time with another mini-game or to consume another meal. Tomodachi Life is different enough to Nintendo's other life simulator, Animal Crossing, to escape comparison, yet the company would still have done well to study how that series gently embeds itself in players' lives.

It's the lack of agency that ultimately works against the game, a fact starkly spelled out in the controversy that's eclipsed much of the run-up to Tomodachi Life's release. The inability to recognise same-sex relationships is a problem, yes, but it's just one of several in a world that leaves so very little room for the player, offering little by way of self-expression.

What's left is nothing more than a novelty, albeit one that's perfectly captivating while you're under its spell. The abundance of surreal moments - when you chance across Shigeru Miyamoto singing to himself in the bath, or when a news flash shows you Raymond Carver sliding down the neck of a giraffe named after Alonso - make for a game that's fun to tell others about, but dull to play. Like Yoot Saito's strange Dreamcast virtual pet game Seaman, Tomodachi Life is deservedly destined for cult status - but as anyone who spent long, lonely nights trying without success to get a depressive fish to understand their simple commands will attest, that doesn't necessarily make it hold together as a compelling game.

Tomodachi Life is a simple, throwaway toy, then - one with plenty of cute tricks, but not quite enough of them to stop you from tossing it aside after a handful of hours. There's no shame in that, of course - especially from a company that's excelled in novelty ever since Gunpei Yokoi's Love Tester, a device obliquely referenced in the metrics that measure the compatibility and chemistry between each of your islanders. Yet despite its exuberance and eccentricity, it's hard to recommend a life simulator with no real sense of simulation, and very little in the way of life.