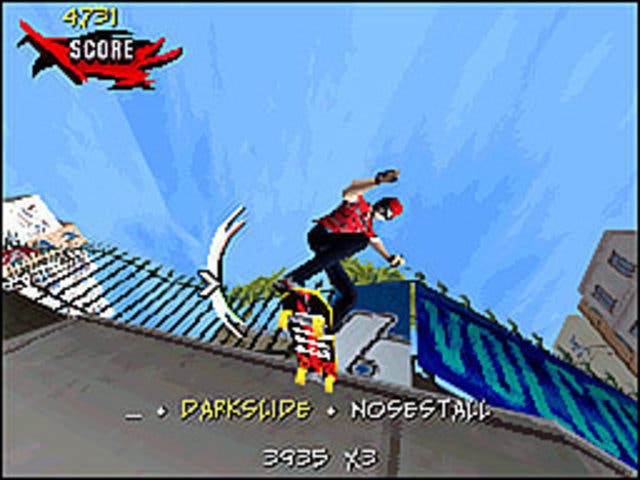

Tony Hawk's Motion review

He likes to move it move it.

Motion! It's the buzzword of this gaming generation, bringing with it the unspoken assumption that any game can be made better by incorporating a cheeky bit of waggle. Utter nonsense, of course, but with the Wii still hurtling off the shelves it's easy to see why a publisher might jump on the motion-sensing bandwagon.

Tony Hawk's Motion, as the name suggests, attempts to apply the brave new world of tilt and twist to the evergreen extreme sports genre, and on the DS no less. It does this by virtue of a little plastic dongle that fits snugly into the GBA port, which then allows the DS to tell if it's being wobbled around. At least until the DSi comes out.

So how does this affect the world of Tony Hawk? Badly, is the unsurprising answer. Unlike Shaun White Snowboarding on the Wii balance board, there's no tactile connection between tilting a DS and riding a skateboard, so you're simply tipping the console to turn left or right, while still using every other face button to pull off tricks. It doesn't feel any more like skateboarding (or snowboarding, the other sport in the game) than pressing a d-pad, and it brings with it some rather obvious drawbacks.

Chief among these is the simple fact that when you tilt your DS, you're tilting the screen as well. You can either play blind, or move your head around as well to keep the game in view. Both options stick a knife in the playability, and this alone should suggest that motion sensing in a handheld is always going to have limited uses.

Using a game like Tony Hawk to showcase the motion technology therefore seems like a perverse choice, given that skateboarding sims are fairly complex to control at the best of times, and tend to require precision movements to boot. Assuming you can steer your boarder while keeping the screen in view, simply landing a grind can be a right fuss and it's not as if mastering the floaty movement brings with it any kind of gameplay reward. To paraphrase the great philosopher Jeff Goldblum, it feels like Activision's scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should.

It's not even as if the game itself is all that fulfilling. You start with just two locations - one for snowboarding, one for skating - and each contains a handful of mini-games, ranging from simple score attacks to slaloms and following lines of green dots. There doesn't seem to be any stringent criteria for success, since I managed to unlock the second skating arena in Tokyo while pootling about trying to get a handle on the controls. A similarly half-hearted exploration of the snowboarding side of things unlocked the final quarter of game content. Yes, there are only four small stages and you can access them all within about ten minutes. Awesome.

But that's not all! Making up the second half of this bizarre package is Hue Pixel Painter, another motion-based effort that has absolutely nothing in common with Tony Hawk. In this one you guide an anthropomorphic paintbrush around flat, monochrome scenes by tilting the DS. Double-jumping on cracks in the ground creates a geyser of paint, which you can then use to paint lines between different pools of colour. Doing so invigorates whatever scenery you've managed to box in.

And...well, that's it. There are a few more stages, some enemies to complicate matters slightly, but it's even thinner than the sporting half of the package. It's a cute idea, in theory, and could even have made for a fun puzzle game with a bit more development, but in this form it's barely half a game.

Since you can pretty much exhaust the available gameplay within half an hour of switching the DS on, it seems likely that this curiously half-baked compilation was simply a way for Activision to use the Tony Hawk brand to get their motion sensing peripheral into the market. Yet so flimsy are the games that it feels like they simply bundled the internal tech demos designed to test the hardware and dressed it up as a commercial game.