Touch Tone exposes the strange landscape of Spook Country

Locked up in PRISM.

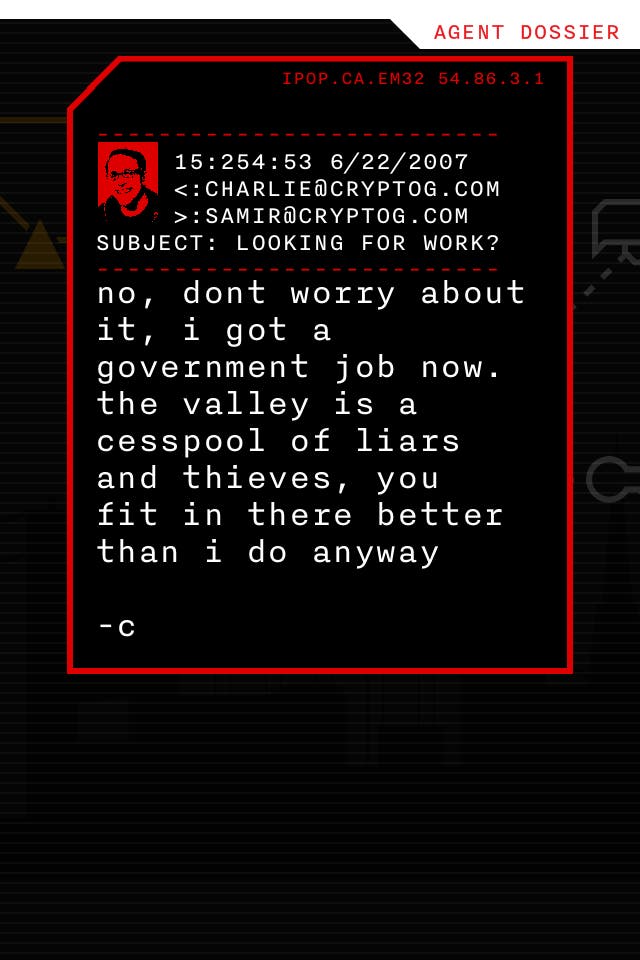

Samir Jilani: smart, Iranian and a Muslim. According to the security service depicted in Touch Tone, that's practically an admission of guilt. It's definitely reason enough to start reading his private emails and texts. I should know. I'm the one who's been reading them.

Touch Tone is a puzzle game about abusing other people's privacy, and its tutorial teaches you a lot more than just how the puzzles work. It teaches you about the, well, tone of the whole thing: the skewed reality its unfolding narrative will drop you into. It does this by setting you a few simple tester tasks. Hack a few messages. Read them. Now, which of them is worthy of future investigation?

Here are a couple of Wall Street types dealing in dodgy bonds. Post 2008, I took a pretty dim view of this, and so I flagged it for the feds. Wrong answer, says Touch Tone: Wall Street types are just doing their thing. It's the economy, stupid. Keep moving.

Next up. Here are some high school kids trying to score some pot. No big deal, I figure: schoolyard wasters just doing their thing. I wonder what they've painted on the side of their van. Wrong again, says Touch Tone. Drugs today, but what's next? Terrorism? Very possibly. This one is a big deal.

Touch Tone would be satire so heavy-handed and implausible that it might carry no sting - if only we didn't live in a world that's even more heavy-handed and implausible. It feels particularly apt to play Touch Tone over the weekend in which John Oliver asked Edward Snowden if he misses Hot Pockets now that he's living in Moscow, wanted by his own government. With Neon Struct on the horizon and Touch Tone on the iPhone, it strikes me that video games have not been slow to react to Snowden. Probably because, if you're inside the world of video games, he might feel like one of us. Smarter and braver - or devious and more reckless, depending on your politics - but undeniably a member of the gang, a child of internet forums and touchscreens, who changed the world with a USB drive rather than a manifesto or a handgun.

Snowden's everywhere in Touch Tone, since it's a game about dealing with very clever people in a pretty stupid way. But hey, Jilani had it coming, right? He's trying to raise money for his encryption startup in Silicon Valley - aren't we all - and when an investor tells him to dump his existing partner, we discover, a few messages later, that he did just that. His girlfriend goes nuts, of course - we're a few messages on once again - but what right has she got to preach about faithfulness? That's us talking, not Jilani, and the reason we can ask is because we've been reading her messages and we know she had an affair a while back.

Everybody is complicit in something in Touch Tone: everybody is guilty. This is probably how security services start to see the people they snoop on, which is all of us, rather worryingly. It's definitely how they justify the snooping. The most complicit person in Touch Tone, though, the most compromised, to use security speak, is the player, who gets to read the emails and messages of perfect strangers for no very good reason. You may tut to yourself about how wrong it is, but when the next message pops up, how quickly do you click on it to tap, once more, into the soap opera of life?

This is the meat of the game, I think: an experiment in being someone else, in doing something uniquely, topically terrible. What would normally be the meat of a game like this, however, lies elsewhere, on a neat vector grid as you solve spatial puzzles to unlock Jilani's messages.

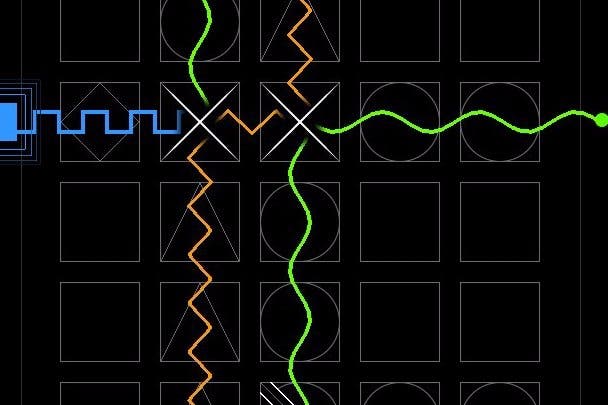

Touch Tone is essentially a suite of hacking challenges in which you move mirrors, reflectors, and splitters around to bounce different coloured beams to their different coloured targets. It ramps up quickly in terms of complexity, and yet it never lapses into noise. There's always a neat twist to a puzzle, a clever shape created by the placement of mirrors when the solution is finally reached. The rows and columns work like conveyor belts, which means that if you move one mirror, you move everything else in the row and column it's in. This adds another layer of delicacy. If the first puzzle is working out where to put stuff, the second is working out how to get it there.

Throughout all this, there is a lovely bit of balancing in place. Touch Tone fails if the puzzles are a trudge, but it also fails if they become so engrossing that you care about them more than the snippets of story they're unlocking. For the most part, they're a pleasant way to get to the dark treats you're really after. They are fun to complete, but they don't let you off the hook: you're playing to snoop more into Jilani's world and you can't pretend otherwise.

I am still early on in this, and I have no idea if there are cases lurking beyond Jilani's. I have no idea whether his encryption software is the real lure for the feds, or if he'll end up in Santa Monica or GTMO because of what I'm doing. I feel involved, though: a stupid part of a wilfully stupid machine.

Mikengreg, the developer that has made Touch Tone, once created Solipskier, one of the great apps of all time in which you race through an imaginary landscape shut off from the world by your speed and your giant headphones. A cocoon of sheer privacy. Less than a decade later, it's trickier to believe in that: in privacy, in self-sufficiency. In Touch Tone, we are never alone, and we are always connected.