Town of Light review

It's Bedlam in here.

"When you're mad, you cease to exist."

The Town of Light is a game set in an asylum, and several decades of games like it have taught us what those words mean. Spookiness. Evil experiments. Something sinister in the basement. Jump-scares. This doesn't have any of that, but don't for a moment think that means it's not a horror game. Its horrors are simply more grounded, in incarceration, in loneliness, in the loss of power, and complete subjugation by a system that, at best, sees you as an unperson incapable of not simply making your own decisions, but of holding your own world inside your head.

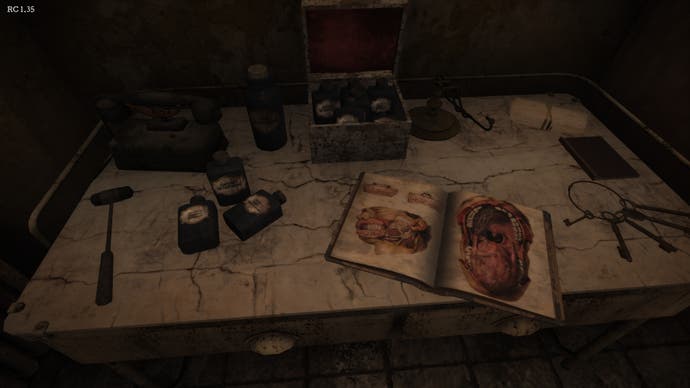

It's the story of a young girl called Renee, committed to an Italian asylum shortly before World War 2, as she explores its ruined, dilapidated hallways decades in the future. It's based on a real location, and while it's not as complex as many game spaces out there, The Town of Light does a fantastic job of rebuilding it in all its rusted over, graffiti-covered glory. Every room hangs heavy with history, haunted not by ghosts in the conventional sense, but certainly a lingering misery that suffuses every bit of brick and every bed fitted with thick leather straps.

This is not a fun experience, and oddly, what makes it worse is that for every moment of genuine sickness on display, there's another marked primarily by banality, or even well-meaning cruelty done in the name of efficiency and the self-assurance of knowing better. What makes it worse is that often, this is probably accurate. Renee is the ultimate unreliable narrator, her calm and generally rational, if somewhat on-the-nose narration at extreme odds with what we read about her stay, and her perception often run through with memory lapses and hallucination. The staff of the asylum do not come out of this well, but The Town of Light resists the cheap drama of simply making them all sadists. Some are simply doing the best they can with limited information, believing in electroshock and similar as miracle cures. Others, as even the game points out, are simply buried by their workloads, especially once World War 2 breaks out.

I'm not going to call this a 'walking simulator', because that stupid phrase should be fired into the sun. This is very much a narrative experience though, gently guiding you from scene to scene on a three-hour or so journey into Renee's mind and past - the ruins often flashing back to strong, brightly lit monochrome version of the asylum while it was fully operational. Light is the enemy here, burning the screen with its presence and making the shadows all the more sinister. Again, there's no jump-scares, but there are a lot of quick fades to hand-drawn versions of rooms full of sinister faces, of faceless nurses, of battered monochrome flesh and sobbing eyes.

Early on especially, the interactive elements let the side down badly. You can't explore the asylum at will, or at least, not early on - and the story only progresses when you go to the next place on the guided tour of Renee's personal hell. Only a few objects can be picked up and examined though, and a few notes, all of them relating to her, despite the space crying out for more exploration and more detail. Progress is then not based on anything direct, but doing largely random things like putting a doll into a wheelchair so that it can then be put under some hot lamps and not feel cold so that the next door will open. It's not a puzzle, the game tells you what to do, but there doesn't seem any good reason why it can't let you off the leash.

As things go on though, this ceases to be an issue. The narrative flow of the story is very careful and considered, and while a little more freedom would have been nice at times, it soon becomes clear that the real purpose for it isn't choice, but providing a measure of complicity. A guard disappearing with Renee's doll/only friend. You follow, because you have to follow. You realise you're being led towards the bathrooms, with the right sick sense of knowing exactly what's going on, but being utterly powerless to do anything about it but be dragged along. Likewise, later in a shower scene, you remove your clothes to take your shower because that is the only action that can be done. You deliberately have no more control over it than Renee does, and yet for that moment it's a joyful thing because it promises a rare moment of happiness.

It doesn't last, of course. Many of the scenes lead to deeply, deeply unpleasant scenes, most of them depicted graphically with pencil drawings. Rape, torture, a moment's happiness being physically torn away, the throttling of inner demons made manifest by nightmare. It's to The Town of Light's credit that it neither comes across as trying to shock, nor ever pulls back from unpleasant or simply uncomfortable scenes, like the asylum's patients queuing up for their shower. It simply presents them, compassionate, but deliberately cold, dehumanising and miserable, where the true misery doesn't come from the moment, but the promise that it will never, ever end. What initially seems a relatively linear tale also soon loops back in on itself, often adding at least some internal justification for what often first seemed callous acts of cruelty or apathy. Which is not to say they make them or the inevitable results any better.

This is, in short, not an easy three or so hours to get through. From the lingering sexual abuse side to a truly hard to watch ending, The Town of Light has no interest in making it easy. Amongst many other twists of the knife, Renee is only sixteen when the game starts, and the passing of time is the least of what ages her as the story progresses. By the time we begin, as the titles roll, the asylum is being knocked down, repainted, and that tale - just one of many, not even that special - being washed away and so easily forgotten. Her story... ultimately... doesn't matter. That renders some games pointless. Here, it's just one more twist of the knife.

What does drag against the experience more than it helps though is Renee's internal monologue, which works too hard to vocalise what the individual scenes have done more effectively, and is often over-written to the point of losing what power it has left. Its style makes a certain sense, including the moments where you act as the voice in her head as she tries to piece things together, but more than once I heard Futurama's Robot Devil in my own, declaring "You can't just have your characters announce how they feel! That makes me feel angry!"

However, the nature of the story and the highs of its better moments make it hard not to be affected by what The Town of Light does. It's a far better exploration of mental issues than past attempts like Ether One and Sanitarium ever dreamed of being, and more specifically, the closest you ever want to be to this side of treatment. There's no conspiracy, no mystery, no oogie-boogie monster in the basement. The Town of Light is simply a slice of history that welcomes you into its halls to share your empathy, without locking the doors behind you.